January-March 2024

There was a guy named Maxwell, who was born on that day, 100 years ago, even if his birth certificate doesn’t say so. His second name was Lemuel. Whatever — everybody calls him Max. Let’s embark for a 100 days celebration with Max Roach, here on Mastodon. You know what to do? — Follow the hashtag…

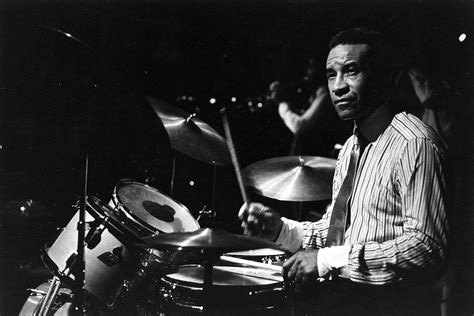

Today’s tune is a solo tune, recorded 1965, from the album Drums Unlimited. This tracks actually opens the album.

Yes, it’s a waltz, and yes, it’s music, and yes, it’s drums!

“The Drum Also Waltzes”, Drums Unlimited, 1966

The melody starts very simply, with a waltz groove sustained by Roach’s hi-hat that plays regularly on the second beat of each 3/4 bar. Tension grows to a dense part, and the music goes back to the initial theme.

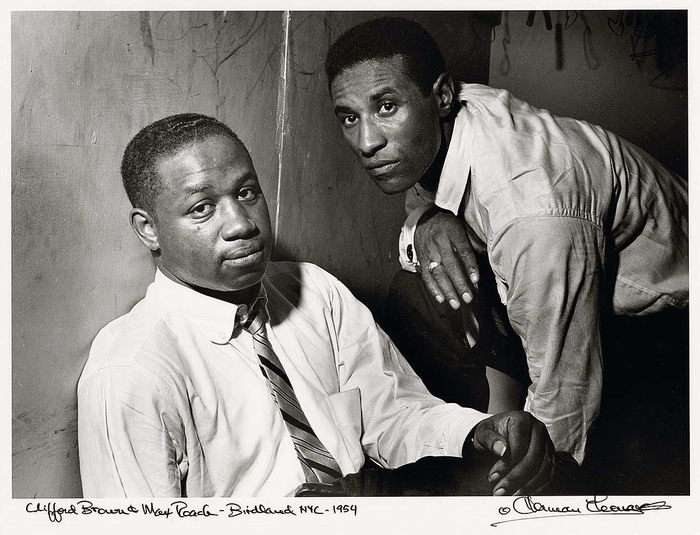

Born in 1924, Max Roach was already an accomplished musician when he founded, in 1954, a remarkable quintet with Clifford Brown on trumpet, Harold Land on tenor sax, Richie Powell on piano and George Morrow on bass. The sound of this quintet, the music they would play, is characteristic of the then beginning hard-bop style — combining the velocity of the bebop with a fuller sound and more sophisticated arrangements. (Another important hard bop quintet would be that of Art Blakey — another drummer ! — and his Jazz messengers.)

Their first recording features tunes by notable composers, but we owe three of them to Brown. The one I chose for today, Daahoud, has a slightly unusual form. The melody starts in anticipation by a full bar, while the musicians only play one full note on the first bar. This unbalance is kept during the full AABA form, an 8 bar motive in Eb which is repeated twice, another 8 bar motive that modulates in Bb, which leads to the initial 8 bar motive. That classic pattern is then enriched by an element of surprise by the addition of 4 bar bridge in repeated II-V-I. Choruses follow: trumpet, piano, saxophone, and drums, and the musicians end the tune by replaying the melody, 3 bars at the drums, and a finale.

“Daahoud”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, 1954

In 1955, one year after Max Roach and Clifford Brown started their quintet, the saxophone player Harold Land left the band to settle in California; he was then replaced by Sonny Rollins. In 1956, Sonny Rollins led a quartet session with Tommy Flanagan on piano, Doug Watkins on bass and Max Roach on drums — Saxophone Colossus.

The song that opens the recording is a calypso, a caribbean rhythm, which energizes all musicians. Listen how Roach opens the tune by setting the groove up using the hi-hat cymbal (on beats 2 and 4), plus the clave and occasional rhythmic ornements, on which the Rollins can lay down his melody in a quite relaxed way. Follows a long saxophone chorus and which ends abruptly, and Roach takes a wonderful chorus sometimes reminiscing of the melody (on the cymbal, in particular) never abandoning the basic pulse. A second chorus, shorter, on saxophone, another one on the piano, a last exposition of the melody, and that’s it!

“St Thomas”, Saxophone Colossus, Sonny Rollins, 1957

Let’s go back to Max Roach/Clifford Brown’s quintet and listen to another tune of that fantastic recording. This tune, Jordu, had been composed in 1953 by the pianist Duke Jordan, and although he recorded it in 1954, the interpretation of the Brown/Roach quintet still remains a reference. The AABA melody is exposed with immense suavity, with more emphasis in the B part. (Jordan’s versions, at least for the ones I know, are played faster, and flatter.)

There’s something interesting to notice in the way Roach accompanies the melody: there’s two ways to emphasize the melody when you are a drummer: you can play with it, or you can announce it, and Roach offers these two options.

After choruses by Brown, Land and Powell, the musicians start trading fours with Max Roach, until the drummer embarks in a full fledged solo, and expose the melody one more time.

“Jordu”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, 1954

I started this series in 1966 and went back to 1954 and the great Clifford Brown/Max Roach quintet, and already mentioned that at that time, Max Roach was already a prominent musician. We’ll eventually listen to Roach’s debuts as we know them, in particular when he played with Charlie Parker, but for today I decided to settle to a recording Roach did as a sideman, in Miles Davis’s Birth of the cool nonet. That was 1949, and for Miles, now’s was the time to overtake bebop and inventing the “cool” movement.

It’s hard to tell what’s really cool in this music, part of which is played really fast (go listen to “Move”, for example) but compared to classic bebop, it features a more mellow sound, with richer 2 or 3-voice arrangements, in particular in the middle or below of improvised parts.

Today’s theme, Godchild, was composed by baritone saxophone player Gerry Mulligan. Max Roach plays brushes during the initial exposition and takes his sticks afterwards where he plays a simple and effective grooves with some accents on the floor tom. It’s what I needed tonight — I hope you’ll enjoy it!

“Godchild”, Miles Davis, Birth of the cool, 1949

Recorded live in 1954, this version features Dinah Washington on vocals, accompanied by Brown/Roach’s quintet and a few other musicians. Dinah Washington starts by singing the song almost without any accompaniment, just the piano playing some notes, and without any rhythmic feel. At some point, the rhythm section comes in and provides an afro-cuban atmosphere to the tune. A few choruses, played with a straight jazz feel, come after that, until Dinah Washington retakes the song, back to the afro-cuban feel. All these atmosphere sound a bit strange on a single recorded track — after all, the album is called Dinah Jams ! — but the audience seems to have enjoyed this moment.

“You Go To My Head”, Dinah Washington and Clifford Brown, Dinah Jams, 1954

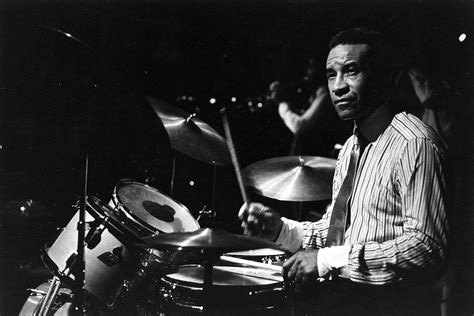

In 1945-1949, Max Roach had been a prominent bebop drummer, a jazz style he contributed to shape. Indeed, together with Kenny Clarke, he found a new way of keeping time by using the ride cymbal to play the classic syncopated rhythm figure [ding - ding-ah - ding - ding-ah] (which can be played in triplets, in 8th notes, or even in quadruplets, according to the tempo and mood), and reserved the bass drum (which was very loud) for accents (“bombs”). That left more place in the music to the soloists for improvising.

Charlie Parker composed this tune for Max Roach’s first recording session as a leader (with Hank Mobley on saxophone, April 1953). Together with Percy Heath on bass and Al Haig on piano, they recorded the following version in July 1953.

“Chi-Chi”, Charlie Parker, 1953

10 years before yesterday’s recording, Max Roach was already leading the bebop scene and recorded with all the great.

Today’s song is a Don Byas composition, Living My Life, taken from an album led by Don Byas — Savoy Jam Party — made from 4 recording sessions from 1944 to 1946 in which he shares the drums with 3 other drummers I had never heard of. I want to share two songs of that recording with you, because the way Roach accompanies them is strikingly different.

Living My Life (*) is a kind of slow drag, AABA form, at a moderate tempo (approx 120 bpm), in AABA form where the saxophonist takes all the light: he exposes the theme, takes one chorus, leaves some space to the piano for 8 bars and takes back the melody to conclude. Roach’s accompaniment is very minimal : he plays quarter notes on the snare drum all along, probably playing sort of flas with brushes — that allows him to create a longer sound — but nothing more.

I had explained a few days ago how Max Roach and Kenny Clarke had helped create bebop by switching the beat from the snare drum to the ride cymbal. Here, you have a great example, recorded in August 1946, of what hadn’t yet happened!

“Living My Life”, Don Byas, Savoy Jam Party, 1946

(*) Of course, it’s also the title of Emma Goldman’s autobiography, but that’s an entirely different story…

Yesterday, we had listened to a 1946 recording by Don Byas in which Max Roach played in a pre-bebop way, marking all beats on the snare drum. Today’s tune comes from the same recording, but we can hear that something has changed.

First of all, St Louis Blues is an extremly famous W.C. Handy composition from 1914, it is the first ragtime tune to have been published in score, and some even say it’s the most recorded song in the first half of 20th century. Moreover, although this song is called St Louis Blues and W.C. Handy himself codified the blues form as a 12 bar form, that song does not obey this for. In fact, part of it is explicitly an afro-cuban rhythm — that of an habañera.

In this version, with Max Roach on drums, you can get the afro-cuban in the first part of the theme: Max Roach plays 16th notes on the rim of the snare drums, and the accents he gives suggest the habañera, as if it were a clave on woodblock. But on the second part and in the choruses, you can hear the jazz feel on the ride cymbal.

One day, we’ll listen to yet another version of that song that Max Roach recorded in 1965, this time played as a jazz waltz!

