April-August 2022

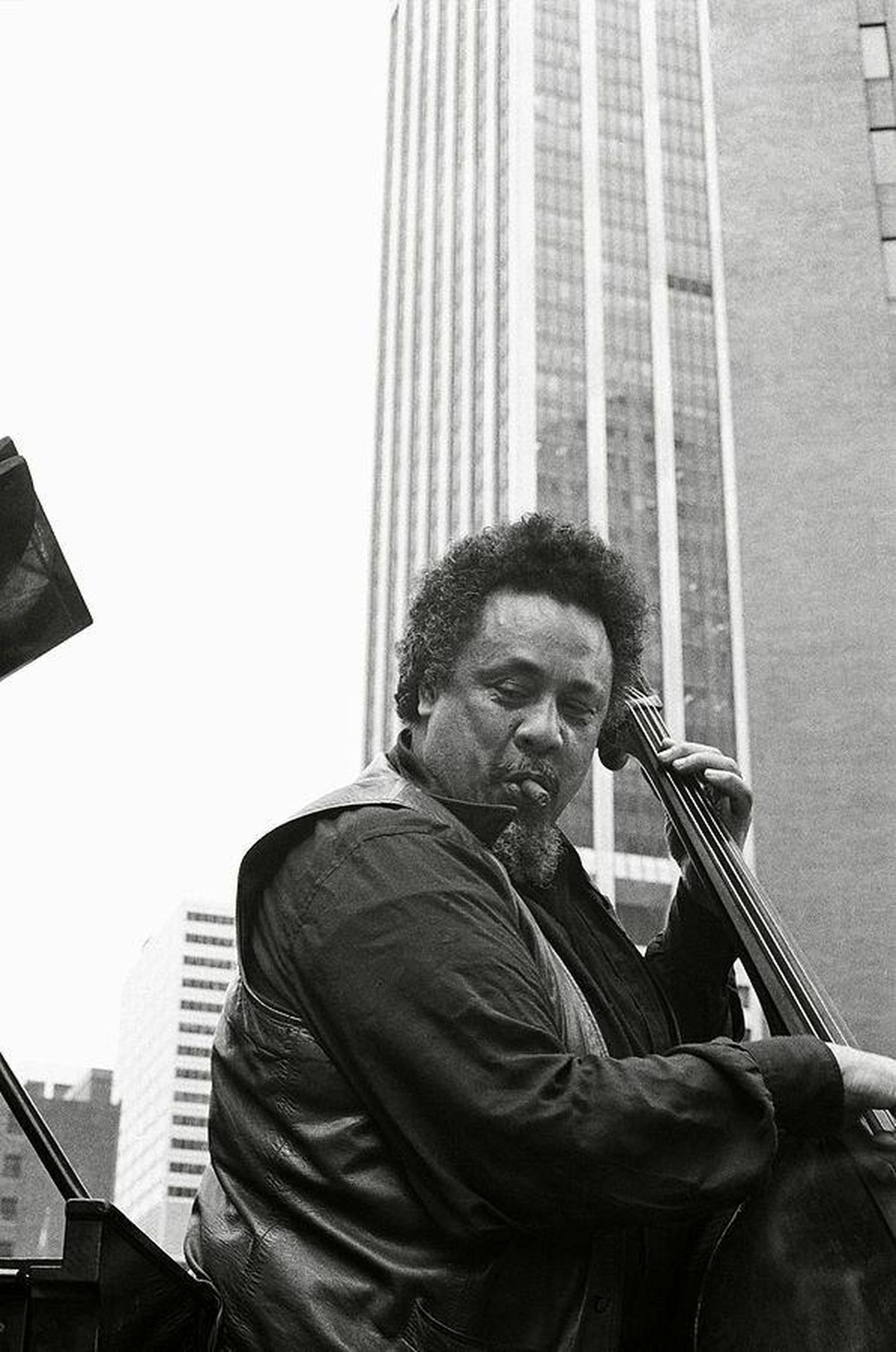

Charles Mingus was born on April 22, 1922, hundred years ago on this day, and he brought to this earth his incredible music, as a bass player, a composer and a band leader, and he also brought an inextinguible desire for justice.

For the forthcoming weeks, I invite you to listen together to the music he played and the one he composed, either played by him, or revisited by other musicians.

Let’s start by putting the bar quite high. A quiet ballad, full of hope and sorrow.

“Goodbye Pork Pie Hat”, Mingus Ah Um, 1959

This composition is from the recording, Mingus Ah Um, one of the many fabulous recordings that was made in 1959. With a beautiful abstract cover painted by S Neil Fujita.

In this recording, Charles Mingus is on bass, Booker Ervin and John Handy on saxophones, Willie Dennis and Jimmy Knepper on trombone, Horace Parlan on piano, and Dannie Richmond on drums.

This song was composed by Mingus as a homage to saxophonist Lester Young (1909–1959), nicknamed Pres (President), who was famous for (playing beautiful music, in particular with Billie Holiday) and wearing this kind of hat, and who had died a few months before the recording.