“St Louis Blues”, Don Byas, Savoy Jam Party, 1946

A sweet and kind melody for tonight. The times they are changin’, and not for the best. Clifford Brown plays this ballad softly, with a lot of kindness — and it’s wonderful… And at 2:25, you find some energy to swing a little bit, for not for too long. It’s already late, my friends. The day has been long, probably exhausting, or maybe that was the day before, and is there hope in everything that we have to endure. The piano will let you fall asleep, maybe, but no, that’s not the time yet, and you need that energy from the trumpet at 6:00 to sing that song again, that there is so little hope, but that you are still there, alive, for the best. Good night, friends.

Back to the bebop period, where Max Roach serves as a sideman. Ellis Larkin is playing a stride blues on the piano, and Max Roaches draws a brushes tapestry beneath him. Then comes the guitar of Jimmy Shirley, followed by a bass chorus by Oscar Petitford. At 2:25, after some short questions and answer between piano and drums, we can finally hear the boss, Coleman Hawkins on tenor saxophone. This happened in New York City, 18 December 1943 — Max Roach’s first recording!

“Blues Changes”, Coleman Hawkins, 1943

Another bebop tune with Max Roach as a drummer — I need to spend some time listening to those tunes before returning to 1955. So this song comes from Dexter Gordon’s first album, Dexter Rides Again, which is assembled from three recording sessions in 1945 and 1946. That one dates from January 1946, besides Gordon on tenor saxophone and Roach on drums, you can hear Leonard Hawkins on trumpet, Bud Powell on piano and Curly Russell on bass. Due to the recording medium — 78 rpm vinyl disks — the song needed to be short: barely 3 minutes, but 3 minutes full of energy pushed forward by this unmistakable riff.

“Dexter Digs In”, Dexter Gordon, Dexter Rides Again, 1958

1946 again, Max Roach holds the drums for saxophonist Stan Getz ; Curley Russell is on bass (as for yesterday) and Hank Jones on piano and at the composition for this fierce tune. On the 10" 78 RPM, the musicians are presented as “The Be Bop Boys featuring Stan Getz Tenor Sax”. On that 31 July 1946, New York City was really hot!

“Opus de Bop”, The Be Bop Boys featuring Stan Getz, 1946

Max Roach had played with Charlie Parker as early as 1945, but that recording is taken from a legendary concert in Toronto, Canada, on May 15, 1953 — Live at Massey Hall, there were Charlie Parker on tenor saxophone, Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet, Bud Powell on piano, Charles Mingus on bass, and of course Max Roach on drums.

This Tadd Dameron composition is pure bop — a very simple melody, almost just a riff repeated following a chromatic descent (IV-V-1) which serves as a pretext for improvisations. Many jokes in the solos — listen how Parker quotes Carmen, and Gillespie responds with Do nothing till you hear from me?

It’s interesting to listen to Roach’s playing too: after a 4-bar improvisation, he mostly plays a swing rhythm on the ride cymbal during the exposition of the theme (goes to the hi-hat for the B-part), with accents on the snare and floor drums, some parts with an afro-cuban feel, but brushes on Mingus’s solo, until everybody rejoins (rejoices) for the theme. Everyone in this legendary band swings like hell, the audience is on fire. I hope you’re all well!

Still in my chronological discovery of Max Roach’s be bop era, mostly as a side man, and this time within a quartet led by Miles Davis on trumpet. Percy Heath is on bass and John Lewis on piano. The theme is a melancholic ballad, composed in 1936 by Benny Carter and Spencer Williams. After a small introduction on the piano, the trumpet takes the lead and plays the melody, with a minimalist accompaniment from which the musicians won’t depart, even during the very short piano chorus where John Lewis, to say the least, doesn’t try to show his virtuosity.

That recording is from Miles Davis’s album Blue Haze, where the trumpet player experiments various quartets (Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey also take the drums, Horace Silver on piano, and Charles Mingus as well!) recorded in 1953 (as for that sone) and 1954.

It’s late, friends,

lights are low in the club,

it’s raining outside, or your flat may be empty and cold

let’s indulge ourselves one more tune…

“When lights are low”, Miles Davis, Blue Haze, 1955

Here is Oscar Pettiford’s sextet playing compositions by the critic and music journalist Leonard Feather, who, as one can hear, was also a fine composer. (With Mingus, he arranged poems of Langston Hughes.)

Together with Roach on drums and Pettiford on bass, there is Kai Winding is on trombone, Al Cohn on tenor saxophone, Tal Farlow on guitar, Henri Renaud on piano. This is a short piece anyway — after the melody where the sextet plays a nice arrangement, you got solos by Cohn, Winding, Farlow, Renaud, and Pettiford, and it’s time to play the melody and conclude.

“Ondine”, Oscar Pettiford Sextet, 1954

April 1953. Time for Max Roach to start his own band, as a leader. Hank Mobley is on tenor saxophone, Walter Davis Jr on piano, and Franklin Skeete holds the bass. Just One of Those Things is a Cole Porter composition, a true standard according to the definition of a standard, since this song was part of a musical — Jubilee. The initial composition was labeled as a foxtrot, and played at moderate tempo — 120bpm — it seems vocal versions keep that tempo.

Having a bebop band with no singer allows to play it faster, although you can’t feel that upcoming speed at Roach’s short intro, which plays quite freely on the cymbal and the toms. The last two short notes on the bass drum send the start signal — and they are quarter notes, so that the tempo is roughly 200bpm. The melody is played by Mobley on saxophone — Roach essentially plays 8th notes on the ride (with almost no swing in it) and some accents on the bass drum. After the melody, the saxophone starts a riff that seems to mean he’s going to chorus, but no! Roach takes the lead for a very fast drum chorus where he doubles the tempo, playing all quarter notes on hi-hat and 8th notes on the bass drums. That marks a strong and fast pulse above which he plays rudiments on the snare drum. Only then can Mobley, and then Davis, do their own solos, until Mobley redoes the melody and Roach concludes with a small drum finale.

“Just One of Those Things”, Max Roach Quartet, 1953

Max Roach and Clifford Brown with their quintet play this astonishing composition. Listen to the long intro, where the horns imitate the busy city of Paris, reminiscing of Gershwin’s American in Paris, and then, when the melody starts, how the piano fills the end of the first 8 bars with hints of the Marseillaise or, for the next one, of the classic French cancan. They’re having fun, and play this fast tune with both energy and lightness. George Morrow is on piano, Harold Land on tenor sax and Richie Powell on bass. Enjoy!

“Parisian Thoroughfare”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach quintet, 1955

We continue our exploration of the Max Roach / Clifford Brown quintet.

A 1938 Ray Noble composition, from his Indian Suite (in 5 parts, all bearing the name of an Indian tribe), it didn’t become part of the jazz canon until Charlie Parker proved that it was possible to improvise on it. It is also very fast, 240bpm, — and if, by listening to the melody, you think it isn’t that fast, it is because the melody is written in full notes. It is from the drums that you hear the pulse that the musicians have to internalize to play that song, especially in the choruses. Also, the bridge is written as a II-V-I progression, hence its tonality changes every second… you can get how tough it is to improvise on it!

Here, all musicians expose their virtuosity, without losing on musicality… The first drum chorus is probably hard to follow, but you get a second chance when the musicians replay the melody, because Roach takes a new chorus on the bridge part.

A great version !

“Cherokee”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach Quintet, Study in Brown, 1955

A 1929 song by Cole Porter, it turned into a wonderful jazz standard that allows the creativity of musicians to expand in unforeseen directions. Despite what the title of this album may suggest, it was not recorded “At Basin Street”, New Orleans, but in New York City’s studios of the Capitol company, February 1956. It features once again the Clifford Brown / Max Roach quintet, except that Harold Land left the band to live in California, to be replaced by Sonny Rollins! George Morrow is on bass, Richie Powell on piano, and these five guys embark in a fast-paced rendition of that tune.

After a long intro on a single chord, the theme starts on the trumpet, and the saxophone answers for the bridge, and we’re set for a succession of choruses propelled by Roach’s drumming : Brown, Rollins (who takes his time, starting with a 2-note motive he will repeat several time, recall at various places, and end with it), Powell, Morrow (with an interesting counterpoint by Roach and Powell), then a long riff passage that launches Roach’s chorus, at 5:00 on. Here, we have an extremely dense playing with the sticks, with accents on the hi-hat and cymbals — Note how Roach departs from the standard way of playing the hi-hat: it is no more played regularly on beats 2 and 4, as a pulse keeper, but as an autonomous melodical instrument, to which the other cymbals respond. Time for a 2-voice chorus on trumpet/saxophone, 8 bar each, then 4 bar, to finish by playing a melody at unison. The song ends like it started, on a pedal point.

“What is this thing called love?”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, At Basin Street, 1956

At the same time where the quintet of Max Roach and Clifford Brown was emerging as a new force in jazz, Max Roach served as a side man in various bands. Tonight’s recording is exactly that quintet, but for the leader since it is now Sonny Rollins who leads the band.

The song, Valse Hot, is a composition of Sonny Rollins, but Max Roach will later record it again. You can hear in that version, already in 1956, with how much ease he can bring a jazz feel to the waltz rhythm. One of the key of his playing is understating the third beat: instead of playing boom-tcheek-tcheek, boom-tcheek-tcheek…, he plays boom-tcheek-(hush), boom-tcheek-(hush)… and that makes a tremendous difference.

“Valse Hot”, Sonny Rollins, Plus Four, 1956

A beautiful and tender ballad for tonight. Because we deserve this quietness, this calm, be it for three minutes only. George Morrow sings the melody at the bass with a little harmonic support of the Richie Powell’s piano and consistent brushes by Max Roach. A vague attempt to swing during the bass chorus, but we’re back to the sound of brushes. No horns, no effects, nothing but nostalgia.

“These foolish things”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, 1954

Back to 1955 again when, together with his own quintet with Clifford Brown, Max Roach served as a side man for various bands. Today, the leader of the band is Charles Mingus on bass, with Eddie Bert on trombone, George Barrow on saxophone and Mal Waldron on piano. And Max Roach is not a side man, he’s a guest! (The usual drummer of Mingus’s band is Willie Jones). So Max Roach appears on two tracks of that live album (recorded at Café Bohemia, New York, December 23, 1955), and this song, Drums, of which both Mingus and Roach are credited as composers, puts him in front of the scene.