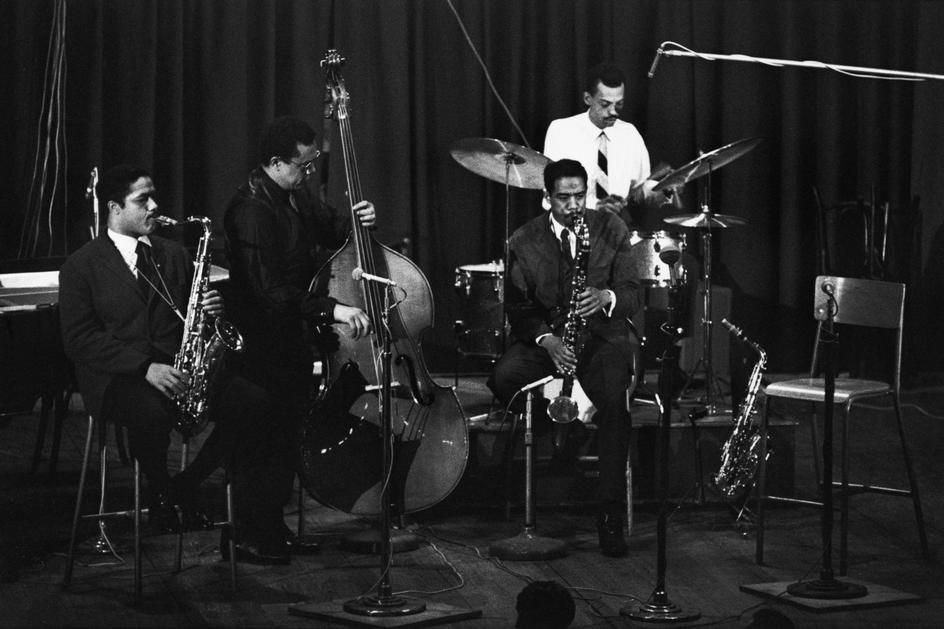

We continue this exploration of Mingus’s music with a live 1953 (May 15th) recording at Massey Hall. This is a great bop quartet, with Charlie Parker on saxophone, Dizzy Gillespie on trumpet, Max Roach on drums, Bud Powell on piano, and Charles Mingus on bass.

“Perdido”, The Quintet — Jazz at Massey Hall, 1953

There is some irony here, because an altercation between Tizol and Mingus, while the two were playing in Ellington’s band. Clearly both of them lost their temper easily, Mingus says he played Tizol’s arrangement one octave higher for that it would sound better, Tizol objected, according to Mingus, racist insults followed, and the legend says that soon the two of them were fighting, Tizol with a knife, Mingus with the fire axe. This is how, a few weeks after he’d been hired by his dream band leader, Mingus was fired by Ellington. You can read more of this story on this Medium article by Krin Gabbard. Mingus recalls his version in his autobiography Beneath the Underdog.

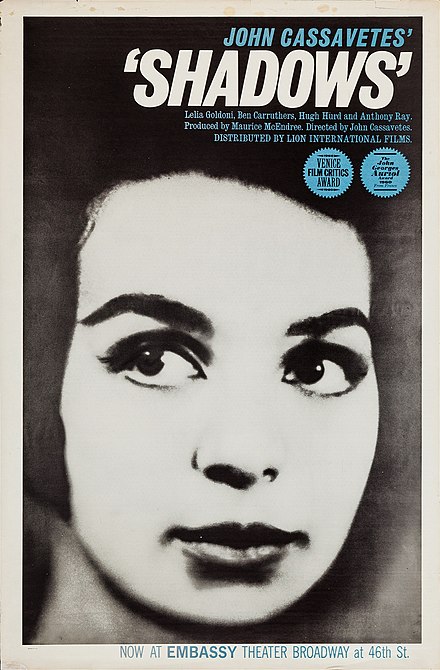

Today, we’ll listen to one of the most famous compositions of Charles Mingus, an almost-a-blues-but-not-quite tune : Nostalgia in Times Square.

This tune has been composed in 1958 and was intended for John Cassavetes’s movie Shadows, for which Mingus improvised music on the improvised acting of the actors. However, that tune was finally removed from the 1959 reworking of the film.

There are many versions of Nostalgia in Times Square, and this live 2008 one explores the bluesy moods of the score. Patricia Barber is on piano, Neal Alger on guitar, Michael Arnopol on bass and Eric Montzka on drums.

(All four play great choruses.)

“Nostalgia in Times Square”, Patricia Barber, Live recording, 2008

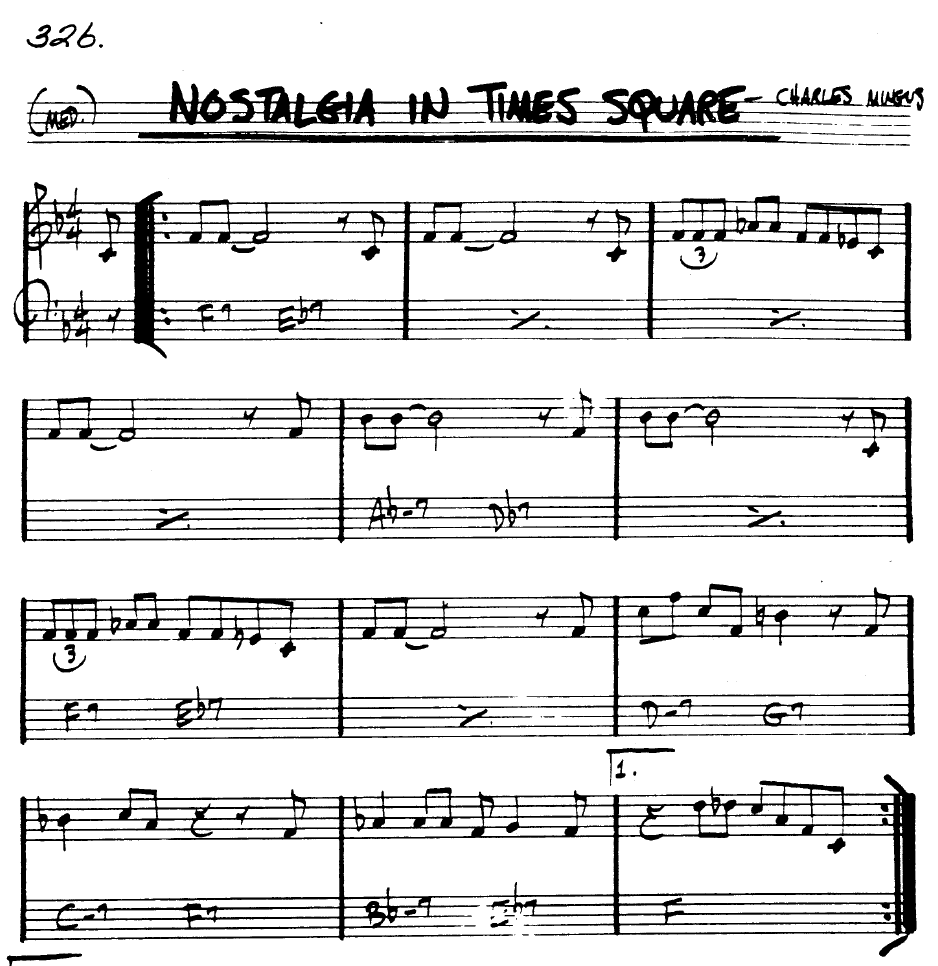

The tune has 12 bars, like all blues, and it starts with 4 bars in F7. But a standard blues would then pass to Bb-7, not to Ab-7, which is why this is not-quite-a-blues. (I owe these explanations to Ron Drotos’s Jazz Pianist’s Ultimate guide to the Real Book.)

A tune with a highly recognizable barytone sax part, originally played by Pepper Adams in the 1959 recording Blues & Roots.

It should not be confused with another tune with the same title that Bobby Timmons had composed for Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers. Although both share a common will of returning to the roots of blues and soul.

The version I propose you to listen to is a 2002 take by the Mingus Big Band, a group of star musicians assembled by Sue Mingus after Charles’s death.

“Moanin’” Mingus Big Band, 2002

(Ronnie Cuber is on barytone saxophone.)

Some people find it too fast, I enjoy its energy and mood.

From his 1957 recording, The Clown, this tune has a form which is typical of Mingus’s compositions, especially the bass introduction, several movements with varied tempos and harmonies, a first one on reeds, wonderful riffs. And blues everywhere.

“Haiti Fight Song”, The Clown, 1957

Jimmy Knepper is on trombone, Curtis Porter on alto sax, Wade Legge on piano, Charles Mingus on bass (of course), and Dannie Richmond on drums.

Mingus would record it once again a few years later, at a faster tempo, under the name “II . B. S.”, an enigmatic title that probably means (says Nat Henthoff), “To Bessie Smith”.

“I was always doing revolutionary things, things that would alert people, so they would stop being so subservient.” — Charles Mingus

The first ten years of his career as a musician, Charles Mingus had recorded many discs as a sideman, under the lead of Illinois Jacquet, Red Norvo, Dinah Washington, Miles Davis, Paul Bley, Charlie Parker and the likes.

Today’s tune is an acknowledgment of Mingus’s role as a bass player, at the service of somebody elses’s music. Recorded in 1951 by Red Norvo’s trio (with Norvo on vibes, Tal Farlow on guitar, and Mingus on bass), a very fast bebop tune.

“Move”, Red Norvo Trio, with Tal Farlow and Charlie Mingus, 1951

This goes very fast, roughly 240 bpm ! and Mingus essentially plays all quarter notes, except that on the theme, you will notice he plays exactly the melody’s rhythm.

This tune is now attributed to the drummer Denzil Best, but it had been recorded in 1949 by Miles Davis in an arrangement by John Lewis, that would be published in 1957 — Birth of the Cool.

The music of Charles Mingus was generally written for medium scale ensembles with a few reeds that allow it to develop a large palette of colors and atmospheres, often within the same piece. It is as if Charles Mingus, whatever he composed, had in mind the sound of Duke Ellington’s orchestra. Do you recall that this band was so dear to his heart, but how he had been fired from it after just a few weeks?

Today’s theme, Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love, is a homage to this orchestra. It was composed in 1974, the year of Duke’s death.

This version is interpreted by a singular and exceptional trio, Paul Motian on drums, Bill Frisell on electric guitar and Joe Lovano on saxophone. This is from their 1998 recording Sound of Love.

“Duke Ellington’s Sound of Love”, Paul Motian Trio, Sound of Love, 1998

Latin America’s musical styles have also been a source of inspiration for Charles Mingus, especially for his 1957 recording Tijuana Moods inspired by a trip to Tijuana. For this recording, he hired the castanets player Ysabel Morel. (For a 1976 live version, Morel helped Mingus finding mariachi dancers.) It is probably to her that this tune was dedicated.

“Ysabel’s Table Dance”, Mingus Big Band, Que Viva Mingus!, 1996

That is a version by the Mingus Big Band, in its 1996 recording, Que Viva Mingus!, which was specifically devoted to Mingus’s latin music.

In 1964, Charles Mingus recorded several concerts he made with his sextet, the first two at Cornell University and at the New York Town Hall, and the other ones in Europe — France, Belgium, Sweden, Germany…

With Mingus himself on the bass, this sextet comprised Eric Dolphy on alto saxophone, bass clarinet, and flute, Clifford Jordan on tenor saxophone, Johnny Coles on trumpet Jaki Byard on piano and Dannie Richmond on drums.

Today’s tune is taken from the Belgian concert, in Liège, April 19th 1964.

“Meditation on Integration”, Charles Mingus Sextet, Live recording (Liège, 1964)