“Drums”, The Charles Mingus Quintet + Max Roach, 1955

For his second album as a leader, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley gathered an octet in August 1955, with arrangements by Quincy Jones. On three tracks, Max Roach is on drums — it’s Kenny Clarke on the other ones.

Tonight was the first time I heard this song, Rose room, a 1917 composition by Hickman and Williams, which was famous in the swing era, and Jones’s arrangement definitely do justice to the spirit of swing. Apparently, Ellington revived the song in 1932, and “borrowed” its chord progression to compose “In a mellowtone”. Max Roach gives a great background here, with a light but directive style most of the time, and uses the silences at the end of the musical phrases for bebop-style interventions that relaunch the music (can you get them in the exposition of the theme)? There is also a nice trading in fours between Adderley and Roach at the end of the song (Roach doubles the tempo there, so it sounds as if they play 8 bar each).

“Rose Room”, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley, 1955

22 June 1956. Sonny Rollins enters the van Gelder studios at Hackensack to record a somptuous album, with Doug Watkins on bass, Tommy Flanagan on piano and Max Roach on drums. Five exceptional songs.

We had already listened to “St Thomas”. Tonight is “Blue Seven”, a composition of Sonny Rollins that alternates between calm are dense phrases, a structure that allow the saxophonist to build a great chorus. Max Roach himself takes the opportunity of this medium tempo to offer us a drum solo based on the melody. That’s something which may be hard to grasp when you listen to the recording, but in an episode of the Alain Gerber Black and Blue radio show, “À la manière de Max Roach” devoted to Roach, the drummer and music educator Georges Paczynski made the experiment of playing the chords on the piano during the whole drum chorus — and then, suddenly, one realizes what the drummer was really doing : rather than showing off his dexterity, he was actually giving his own interpretation of the melody. The saxophonist takes back the lead, proposes a second version of the melody, offers a new chorus, and then engages in a discussion with the drummer by trading fours with him.

“Blue Seven”, Sonny Rollins Quartet, Saxophone Colossus, 1956

I should also add that Paczynski is the author of a great 3-volume history of jazz drumming (Une histoire de la batterie jazz, Outre Mesure, 1998-2005). He devotes a chapter of his volume 2 to the innovations by Kenny Clarke and Max Roach. It is also there that he gives details about Roach’s chorus on Blue Seven — Roach starts at bar 5, after something that looks like Rollins wanted to trade fours. But Rollins doesn’t play again on bar 9, so Roach goes on, completes the 12 bar theme, and goes on for 5 or 6 more choruses. Paczynski also explains how he understood, by playing the chords on the piano while he was listening to that chorus, that Roach was basing his chorus on the harmonic changes of the song.

Still floating around spring 1956, this time introducing Johnny Griffin, on tenor saxophone, with Wynton Kelly on piano, and Curly Russell on bass. This blues (a 12 bar form) composed by Griffin is based on the repetition of quite a simple looking riff and serves as a pretext for all musicians to show their musicality, without too much virtuosity. No chorus for Roach, but some of his interventions are interesting, especially during the piano chorus, and at the end of the bass chorus, before Griffin retakes the melody. Nice and easy. So it seems, at least.

“Nice and Easy”, Introducing Johnny Griffin, 1956

1956, Clifford Brown / Max Roach quintet, with Sonny Rollins on saxophone, George Morrow on bass and Richie Powell on piano. It comes from the album At Basin Street, which features three compositions by the pianist. Tonight’s track is one of them, a very fast hard bop piece where all musicians show their dexterity, from the exposition of the theme which Brown and Rollins play together (it is possible that Rollins plays a fifth lower), to the choruses which run as fast as possible, the one after the other. (Listen how strong the rhythm section plays behind the soloists!) With a bit of a paradox, it becomes quieter for the piano chorus, but that’s only for a moment. Roach’s chorus is very dense as well, and one needs to step back a little to listen to its melodic inspiration. Back to the theme, and it’s time to conclude this short and fast piece.

“Powell’s Prances”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, At Basin Street, 1956

Same album as yesterday, Clifford Brown / Max Roach At Basin Street. Same composer, Richie Powell. Completely different mood, though.

A calm ballad.

The song of a trumpet that pulls away the tears out of our sadness.

Have a good night.

“Time”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, At Basin Street, 1956

Max Roach and Clifford Brown with strings. Arrangements by Neal Hefty. Recorded January 1955. It’s so sweet we want it to go on forever. But we can’t.

Some people know the story already, but some don’t, and I know it, and I can’t manage to tell it right. There are things that make you sad. It’s about the passing of time, about people who go, and those tears, they’re not caused by the smoke in the jazz club.

“Smoke Gets Into Your Eyes”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach with strings, 1955

25 June 1956. Clifford Brown and Richie Powell play at a jam session in Philadelphia, with local musicians. The night is supposed to have been memorable. Then they take their car towards Chicago, where they had to play with the quintet. The musicians need to rest, and Nancy Powell, Richie Powell’s wife, drives. Alas, under a heavy rain, we suppose she lost control of the car which crashed of the road. All three died in the accident.

Nancy Powell was 19; Clifford Brown, 25; and Richie Powell, 24.

All we have, now, is “Memories of You”.

“Memories of You”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach with strings, 1955

In 1957, the saxophone player Benny Golson composed a song to the memory of Clifford Brown — “I remember Clifford”. There is an awsome version of it by Art Blakey’s Jazz messengers (with Golson on saxophone), recorded at Paris Olympia in 1958.

The present version seems to be the only one which Max Roach recorded. That was in 1981, in the album Chattahoochee Red. But what I hear from this version is that 25 years later, Max Roach’s wound hadn’t healed.

Cecil Bridgewater is on trumpet, Odean Pope on saxophone, Calvin Hill on bass.

“I remember Clifford”, Chattahoochee Red, 1981

Despite the tragic death of Clifford Brown and Richie Powell, Max Roach managed to run a quintet, with Kenny Dorham on trumpet and Ray Briant on piano. Recorded in september 1956, the album +4 features two compositions of the drummer, in particular this one, Mr. X, in the pure tradition of hard bop: short rhythmic phrases which are barely more than riffs, with a more lyrical bridge.

Around 3:20, it is very surprising to recognize Sonny Rollins playing Mr PC, a famous composition by John Coltrane which, however, would only be recorded in 1959. At that point, the musicians start trading in fours, with Max Roach playing every four other bars. After some time, he runs into a dense chorus, sustained with block chords on the piano that delineate the song’s changes.

“Mr. X”, The Max Roach Quintet, +4, 1956

October 1956. Max Roach takes part in Thelonious Monk’s quintet. The piece that gave the album its title is supposed to have been a nightmare to record, because of its complexity, so that the producer Orrin Keepnews built it from 25 takes. Sure, that piece is awkward, with its ABA form which is played once at a normal tempo, and the second time with a double time feel. On the other hand, it seems, by listening to Max Roach’s chorus, that he so perfectly understood the composition he offers us a drum interpretation.

“Brilliant Corners”, The Thelonious Monk Quintet, Brilliant Corners, 1957

A 1957 recording from the Max Roach + 4 album. This Victor Young composition, “Love Letters” was very successful in 1945 — it just lost the Academy Award for the best song against “It might as well be spring”!

This version is interesting because it features a full range of atmospheres, as if it were a full movie — it starts with a melancholic introduction by Sonny Rollins, goes on to a joyful exposition of the melody by Kenny Dorham on trumpet, and turns to a wonderfully sad piano solo by Bill Wallace, after which it takes another look, swinging like life at its happiest (the saxophone and piano choruses, for example), to end in the beginning’s mood. Max Roach doesn’t put himself forward in this piece, but still, together with George Morrow, he’s driving this piece resolutely.

“Love Letters”, Max Roach, + 4, 1957

In April 1957, Max Roach participated in several sessions for J. J. Johnson’s quartet, a trombone player he had already played with in the Benny Carter orchestra, already by 1944 ! Johnson was actually one of the first trombone player to engage in bebop. There is a beautiful recording with the other trombone player Kai Winding. In the 70s, Johnson would move to California and be also famous as a TV film composer, for example for of Starsky & Hutch, or The Six Million Dollar Man!

This song, “100 Proof”, is a fast bop composition by Johnson himself. This version features two long choruses that show his dexterity, separated by a piano chorus by Tommy Flanagan. For the second one, Roach switches sticks to brushes, which he keeps during the bass chorus which Paul Chambers plays on the bow. Then it’s time for a melodic chorus by Roach, a last version of the theme, and quite an abrupt ending!

“100 Proof”, J. J. Johnson, Blue Trombone, 1959

1957 is also the year of Max Roach’s first recording with the singer Abbey Lincoln. This album, Abbey Lincoln with the Riverside Jazz Stars (Kenny Dorham, Sonny Rollins, Wynton Kelly, Paul Chambers and Max Roach), will be the first of 10 years of creative music, mutual love, and, as we will see later in this series, of many battles for civil rights.

This song, “Don’t Explain”, is a wonderful ballad written by Billie Holiday and Arthur Herzog Jr. This version is amazing in so that the musicians (especially Dorham and Rollins) manage to bring their own creativity into the playing without hindering Lincoln’s moving interpretation.

“Don’t Explain”, Abbey Lincoln and the Riverside Jazz Stars, 1957

It’s incredible how many different projects Max Roach have joined in that year 1957. Tonight, we meet a team of musicians we’ve already heard, except for the leader of the session, the saxophone player Benny Golson. We also have J. J. Johnson on trombone, Kenny Dorham on trumpet, Wynton Kelly on piano, Paul Chambers on bass and, of course, Max Roach on drums.

You may have noticed how the presence of a second horn allows for a subtle change in the mood, from be bop to hard bop. Here we have a third one, and there is a kind of west coast feeling in the arrangement, allowed by the three distinct pitch ranges of the trombone, the saxophone and the trumpet.

Blues on down is a Golson composition. The form is short, 12 bars, with a very common harmony. A good pretext for almost 12 minutes of improvisations. Every player does his own. Every chorus is perfect, and Roach’s is unmistakable!

“Blues on Down”, Benny Golson, The Modern Touch, 1958

Recorded in February/March 1958, The Freedom Suite is a Sonny Rollins album in trio — with Oscar Pettiford on bass, and Max Roach on drums. (Apparently, Rollins had been fed up of piano players coming up late and he made several recordings without piano during the years 1957-1959.)