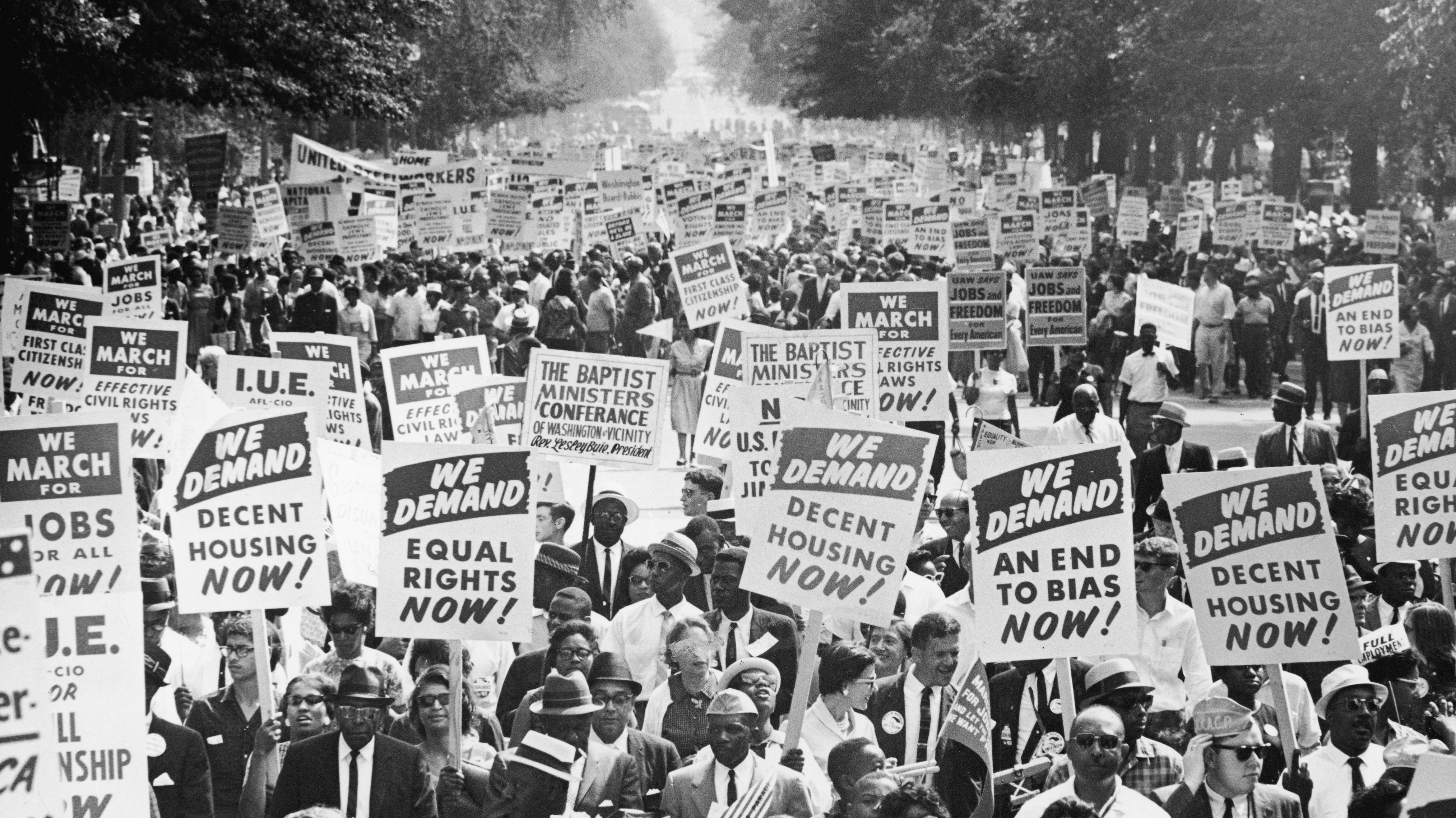

1964 was the year of of the Civil Rights Act that would bring an end to segregation in the United States (which does not mean the story is ended, alas…). The next year, the Selma march and its bloody repression would lead to the Voting Rights Act.

This tune is Mingus’s own reflection on the segregation process. As he said during a German concert (but I can’t find the original text), there are places in Southern US which are similar to concentration camps, only without murder rooms. So Mingus renamed that tune as “Meditations on a pair of wire cutters”, and soon as “Prayer for Eric”.

Indeed, during that European tour, Eric Dolphy announced to Mingus that he would stay in Europe afterwards, but he died in Berlin in June 64, at age 36.

Dolphy’s death is yet another drama of racism. For it seems that he fell into diabetic comma, but when brought to the hospital, they believed — as a black jazz musician — that he was a junkie and left him with the standard treatment for overdose. See that Varsity paper for more of this story.

In the 60s and 70s, Mingus’s bands mostly played music he had composed. But there were some exceptions, and today we shall listen to a rendition by Mingus of a Duke Ellington song, “Sophisticated Lady”.

Mingus has played it in almost all of the concerts of the 1964 series, always in the same form of a bass solo, only slightly accompanied by Jaki Byard on piano. Here is the take from the first concert of the series; it was at Cornell University (Ithaca, New York), on March 18, 1964.

“Sophisticated Lady”, Charles Mingus Sextet, Cornell, 1964

Apart from some hits (such as “Nostalgia in Times Square” or “Goodbye Porkpie Hat”…), I have the feeling that many of Mingus’s compositions have remained quite obscure. The one I chose today was released in June 1979, a few months after Mingus’s death.

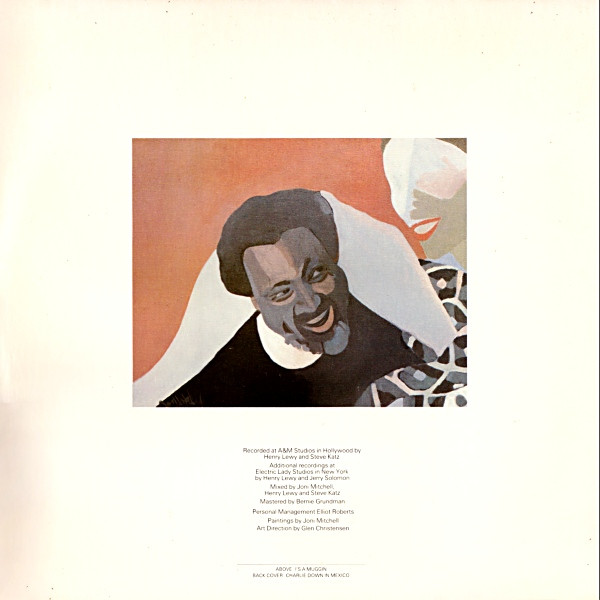

Because of the Lou Gehrig disease that made him pass on Jan. 5th, 1979 he wasn’t able to play bass anymore, and his role as a musician was that of a composer, director, arranger. In 1978, he collaborated with the singer Joni Mitchell.

The initial goal was to make an adaptation of T. S. Elliot’s Four quartets, but that didn’t work out. The recording Mingus regroups a fantastic sextet : Jaco Pastorius on bass, Herbie Hancock on electric piano, Wayne Shorter on soprano saxophone, Peter Erskine on drums, Don Alias on percussion, and Joni Mitchell herself on guitar and voices.

With an always hesitant melody and free interactions of bass, piano and saxophone, this song, A chair in the sky, has a terribly melancholic atmosphere…

“A Chair in the Sky”, Joni Mitchell, Mingus, 1979

Today’s song was played occasionally by Mingus in his concerts (the first known take seems to be in 1962) but has not been published during his lifetime.

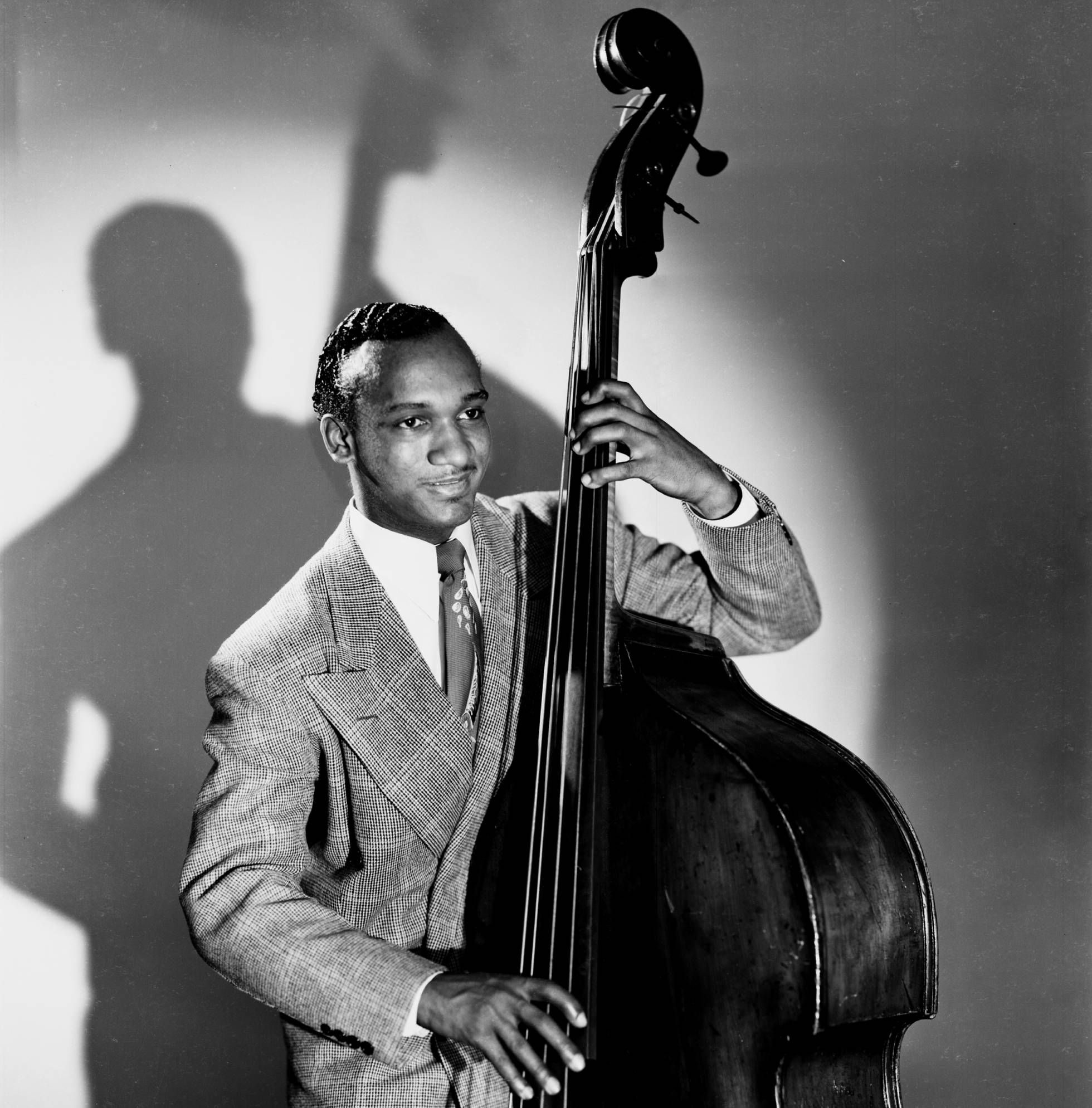

It is a tribute to the great bass player Oscar Pettiford. Oscar Pettiford was born 1922, the same year as Mingus. In the early 40s, he was one of the founders of bebop, with Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, Thelonious Monk, especially during their jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse. Pettiford died in 1960, from a polio-like virus and this composition of Mingus, O.P., has probably been written shortly after his death.

As a homage to one of the bebop founders, it is a very fast tune: the score indicates “Uptempo swing (as fast as possible)” ! Its structure is a bit unusual, AABAC, meaning that the melody has two bridges. The tune was later reworked by Mingus into his big opus “Epitaph”, a gigantic two-hour long piece around history of jazz.

This 1995 interpretation by the Mingus Big Band, is tremendously energetic, and very fast — 260bpm or so. All musicians of the large ensemble concur to a joyous celebration of Oscar Pettiford and his music.

“O.P.”, Mingus Big Band, Gunslinging Birds, 1995

Today’s song is a beautiful swirling melody with an usual structure, its 6 sections have 7, 9, 5, 12, 5 and 6 bars respectively, and it incorporates 5/4 bars to a predominant 4/4 melody, as well as a bossa-nova-like bridge.

“I ought to give titles to my music that make people think.” Charles Mingus said to jazz critic Nat Hentoff once, and today’s one was inspired by his reading of a Ebony magazine article about electrocutions in southern prisons.

Taken from the 1974 recording Changes 2, this song features Charles Mingus on acoustic bass, Jack Walrath on trumpet, George Adams on tenor saxophone, Don Pullen on piano and Dannie Richmond on drums.