The main track is a long composition in many parts (hence the title “suite”) where the instruments are not reduced to their traditional role in jazz — all of them contribute to both melody and rhythm — and we can hear that something in the music is trying to gain freedom. There is freedom in music, but the claim is of course political.

Allow me to copy verbatim Rollins’s liner notes: “America is deeply rooted in Negro culture: its colloquialisms; its humor; its music. How ironic that the Negro, who more than any other people can claim America’s culture as his own, is being persecuted and repressed; that the Negro, who has exemplified the humanities in his very existence, is being rewarded with inhumanity.”

“The Freedom Suite”, Sonny Rollins, Freedom Suite, 1958

That’s a 1930 song by Cole Porter (from the musical The New Yorkers) which is very nice to play, because of its AABA form, with an annoying subtlety that the AABA is played twice, and 8 bars are added, which you may forgot if you don’t pay attention… The A part is in minor, the B part is in major, and nowadays, the A part is sometimes played with a latin feel, while the B part is played in swing style…

Tonight’s version was recorded live at Newport in 1958, and it is very interesting to compare that version with other versions recorded the same year: In Cannonball Adderley’s quintet (Something else; Art Blakey is on drums) or Miles Davis’s sextet (it appears in recent editions of Kind of Blue, with Jimmy Cobb), or the next year’s Dexter Gordon (GO, with Billy Higgins), not speaking of the vocal versions (Billie Holiday recorded a beautiful one in 1952).

You’ll hear : Max Roach has already past the musical style he had contributed to shape since 1944 (be bop, and then hard bop). Surely the five musicians play that song (with Max Roach, there is Booker Little on trumpet, Ray Draper on tuba, George Coleman on tenor sax and Art Davis on bass), but most of the music is a common improvisation, and the rhythmic support is much closer to what would become common in free jazz.

“Love for sale”, Max Roach Quintet, At Newport, 1958

Same line up as yesterday, for an album recorded a few months later. The music is quieter, almost meditative, but the subtext is certainly not : Deeds, not Words, it says. (And a few years later, Max Roach will insist!).

Except for the introduction and the ending, where the horns play a beautifully sad arrangement, most of the tune features only the bass, the drums and one of the horns. Listen how bass and drums play a kind of counterpoint to the improvisations.

Bill Lee, the composer, passed away last year. He was a bass player, recorded with Bob Dylan, Simon & Garfunkel, and many other, and composed several operas. The father of Spike Lee, he also wrote the music of some of his movies — in particular Do the right thing or Mo Better Blues.

“Deeds, not Words”, Max Roach, Deeds, not Words, 1958

Same album as yesterday, but today is a solo piece.

Everything is built around a simple rhythmic figure (hush-tee da-dah) but where the offbeat note is slightly accentuated. Max Roach moves this figure everywhere on the instrument, and improvises around it, in a very structured way. (See these 3 sections of 16 bars which start with 4 bars of swing rhythm?) Max Roach is said to have introduced the concept of melodic drumming. Maybe after having listened to this piece, that will not sound like an oxymoron to you!

“Conversation”, Max Roach, Deeds, not Words, 1958

For those who can read music, there’s a transcription on Francesco Vecchio’s blog! Here are the first 20 bars of it:

A Max Roach composition in the style of hard bop, which I believe is really beautifully arranged, and where the tuba plays a big melodic part. The drummer alternates between playing a straight rhythm, either on sticks or brushes, or playing counterpoint; the bass line during the drum solo is also very interesting.

“Tuba de Nod”, Max Roach, Award-Winning Drummer, 1959

In 1959, Abbey Lincoln records Abbey is Blue with two different bands. Among the 10 songs of this beautiful album, 4 are accompanied by Max Roach’s sextet. Tommy Turrentine is on trumpet, Stanley Turrentine on tenor saxophone, Julian Priester on trombone, Cedar Walton on piano, and Bob Boswell on bass. One of these 4 songs is a composition of Lincoln : “Let up.”

“Let up”, Abbey Lincoln, Abbey is Blue, 1959

A Kurt Weill song, from a 1959 recording by Max Roach +4 (some tracks feature Abbey Lincoln). But here we have a bass/drums/piano trio only : Ray Bryant and Bob Boswell. That’s a sweet song, and Bryant plays it quite bluesy.

“Moon Faced and Starry Eyes”, Max Roach +4, Moon Faced and Starry Eyes, 1959

This is a composition by Max Roach, from his album Percussion Bitter Sweet, recorded in 1961. Booker Little is on trumpet, Julian Priester on trombone, Eric Dolphy on alto saxophone, Clifford Jordan on tenor saxophone, Mal Waldron on piano, and Art Davis on bass.

Let me copy the liner notes (by Margo Guryan) from the album:

“Praise for a martyr was composed in homage to all the men and women who have sacrificed their lives fighting for their individual and collective freedoms. There is, again, a pulling quality in the voicing of the chords which is both somber and respectful. As the improvisation section progresses, you begin to notice three repeated notes dwelled upon by the bass. This repetition gives one the feeling of a solid foundation being laid ; a feeling that the martyr has not died in vain, but that his struggle will be continued by those who remember him. The soloists are Clifford Jordan, Julian Priester, Booker Little and Mal Waldron.”

“Praise for a Martyr”, Max Roach, Percussion Bitter Sweet, 1961

Tonight, France is honoring the memory of Missak and Mélinée Manouchian by laying their ashes in the Panthéon. Manouchian was the head of a group of communist, resistants, mostly Jews and of immigrant origin, who fought for freedom against the Nazi occupation and the collaborating French Vichy régime.

Manouchian was shot by the Nazis on this day, February 21st 1944, 80 years ago, together with 21 of his comrades.

Let this song honor their memory.

Same album as yesterday, with vocals by Abbey Lincoln.

The music is by Max Roach and the lyrics are by Chips Bayen, a lyricist, soprano saxophonist, and musician manager (of Charlie Parker in particular, and Elmo Hope wrote the song Chips), he was the son of the Ethiopia emporer Haïlé Selassié.

The song starts with a heartbreaking cry on the horns, accompanied by cymbals, and continues with the voice of Abbey Lincoln, simply accompanied by piano and bass. After the first verse comes the moment of choruses, first Eric Dolphy (I guess). It goes on with a drum solo (at 3:42), where Max Roach articulates short phrases, separated by noticeable silences, as if he speaked — there is anger, but it is as if it couldn’t go out in full. (In her liner notes, Margo Guryan notes that as well, she adds: that “Max describes it as ‘taking a breath’, a technique often overlooked by many musicians.”) Then the piano/bass/drums trio resumes for the second verse, with a nice background horn accompaniment.

“Mendacity”, Max Roach, Percussion Bitter Sweet, 1961

At an era of moral panics, it is good to remember that in 1960 (and already in 1900, and already in 1850, and already…) people had the sense that the power was confiscated in the benefit of a few.

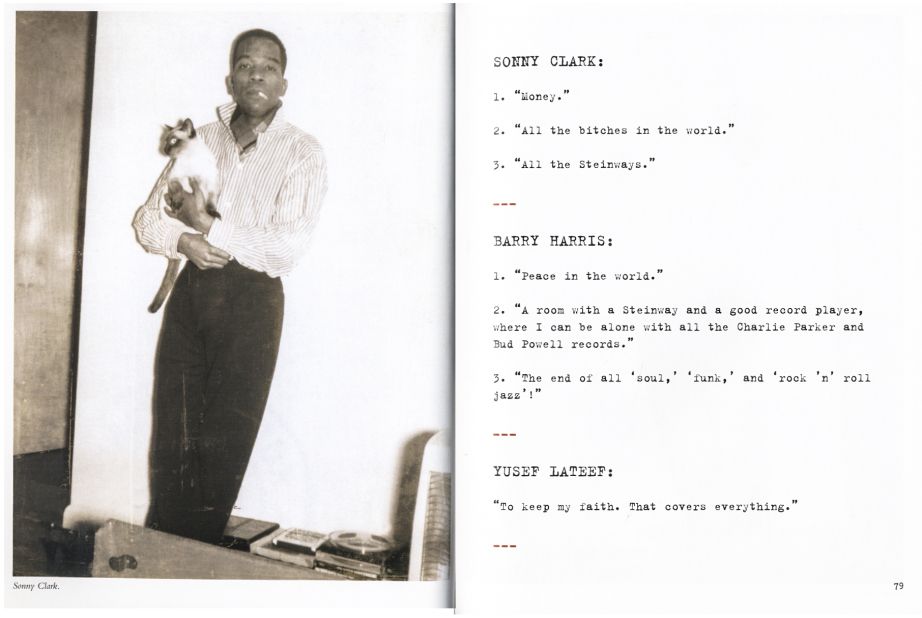

Let’s cool down a little bit after the two demanding tracks of the last days. Recorded in March 1960, today’s song is a Sonny Clark composition, recorded by his trio. Sonny Clark is on piano, George Duvivier on bass, and Max Roach on drums.

This song, of course, is a homage to baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter whose house was a home for jazz musicians — Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk in particular.

“Nica”, Sonny Clark Trio, 1960

She had asked jazz musicians about their “three wishes” — she published a book with them, together with Polaroid photographs she had taken.

I don’t have that book, and I don’t know whether Max Roach told them his wishes, but Sonny Clark’s are clear: 1. “Money” 2. “All the bitches in the world” 3. “All the Steinways”

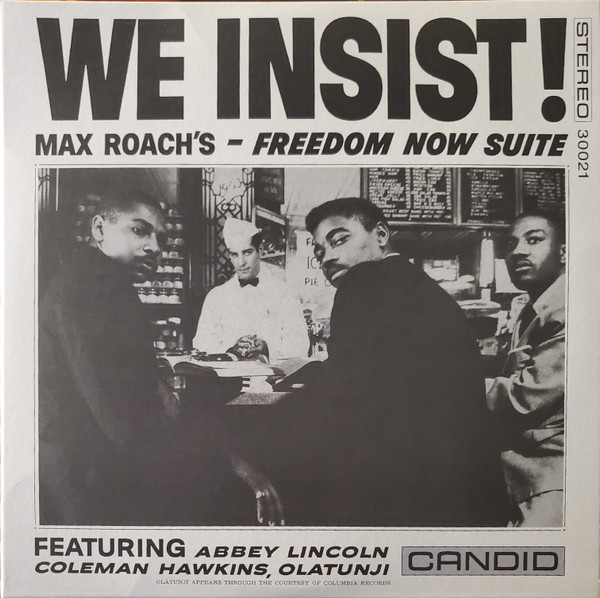

Two years after Rollins’s Freedom Suite, Max Roach recorded his own political claim — Freedom Now Suite. It consists on five pieces, written for the centenary of the Emancipation proclamation (1963). The album was published in 1960 under the title We insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, all written in huge block letters.

The first track is an evocation of the slaves working in cotton fields, under the brutal overseeing of “Driva’ Man” — a personification of the white man.

The lyrics are sung — almost chanted — by Abbey Lincoln, simply accompanied by a tambourine. Coleman Hawkins then takes again the melody, backed up by the trumpet of Booker Little, the trombone of Julian Priester and the tenor saxophone of Walter Benton, together with James Schenck on bass. The song is a blues in 5/4, and — unusually for a jazz piece — it is played by accentuating the first beat of every bar, first on the tambourine and then by a rim shot on the drums

“Driva’ Man”, Max Roach, Freedom Now Suite. We insist!, 1960

We continue the listening of Freedom Now Suite — We insist!. The second track, “Freedom Day”, has already been recorded a few months ago, in Paris, under the title “Liberté”, but without vocals. It celebrates the 1865 Emancipation proclamation, and the lyrics, sung by Abbey Lincoln, depict the anxiety, the surprise, the disbelief that they could be free.

And indeed, as the claim of the whole album recalls, with its cover picture from the 1960 North-Carolina sit-in movement, they still aren’t fully free.

This hiatus is rendered by the discrepancy between the rhythmic feelings imposed by the various players — the rhythm section plays very fast, while the melody is written around full notes.

“Freedom Day”, Max Roach, Freedom Now Suite. We insist!, 1960

I am quite a fetishist about numbers, and I’m glad that this song gets this number 50. In fact, there are 3 musical pieces that made me cry: Mozart’s piano concerto No. 23 (when the clarinet comes in), Barbara’s “Dis quand reviendras-tu ?”, and this tune, the first time I discovered it by surfing on YouTube.

This is a duet between Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln, but there are no lyrics. The title says it all; it starts like a prayer, violently erupts in protest, until it finally finds some peace.

Opinions vary about this piece which forms the central part of Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite. As for myself, I cannot not be moved by the “Protest” part, and without it, the album title We insist! wouldn’t be as strong.

“Triptych: Prayer/Protest/Peace”, Max Roach, Freedom Now Suite. We insist!, 1960

The last two tracks of Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite have a different flavour. “All Africa” is a percussion/voice song in which African and/or Afro-Cuban rhythms (played by Babatunde Olatunji on congas, and, for the second part of the track, by Raymond Mantillo and Tomas du Vall) respond to Abbey Lincoln’s singing.

“All Africa”, Max Roach, Freedom Now Suite. We insist!, 1960

At that epoch, which was the time of a vast liberation movement in Africa, several Afro-American musicians made the effort of involving themselves into African music, and try to make a music which would eventually be more faithful to the African roots of jazz. Among them, I suggest you listen to Randy Weston’s Uhuru Afrika (“Freedom Africa”) — also with Olatunji.

For those of you who like to read, I recommend the book by Robin D. G. Kelley, Africa Speaks, America Answers. Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times. The title of that book is also the title of an interesting music album by drummer Guy Warren (which is discussed in the book).

This final piece starts with a beautiful ostinato by James Schenck on bass (played in 5/4), accompanied by the congas of Olatunji and the voice of Abbey Lincoln. At some point, Max Roach’s hi-hat enters the game, and the horns rejoin them by playing a simple melody. Everything sounds like a chant. Then come solos, by Booker Little on trumpet, Walter Benton on saxophone, and Julian Priester on trombone, with backups riffs by the other horns and percussive accompaniment on congas and drums. After a short drum chorus (with percussion), the bass ostinato starts again, and the horns play the main theme, together but in a free way, and the song ends quietly.

It is quite paradoxical that in 1948, at a time where America was starting to dismantle its long-existing segregation laws (that year, Truman published an executive order supposed to desegregate federal administration), South Africa installed its apartheid regime that would last until 1990.

“Tears for Johannesburg”, Max Roach, Freedom Now Suite. We Insist!, 1960

After 5 days of a possibly extenuating music, driven by a clear political message, let’s go to a music which borrows from different roots. In the album It’s Time, recorded in February 1962, Roach gathers a classic sextet (Richard Williams, trumpet; Julian Priester, trombone; Clifford Jordan, tenor sax; Mal Waldron, piano; Art Davis, bass; with Abbey Lincoln on vocals) together with a 16-voice choir (directed by Coleridge Perkinson) he uses as an autonomous instrument.

The present song, “Lonesome Lover”, shows a nice interaction between Lincoln and the choir. It’s a sad love song in a 3/4 tempo.

“Lonesome Lover”, Max Roach his chorus and his orchestra, It’s Time, 1962

An incredible album, where 3 jazz giants unite their forces to create a unique music. We have Max Roach on drums, Charles Mingus on bass and Duke Ellington on piano. While Mingus and Roach are of the be bop generation, Ellington was more than 30 years older, and started playing music at the ragtime era. It’s kind of an old lion and two young cats. For this recording, which the musicians recorded without any previous rehearsal, the pieces were all composed by Ellington — however, Roach and Mingus were only given a bare sketch of the tunes (harmony, structure) together with some visual indications : “crawling around on the streets are serpents who have their heads up; these are agents and people who have exploited artists. Play that along with the music.”

This track, “Money Jungle”, gave the album its name. It’s a blues form, but the way it is played makes it sound much modern.

“Money Jungle”, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Money Jungle, 1962

However, the recording session is known to have happened so badly that at some time, Mingus left and Ellington had to go out and bring him back. Did you know that Mingus had played in Ellington’s big band — until something happened in concert. He and Tizol argued, with racists insults, up to the point that Tizol took out his knife and Mingus chased him with a fire extinguisher. In concert. The next day, Mingus was fired.

More about this in this in this post by Krin Gabbard, author of Mingus’s biography, Better Git It In Your Soul.

50 years later, dummer Terri Lyne Carrington revisited that album with pianist Gerald Clayton and bassist Christian McBride : Money Jungle — Provocative in Blue. It is interesting to hear how they revisit the aggressive playing of Mingus (who pulled onto his bass’s strings so much it sounded like a berimbau). Can you already feel the tune to be played in the drums introduction?

“Money Jungle”, Terri Lyne Carrington, Money Jungle — Provocative in Blue, 2013

This is a not so famous trio recording by Max Roach, with Art Davis on bass and “the Legendary Hasaan” on piano. Hasaan Ibn Ali (1931-1980) was a pianist whose skills and avant-garde gave him some influence among musicians from Philadelphia, up to John Coltrane.

I don’t know well this album, except for this tune whose rhythmic structure is indicated by its title: within a 90 bpm pulse, the tempo is decomposed in various ways, to let you feel a 3/4 tempo, then a 6/8 one, and finally a more classic swing-like in 4/4. The piano chorus keeps the 4/4 rhythmic pulse. There are then an interesting passage where the musicians trade in fours — with a small chorus at the bass.

“Three-Four vs. Six-Eight Four-Four Ways”, The Max Roach Trio, featuring the legendary Hasaan, 1964

We had started this journey in the discovery of Max Roach’s music by a solo drum piece. From that same album, a sextet version of the classic W. C. Handy tune, “St Louis Blues”. Freedie Hubbard is on trumpet, Roland Alexander on soprano sax, James Spaulding on alto sax, Ronnie Mathews o piano and Jymie Merrit on bass. You’ll maybe feel at once that there is a twist with this song: the melody is played in 3/4! However, when the choruses start at 2:25, the musicians go back to the classic 4/4 rhythm, but at a very very fast pace!

“St Louis Blues”, Max Roach, Drums Unlimited, 1965

That’s a solo piece that gave Max Roach’s album it’s name. Compared to the one that opened this musical thread, where the playing was essentially on the snare drum, there’s more hi-hat cymbal playing. The hi-hat is a two parts cymbal which can be open and closed by a foot pedal, and you can also hit the top cymbal with your sticks. When you hit it opened, it resonates, otherwise it doesn’t, and a good coordination allows nice effects. In particular, the first part of the song shows a remarkable virtuosity — maybe it doesn’t sound difficult, but the consistency of the sound, the delicacy of the dynamics are difficult to achieve.

“Drums Unlimited”, Max Roach, Drums Unlimited, 1965

Small step forward, to 1968. Max Roach has formed a new quintet, with Charles Tolliver on trumpet, Gary Bartz on alto sax, Stanley Cowell on piano and electric piano and Jymie Merritt on electric bass.

The sound is more modern, and Roach’s drumming has lost part of his be bop feel. In this track, a composition by Stanley Cowell, the drums do not play purely the role of setting a pulse, it is as if Roach is improvising all the time, playing counterpoint over the melody, or between the silences, and sometimes playing something like a “drum line” that fits well with the bass.

“Equipoise”, Max Roach, Members, Don’t Git Weary, 1968

Sometimes I feel like a Motherless Child A long way from home A long way from my home Believe me, Believe me, Believe me,

In 1971, Max Roach recorded an album with a gospel group led by J. C. White. This is the first track of that album, Lift every voice and sing.

The gospel band has the energy to sing both in front and behind a fierce group of musicians with Cecil Bridgewater on trumpet, Billy Harper on tenor saxophone, George Cables on piano, Eddie Mathias on electric bass.

This track is for y’all, who too often feel like a motherless child, with a special thought for you if that makes you angry.

“Motherless Child”, Max Roach with the J. C. White Singers, Lift every voice and sing, 1971

That version of the famous spiritual has it all, the soul to heal the pain and the force to crumble down the walls that surround us.

The free jazz vibe is not far, nor is the spirit of John Coltrane who had passed away two years before that 1971 recording, still the gospel remains central.

“Joshua”, Max Roach with the J. C. White Singers, Lift every voice and sing, 1971

In 1970, Max Roach founded a band of percussionists : Roy Brooks, Joe Chambers, Omar Clay, Richard Pablo Landrum, Warren Smith and Freddie Waits to play pure percussion music. There is marimba, vibraphone, a musical saw, bells and congs, congas, and, of course, Roach’s drumkit.

This tune, from a live 1973 recording, is a composition by Omar Clay.

To quote a NYT review of a 1986 concert, “The arrangements revealed what percussionists already know - that rhythmic instruments, even such ‘unpitched’ percussion as snare drums and tambourines, have a melodic side, and that there are thousands of ways to be percussive.”