“Free Cell Block F, ’Tis Nazi U.S.A.”, Charles Mingus, Changes Two, 1974

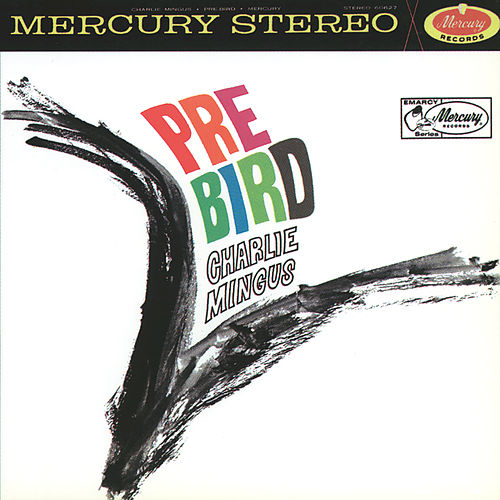

In 1961, Charles Mingus released a big band album that features music that was composed before he had heard Charlie Parker, hence the title of this album, Pre-Bird. Part of the tracks are compositions by Charles Mingus himself, but we will listen to another one!

Let’s listen to the first track of the recording, a well known 1939 composition of Billy Strayhorn, immortalized by Duke Ellington, and also sung by Ella Fitzgerald and many other singers : Take The A Train.

“Take The A-Train”, Charles Mingus, Pre-Bird, 1961

The piano introduction is characteristic (Paul Bley is on piano!), and the energy of the band is entertaining. But take care of the arrangement: do you notice what happens when they repeat the second phrase at 00:10 ? (Hint: put headphones on.)

On the left side channel, the musicians repeat the second phrase, but on the right side one, they play something else: another tune starts there, the 1930 Jimmy Hugh tune, “Exactly Like You”.

There are great solos by Paul Bley (piano), Eric Dolphy (alto saxophone), Jimmy Knepper (trombone), Booker Ervin (tenor saxophone), supported by a fantastic arrangement and the infatigable rhythm section of Charles Mingus and Dannie Richmond.

The last rendition of the melody is also remarkable, where the two melodies intertwine nicely, the piano introduction is added as a riff, and everybody lands off with the standard “Take the A train” ending, as it should.

In 1963, the barytone saxophone player Pepper Adams reunioned a group of musicians to record a disk of Charles Mingus compositions. Paul Chambers or Bob Cranshaw hold the bass, Hank Jones is on piano, and Danny Richmond on drums. But also an excellent horns section: Zoot Sims, on tenor saxophone, Charles McPherson on alto saxophone (he would soon replace Dolphy in Mingus’s sextet), Bennie Powell on trombone, Thad Jones on piano. And of course Pepper Adams on baritone saxophone.

Remember? We had already encountered Pepper Adams when we listened to Mingus’s composition “Moanin’”, from the 1959 recording Blues and Roots.

The tunes were selected jointly by Mingus, Adams and vibist Teddy Charles, and some of the arrangements (by Thad Jones or Adams, or Charles) depart from what Mingus himself had done.

And this track, “Carolyn”, has been written especially by Charles Mingus for this album in tribute to his daughter Carolyn Keikki Mingus.

I hope you’ll enjoy its mixture of latin/swing feeling.

“Carolyn”, Pepper Adams, Plays compositions of Charlie Mingus, 1963

This tune doesn’t seem to have been often recorded, it appears on Mingus’s Pithecanthropus Erectus and Reincarnation of a Love Bird from 1971 and 1974, but I chose this 2002 version from the Mingus Big Band, with an arrangement of Sy Johnson.

“Love is a Dangerous Necessity”, Mingus Big Band, Live recording, 2002

The two long choruses of Craig Handy on tenor saxophone and of Johnathan Blake on the drums show how far the music can be pushed to thanks to the musicality and energy of these cats… Also, at the beginning of Blake’s solo, look out how Boris Kozlov’s line on the bass does give the impression that the time will stop, and how this makes Blake smile.

This is a song that Mingus wrote for his first wife, Celia, although they had apparently already divorced when the song appeared in the recording The Clown. This was actually the first blues that Mingus recorded. According to Mingus, it was also written to prove some jazz critics that he could swing.

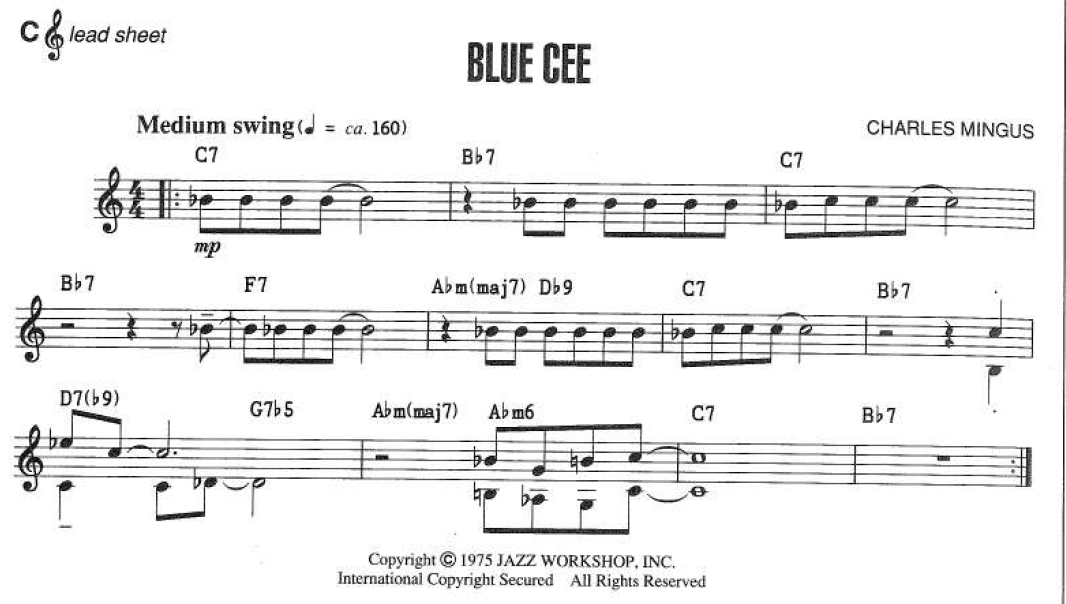

“Blue Cee”, Charles Mingus, The Clown, 1957

In 1952, it was with Celia (and drummer Max Roach) founded the Debut Record company. After her divorce with Mingus, Celia would marry music and film producer Saul Zaentz with whom they would have great success thanks to the band Creedence Clearwater Revival, or the Amadeus movie.