“Onomatopeia”, M’Boom, Re: Percussion, 1973

For two nights of 1975, a band of giants convened at a wonderful “Bop session” and joyfully played the music they had contributed to create more than 30 years before.

Dizzy Gillespie leads the band on trumpet, Sonny Stitt on saxophone, Percy Heath on bass, Hank Jones on piano (John Lewis on some tracks), and Max Roach on drums.

This track is a composition of Dizzie Gillespie. Its title is well deserved!

“Groovin’ High”, The Bop Session, 1975

Each track of the 1973 M’Boom’s recording has been composed by a different musician. This one is a Roy Brooks composition which features Omar Clay on saw and Joe Chambers on xylophone. Max Roach is on timpani.

“Heaven Sent”, M’Boom, Re:Percussion, 1973

A quiet ballad from The Bop Session recorded in 1975. Sonny Stitt has a beautifully sugary sound and Dizzy Gillespie fills in some counterpoint.

“Lover Man”, The Bop Session, 1975

Charlie Parker died on this day, 1955, so why not listening to Max Roach and Parker who had played together since 1945.

This version of Confirmation, a composition by Parker, was recorded in July 1953. With Parker on alto saxophone and Max Roach on drus, we have Al Haig on piano, and Percy Heath on bass. The precision of the syncopation when Parker plays the melody is stunning.

“Confirmation”, Charlie Parker, 1953

This tune is taken from a duet recording with saxophonist Archie Shepp. The album’s title, Force, indicates the political position of the musicians. The longest track is an evocation of Chinese communist leader Mao, the other one protests agains the South African apartheid regime that discriminated black people. The album was recorded during the summer, so presumably after the 16th June uprising where 20000 black students protested and 1500 were killed by the police repression.

“Suid Afrika 76”, Max Roach & Archie Shepp, Force, 1976

At the end of the 70s, Max Roach shared his work between many duo projects and a new quartet, with Reggie Workman on bass, Cecil Bridgewater on trumpet and Billy Harper on saxophone. Tonight, we listen to a live recording by this quartet of a classic Thelonious Monk tune. Especially since its versions by the Miles Davis quintets, this song is often thought of as a ballad, but that was not the way it was initially conceived, and you’ll hear that this version isn’t at all a ballad, but a fiercely driven bop tune.

The first exposition of the melody has nice arrangements between trumpet and saxophone, marked with the quarter-notes riff that started the tune. Bridgewater’s chorus goes on with the bebop style, while Harper’s own chorus has more free jazz influences. Workman’s chorus is stunningly beautiful, with an alternance of abstract passages and reminiscences of the melody. After that, Roach takes his own chorus, in a quite abrupt way, and concludes his dense playing with the classic rhythmic riff that indicates the other musicians to retake the melody.

“Round Midnight”, Max Roach Quartet, Live in Tokyo, 1977

Same concert as yesterday, but a solo piece on the hi-hat. I had already indicated in several occasions how Roach used the hi-hat — this two parts cymbal which is activated on the foot — as an autonomous instrument, and not only a time keeper that would sound on beats 2 and 4, and that’s it.

The only concert of him I attended was around 1994, and as he used to do for all of his concerts, he concluded it with a hi-hat solo. That means he took his hi-hat and his chair, put them on the front stage, and started playing.

This tune is a homage to “Papa” Jo Jones, the drummer of Count Basie’s big band who would start developing the hi-hat as an instrument whose timbre would not be confined to a kind of mute cymbal, expanding at the same time its rhythmic range.

“Mr Papa Jo”, Max Roach Quartet, Live in Tokyo, 1977

An album in duet with South-African pianist Abdullah Ibrahim with a beautiful title, Streams of consciousness. The compositions are attributed to both Ibrahim and Roach. I have no information about how this recording was done, it hears as being improvised on the spot. However, one can recognize patters which are typical from the composition of both musicians. The challenge was to make them fit together.

The tracks of the album are quite long, with the extension of this short piece which starts with a solo by Roach. When the drummer starts playing a systematic groove, the piano enters and adds syncopated chords which slowly turn into a calypso song.

“Inception”, Abdullah Ibrahim & Max Roach, Streams of Consciousness, 1978

Well, it’s already Sunday night here in Europe, but it’s still time to listen to that composition of Max Roach that was recorded in Paris, June 1978. Contrary to the version proposed in It’s Time, a few years before, with musicians and choir, this one is extremely sober. We just have a bass/drums duet. Calvin Hill starts playing the melody on the bass, Roach accompanies him on brushes, and Hill goes on with an improvisation on bass; both trade four, until Hill plays the melody and concludes. Sometimes jazz music projects forward, but this time we are offered a beautifully held back version.

“Sunday afternoon”, Max Roach Quartet, Confirmation, 1978

Yet another duet, in a duet album with Anthony Braxton.

The tune starts with a completely open improvisation by the two musicians, no tempo nor melody seems ascribed. After some time, Roach launches a dense and fast groove and Braxton follows him. Hearing that, I remain puzzled because it is not obvious which musician is guiding the other one, it is as if the two were playing independently, but if you pay attention, you see that they interact. The drum solo that ends the piece is stunning: there are actual melodies beneath the fast pace of drum rolls.

“Birth”, Max Roach featuring Anthony Braxton, Birth and Rebirth, 1979

Let’s continue to listen to that album with Anthony Braxton ! Tonight’s tune is quite different, you’ll see. Roach starts by a short introduction, in which one recognizes classic “roachian” drum patterns (that ta-dada-dadum, ta-dada-dadum, ta-dada-dum…) but he does not fall into them and Braxton starts improvising in an almost bebop style, with a classic bebop drum accompaniment by Roach — a systematic swing pattern on the ride cymbal, and a syncopated counterpoint on the snare drum and the bass drum. At some point, Braxton steps back, the two play more rhythmically than melodically, and Roach ends the track by a solo part.

“Dance Griot”, Max Roach featuring Anthony Braxton, Birth and Rebirth, 1979

This is a composition by Thelonious Monk, revisited by the percussion collective M’Boom in 1979. Quite a challenge when most of the instruments they play are anharmonic. Thanks to Joe Chambers on the vibraphone, and Fred King and Freddie Waits on marimba, we have a melody, but I would like to send a big up to the timpani guys (Warren Smith and Omar Clay) who play with the tension of the skin and produce wonderful effects (the kind of woo-woo tabla players are fond of). Kenyatta Abdur-Rahman is on bells and Ray Mantilla on triangle.

“Epistrophy”, Max Roach M’Boom, 1979

After their 1976 studio recording, Max Roach and Archie Shepp toured in several festivals.

Tonight’s track is taken from a 1979 concert in Austria that was published under the title The Long March. The album contains solo pieces, either by Max Roach or by Archie Shepp, and duet pieces. “The Long March” is one of them, but it is… long, and not really easy listening. This one, “U-Jaa-Ma”, is a composition of Archie Shepp that starts with a powerful syncopated riff using only beats 4 and 1.

The word “Ujamaa” is Swahili for “fraternity”. According to Wikipedia, it was also the name of a socialist ideology that formed the basis of anti-colonial activist Julius Nyerere’s social and economic development policies in Tanzania after it gained independence from Britain in 1961. On the recording of a 1975 concert (in Massy, close to my living place), Shepp translates this word as “Unity”.

You’ll hear what these two musical forces can build out of this political project of “unity” and “fraternity”.

“U-Jaa-Ma”, Max Roach and Archie Shepp, The Long March, 1979

From the same album as yesterday, another duet tune featuring Max Roach and Archie Shepp, bringing a definitely different atmosphere.

The tune starts with the drums only. At some point Shepp enters and brings in a melancholic melody, that sometimes turns into sad shrieks, which Roach sustains with an infectious groove that superposes a rapid flow of non-resonant sixteenth notes using rim shots, a regular hi-hat on beats 2 and 4, and (basically) quarter notes on tom-toms in descending pitches on beats 1, 2 and 3. When Shepp finishes his chorus and lets Roach plays solo, he continues playing the same groove only varying the intensity of the sound, a part I found really beautiful.

There is rage, of course, but there is hope.

“South Africa Goddamn”, Max Roach and Archie Shepp, The Long March, 1979

Let’s listen to Max Roach quartet, still with Odean Pope on flute, Calvin Hill on bass, and Cecil Bridgewater on trumpet. Recorded in 1979, but only published 20 years later in the album Pictures in a Frame, this is a simple waltz, which the musicians play with appealing simplicity. The melody is played by the trumpet, with a beautiful second voice on the flute, and a third one on bass.

“China’s Waltz”, Max Roach Quartet, Pictures in a Frame, 1999

It’s a solo piece, by Max Roach only. A piece he composed and sings and plays at the piano.

The lyrics are taken from an anonymous nursery rhyme, “There was a man of double deed”, which seems to be simultaneously well known and mysterious — nothing makes sense, except for our final death…

Roach turns it into a torchy lament.

“Ode from Black Picture Show”, Max Roach Quartet, Pictures in a Frame, 1999

This is a very long track, more than 30 minutes, composed by Max Roach, recorded in quartet in 1977.

Reggie Workman at the bass starts with a great riff and Billy Harper (tenor sax) and Cecil Bridgewater (trumpet) share the joy of improvising on this melody, while Roach pushes the band with a forceful energy.

After 8 minutes, the mood changes for a bass chorus that lasts 7 minutes, with rare interventions by the trumpet. The drum chorus that follows a second exposition of the theme is full of energy, yet melodic. As often with this quartet, the sax chorus escapes (so it seems, at least) the melody which it recalls occasionally.

A new drum chorus in a different style, using drum rolls to provide long sounds, and toms to infer melodies. The rhythmic structure of the theme can be felt all along, and it’s as if Roach is never bored, nor tired of playing this incredible melody. A last bar, a rim shot, and the musicians give a final version of the theme.

“The Martyr, Pt. 1”, Max Roach Quartet, The Loadstar, 1977

The same album as yesterday, The Loadstar, features this beautiful, heart-rending, slow blues, also composed by Roach, which is so slow that the triplet decomposition of the beat gives a 3/4 feel. As for yesterday, the musicians take the opportunity of playing the tune live to expand it to a long 20 minute piece, so I felt more natural, and maybe more indulging to you, to suggest the 1981 version, in Chattahoochee Red, which lasts only 4 minutes. (Of course, that means you’ll be deprived of a beautiful bass chorus.)