There is a pun in the title of the song. Cee refers to Celia, also, but also to the fact that this is a blues in C. Also, its writing is similar to Duke Ellington’s C Jam Blues : a tune built on the repetition of a note, but here, it is a Bb that resolves to C, not a G.

The band’s composition is a bit unusual: piano, bass, drums, alto saxophone and trombone. (I love how the initial repetition of the melody is done by the trombone, while the saxophone plays some chorus under it.) Mingus’s chorus is remarkable.

In the first years of his career, Charlie Mingus was a selected accompanist, and he played as a sideman in great bands such as those of Illinois Jacquet, Louis Armstrong, or Howard McGhee. For today, let’s listen to a track recorded in December 1945. Charles Mingus takes the bass in Lucky Thompson’s band and Dinah Washington sings this “Blues for a day”. (This is Milt Jackson on vibraphone, Gene Porter on clarinet, possibly Lucky Thompson for the sax).

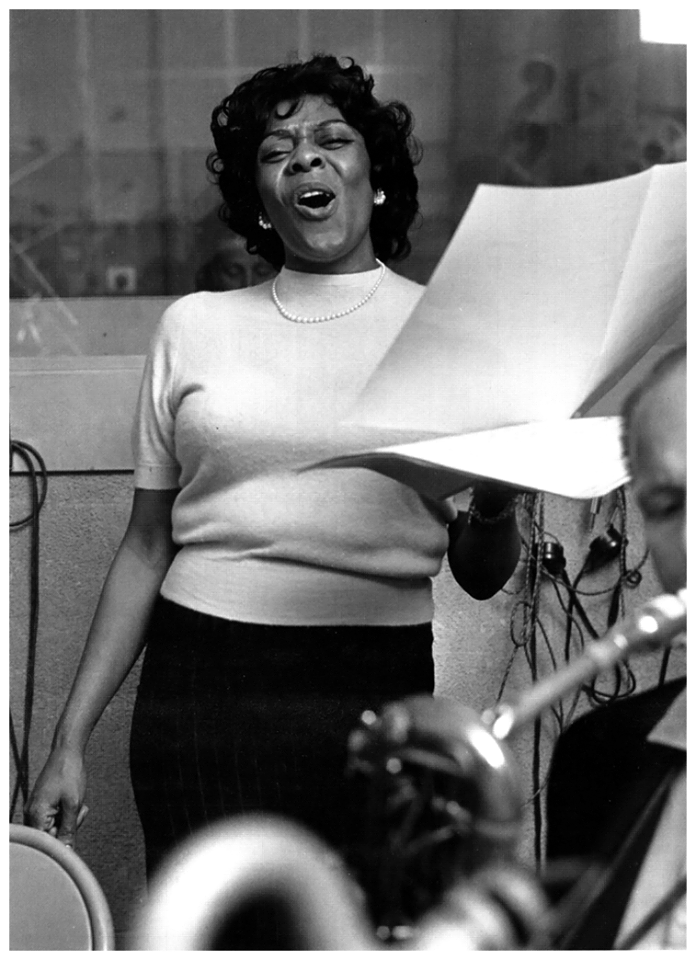

“Blues for a Day”, Dinah Washington with the Lucky Thompson orchestra, 1945

There’s so much sadness in those lyrics…

Today’s tune is a sumptuous ballad from Mingus’s classic Mingus Ah Um, but in a recent version, by Ravi Coltrane’s quartet. Accompanying Ravi Coltrane on tenor saxophone, we have Darry Hall on bass, George Colligan on piano, and Steve Hass on drums.

“Self Portrait in Three Colors”, Ravi Coltrane Sextet, Mad 6, 2003

And while you listen to this beautiful song, you can read Charles Mingus’s own words, the one with which he starts his autobiography, Beneath the Underdog, and then trying to discern the underlying three colors…

— In other words I am three. One man stands forever in the middle, unconcerned, unmoved, watching, waiting to be allowed to express what he sees to the other two. The second man is like a frightened animal that attacks for fear of being attacked. Then there’s an over-loving gentle person who lets people into the uttermost sacred temple of his being and he’ll take insults and be trusting and sign contracts without reading them and get talked down to working cheap or for nothing, and when he realizes what’s been done to him he feels like killing and destroying everything around him including himself for being so stupid. But he can’t—he goes back inside himself.

— Which one is real?

— They’re all real. — The man who watches and waits, the man who attacks because he’s afraid, and the man who wants to trust and love but retreats each time he finds himself betrayed. Mingus One, Two and Three. Which is the image you want the world to see? — What do I care what the world sees, I’m only trying to find out how I should feel about myself. I can’t change the fact that they’re all against me – that they don’t want me to be a success. — Who doesn’t? — Agents and businessmen with big offices who tell me, a black man, that I’m abnormal for thinking we should have our share of the crop we produce. Musicians are as Jim-Crowed as any black motherfucker on the street and the … the … well, they want to keep it that way.Charles Mingus, Beneath the Underdog

A long tune written for a big band concert at Lincoln Center (New York City) that took place on February 4, 1972, with an incredible line-up.

The song was written for Roy Eldridge, but the old trumpet player (born 1911) was sick and couldn’t make it for the concert. He was apparently replaced by the young Jon Faddis (only 18 at the time of the concert)!!

Today’s version is the one by the Mingus Big Band, recorded in 1999 in the album Blues and Politics. As for the 1972 concert, the arrangement is due to Sy Johnson.