“Six Bits Blues”, Max Roach, Chattahoochee Red, 1981

The album Chattahoochee Red contains pieces of all kinds, and the one that opens the volume is a drum improvisation by Max Roach on top or Martin Luther King Jr’s 1963 speech at the Lincoln memorial, “I Have A Dream”.

After the final “Free At Last”, the quartet goes on with Max Roach’s composition “It’s Time”.

Is there anything more to say?

“The Dream/It’s Time”, Max Roach, Chattahoochee Red, 1981

A free improvisation duet with Connie Crothers, on piano, recorded in NYC, 1982. Born in 1941, Connie Crothers was an American pianist, a student of Lennie Tristano. She recorded a twentieth of albums in the years 1980 up to her death in 2016.

Of course, since this is free improvisation, there’s no apparent melody, no systematic groove. Despite Roach’s constant engagement in avant-garde music, it seems he didn’t involve in that musical form except for that recording. I find interesting that he doesn’t impose his traditional licks, but simply tries to cooperate with Crothers. Discovering that album as I prepare this post, I’ll definitely spend some time listening to her music.

“Symbols”, Max Roach, Connie Crothers, Swish, 1982

A Thelonious Monk ballad, here played by Max Roach Quartet, from the 1983 In the light album.

Anyway, it is essentially Cecil Bridgewater (trumpet) that we hear, with a light drumming on brushes and, especially when the chorus starts, a bass line by Calvin Hill, and to conclude, a second line on saxophone by Odean Pope.

That’s a very humble and melancholic version. Ruby was Monk’s first love.

“Ruby, My Dear”, Max Roach Quartet, In the light, 1983

From the same album as yesterday, let’s listen to a second composition by Thelonious Monk, that time, a fast be bop.

The exposition of the theme is played in relatively classic way, but the choruses definitely take their inspiration elsewhere, already on trumpet and even more on saxophone. Still, Max Roach’s chorus is rigorously built on the structure of the melody, a 12 bar blues, the changes of the melody and its rhythmic patterns.

“Straight No Chaser”, Max Roach Quartet, In the light, 1983

A Live in Berlin album by the same quartet, recorded in 1984. The song is a bop classic, a composition of Juan Tizol, the famous trombone player in Duke Ellington’s band, and also a composer of great songs, of that one, as well as of Caravan.

Nevertheless, the style in which the musicians explore the song is definitely different from the early be bop era. While bass (Tyrone Brown) and drums (Max Roach) provide a consistent and regular groove, trumpet (Cecil Bridgewater) and saxophone (Odean Pope — but the cover says Odeon…) propose kind of a deconstructed version of the classic theme. The second lines are not just here as an ornament, but more as if there were two voices, sometimes in par, sometimes dissonant.

The bass solo is excellent, and when it’s time for a drum solo, it is amazing how Roach uses silence to create expectation.

“Perdido”, Max Roach Quartet, Live in Berlin, 1984

One more piece by M’Boom, from their third album Collage.

It is called Mr Seven because it is based on an infectious 7/8 groove — the composer is Warren Smith.

Max Roach plays vibraphone, Kenyatte Abdur-Rahman is on bass drum and xylophone, Eddie Allen on bell tree, cabasa, cymbal, Eli Fountain on bells, drum and snare, Ray Mantilla on bells, Joe Chambers on marimba, Fred King on timpani, Roy Brooks on tom tom, Freddie Waits and Warren Smith play “various percussion”.

Will you dance?

“Mr Seven”, M’Boom, Collage, 1984

#Jazz #PouetRadio #MaxRoach100

Recorded in 1984, this surprising album “with string quartet” — Christopher Finckel on cello, Louise Schulman on viola, Guillermo Figueroa and Donald Bauch on violin — is a kind of duet for the string quartet seems to sing with one voice, the other being Max Roach’s drums. (The other tracks from that album are solo pieces.)

“Survivors”, Max Roach, Survivors, 1984

In 1984-1985, Max Roach recorded two albums with a string quartet, a double quartet this time: his own jazz quartet (Cecil Bridgewater, trumpet; Odean Pope, tenor saxophone; Tyrone Brown, electric bass), and the Uptown String Quartet consisting of Cecelia Hobbs and John McLaughlin Williams, violin; Maxine Roach (his daughter !), viola; Eileen Folsson, cello.

It seems to me that the writing is more elaborate, that he uses the string quartet in a more structured way that allows the voices of the four strings to develop independently. In any case, this melody, Sis, a composition of Odean Pope, is a beautiful one.

“Sis”, Max Roach Double Quartet, Easy Winners, 1985

From the same double quartet album as yesterday, this is a composition by the trumpet player Cecil Bridgewater that pays homage to the music of Charlie Parker — Bird. In the string arrangement, you can recognize a number of compositions of Parker. (I’m impressed by the vigor of the bass player who plays these quarter notes at high speed — 240bpm — for more than 10 minutes…) After the sax chorus, the string quartet is offered arrangements of Parker songs, and then follows the finale — a drum/percussion chorus — where, once again, the melodic drumming of Max Roach allows to recognize some pieces of Parker.

“Bird says”, Max Roach Double Quartet, Easy Winners, 1985

This track is taken from a two part recording. The first one is a 50 minute suite with the New Orchestra of Boston, and the second one is a shorter song with The So What Brass Quintet — Marshall Sealy on french horn, Steve Turre on trombone, Cecil Bridgewater and Frank Gordon on trumpet, and Robert Stewart on tuba. The absence of harmonic instruments — no piano, no bass — makes that theme a rhythmic feast.

“Ghost Dance”, Max Roach with the So What Brass Quintet

The last recordings of Max Roach contain two remarkable duet concerts, and tonight’s track is taken from one with Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet. It is incredible how both musicians take this classic song as a joyful playground.

From the recording date, 23 March 1989, and the place it was recorded at — Maison de la culture de Saint Denis — I suppose that this concert was part of the Banlieues bleues program that, each spring, proposes concerts of that quality all over the Seine-Saint-Denis. (Neuf-Trois, as people say colloquially.)

(YouTube only proposes the full concert; the link starts at the right time.)

“Salt Peanuts”, Max Roach and Dizzy Gillespie, Paris 1989

Max Roach had already recorded that tune, more than 35 years before, in the memorable 1953 concert at the Toronto Massey Hall. Charlie Parker was on saxophone, Charles Mingus on bass, Bud Powell on piano.

Enjoy these salt peanuts!

“Salt Peanuts”, The Quintet, Jazz at Massey Hall, 1953

The other great concert I was alluding to a few days ago happened in 1995 on the occasion of Mal Waldron’s 70th birthday.

The concert starts with this free improvisation between the two masters.

“Flirtations”, Max Roach and Mal Waldron, Explorations… to the Mth degree, 1995

“Music is like breathing to me. It’s life.” Mal Waldron

“Mistral Breeze”, Max Roach and Mal Waldron, Explorations… to the Mth degree, 1995

Same concert, a ballad composed by the pianist Mal Waldron to the intention of John Coltrane who recorded it in March 1957. In this version, Mal Waldron starts alone, and Max Roach joins him on brushes to end on sticks at the end of the tune. Mal Waldron has written lyrics, which Jeanne Lee rendered magnificently.

“Soul Eyes”, Max Roach and Mal Waldron, Explorations… to the Mth degree, 1995

This is such a great concert.

On a classic theme by Thelonious Monk, these two musicians just play. And laugh!

“Monk’s Dream”, Max Roach and Mal Waldron, Explorations… to the Mth degree, 1995

This is probably the last recording by Max Roach, a 2002 duet album with trumpet player Clark Terry. It seems like these two musicians have blues flowing in their veins. (Only that track is available on YT, alas…)

“Statements”, Max Roach and Clark Terry, Friendship, 2002

“New drum music is made in the culture? Of course, Max Roach is here.”

In 1983, Max Roach met hip hop pioneer Fab 5 Freddy at The kitchen. From be bop to hip hop, Max Roach was there to create groove.

Untitled performance with Fab 5 Freddy, 1983

I wanted to find a copy a of a tune, “Fallen Petals”, that Max Roach recorded in 1999 with his “Beijing Trio”. Since that album does not seem to be available anywhere, let’s go back to 1955 and listen to these Fallen Feathers, composed and arranged by Quincy Jones for the Cannonball Adderley octet.

A gorgeous while simple arrangement of a beautiful ballad.

“Fallen Feathers”, Julian Cannonball Adderley, 1955

A wonderful Clifford Brown composition from the 1954 album led by him and Max Roach.

Each of the choruses is a marvel of musicality.

“Joy Spring”, Clifford Brown and Max Roach, 1954

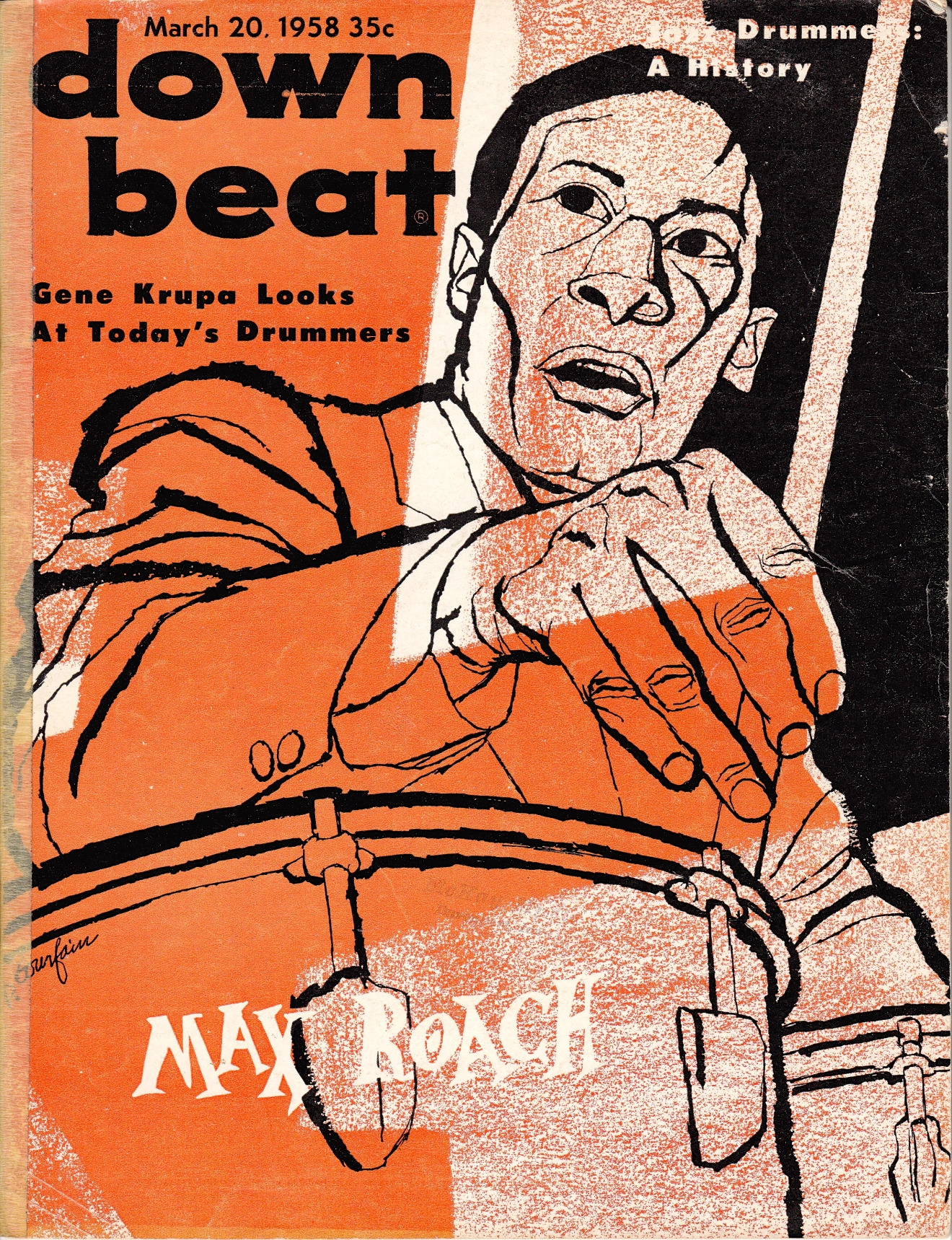

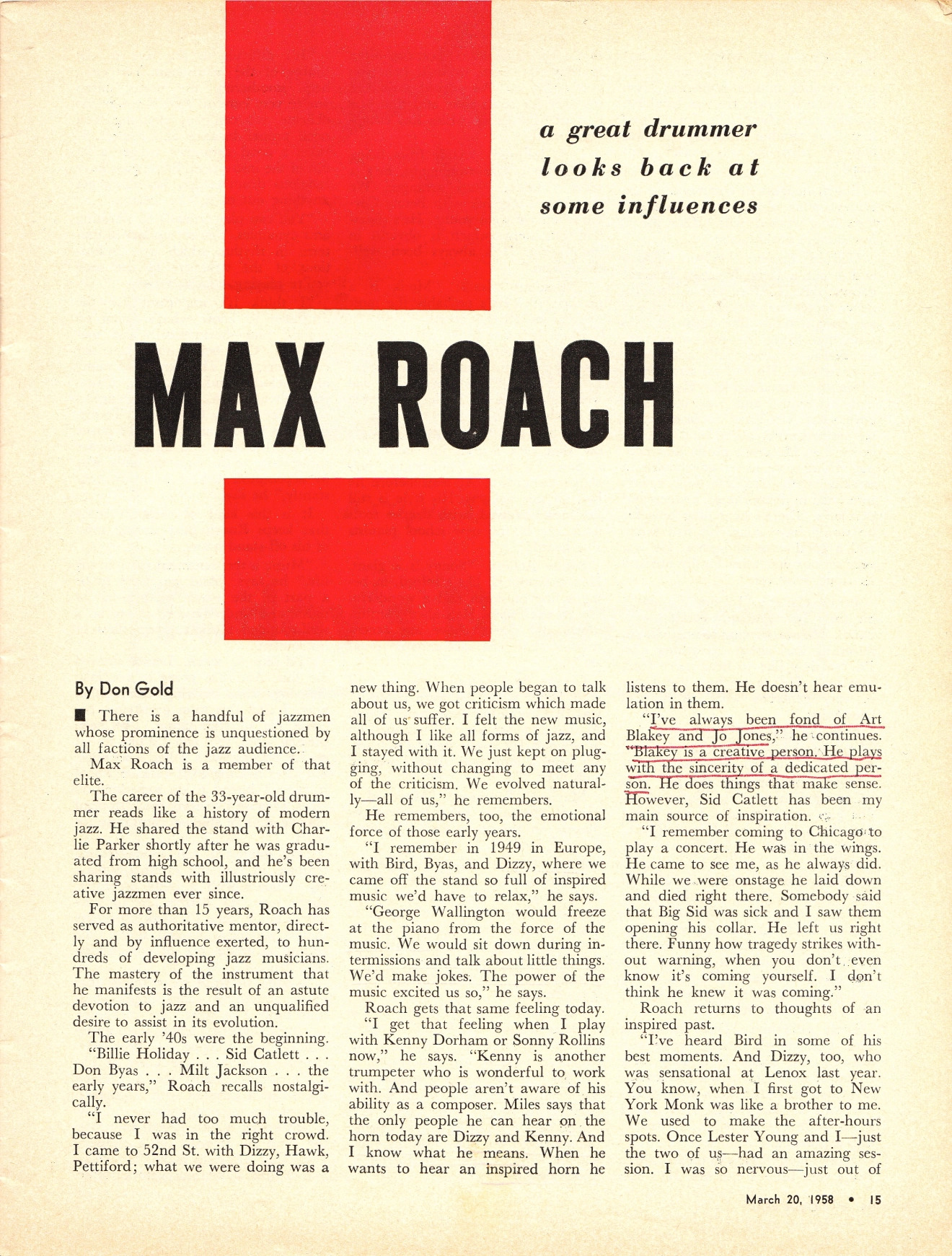

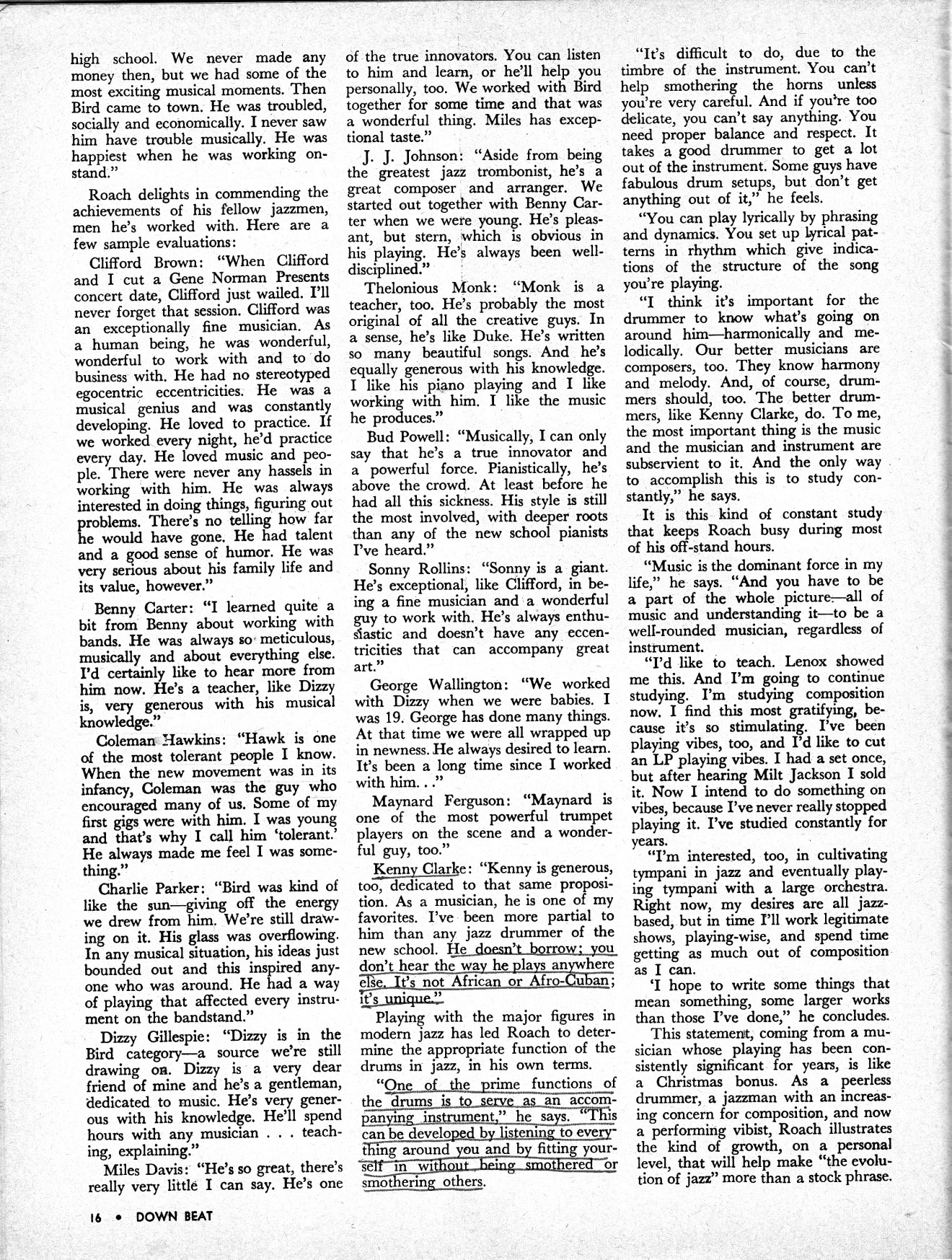

This thread started hundred days ago with a drum solo, and it ends with a drum solo, from the same recording Drums Unlimited. The first one was in 3/4, that one will be in 4/4, a homage from one great drummer to another great predecessor, Sid Catlett, which Roach claimed (in a 1958 Downbeat interview) was his main source of inspiration.

Max Roach builds up an actual melody (Is there a word such as rythmolody?), from repeated motives and variations, arranged differently (such as these two 8th notes that end on the 4th beat, listen how they appear all over the theme, either on the snare or on cymbals). It’s a drum tune that one can sing !

“For Big Sid”, Max Roach, Drums Unlimited, 1965

This file stems out a series of Mastodon threads, that was unthreaded day after day from January 8, 2024 to April 16 2024 on. You can also get it on Markdown or PDF formats.

There is also a YouTube playlist that collects all of these recordings.