“Little Royal Suite”, Mingus Big Band, Blues & Politics, 1999

The tune has many parts. Listen how it starts with drums and trumpet… and then goes on with a quiet ballad with the lead on trumpet (probably Earl Gardner). At some points, the tune has a latin feel, with an even pulsation on the cymbal (almost a samba on the bass at 7:04). Something else, definitely post-bop-big-bandish starts at 7:50, with saxophone chorus. And around 12:00, it resolutely turns into an unmistakable blues. At the end of the tune, trumpet, sax and baritone sing the same tune in a remarkable 3-voice arrangement.

Mingus’s music is full of rage, and the reason for that rage is racial injustice, in its strongest terms.

does he sing on the opening of today’s song, “Fables of Faubus”.

“Original Faubus Fables”, Charles Mingus presents Charles Mingus, 1960

And this tune has a racially charged history.

It was written as a direct response to words of the Arkansas governor Orval Faubus who was refusing the integration of nine black teenagers at Little Rock Central High School. Let me quote Wikipedia’s Little Rock Nine article: After “several segregationist councils threatened to hold protests at Central High and physically block the black students from entering the school, Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists.”

The situation was temporally resolved by President Eisenhower who federalized the entire 10,000-member Arkansas National Guard, taking it out of Faubus’s control, and the nine students could attend school — under protection of the army. See this Life online photo gallery.

These students had a difficult year.

They were assaulted, they were hurt.

But that was not the end of it, since Faubus simply had the public schools closed in 1958. Only in 1959 could the crisis come to an end.

[Little Rock, 1959. Rally at state capitol Photographer: John T. Bledsoe (http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppmsca.03120)] (images/Faubus1959.png)

In 1959, Mingus recorded a first version of the song for his album Mingus Ah Um. But Columbia refused that they say the words he had written, so that version was an instrumental one. And because of legal reasons, the title of the song had to be changed when Mingus recorded it in 1960 for the new Candid company founded by Archie Bleyer and directed by the jazz writer and civil rights activist Nat Hentoff.

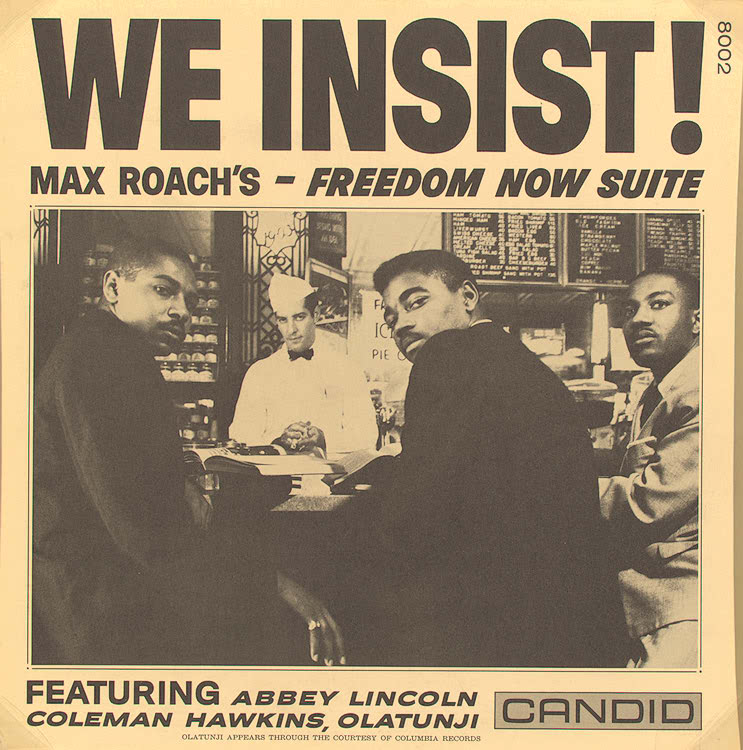

That same year, Candid published another notable jazz recording by drummer Max Roach and singer Abbey Lincoln : We Insist! containing their “Freedom New Suite.”

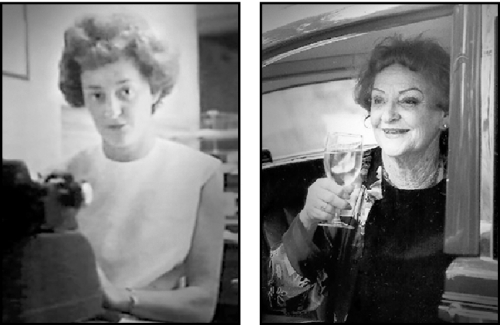

Even Mingus and Roach, those two musicians filled with rage and desire for more justice, could wish for a simple relaxed mood. And they provide the rhythm section for this superb recording of Hazel Scott.

I didn’t know who was Hazel Scott. And I must confess that, unknowing of Anglo-saxon first names (nor of the heir of Julia Roberts or Emily Blunt), I hadn’t realized that Hazel was the first name of a woman. And what an extraordinary one!

Born 1920 in Trinidad she moves to New York City with her mother in 1924. A child prodigy, she can play whatever music she hears, and she becomes at 8 the private pupil of a Julliard school professor. In 1940, she becomes a movie star but refused 4 roles in row, because she would have to play a “singing maid, and as a Black woman — and an educated, classically trained musician — she resented the racist overtones of such parts. She even demanded equal pay to her White counterparts.” (From a Washington Post paper).

She had had to fight segregation. In 1945, reiterating what they had done for Marian Anderson in 1939, the “Daughters of the American Revolution” refused that she plays in Constitution Hall.

In 1950, she is the first African-american woman to have her own show on TV. There she performed with Charles Mingus and Max Roach. Today’s recording is a tune from the 1955 recording that Scott would do with Mingus and Roach. This is a superb piano trio recording. Among all these beautiful tunes, I propose you to listen to a composition of Scott herself, “Peace of Mind”.

“Piece of Mind”, Hazel Scott with Max Roach and Charles Mingus, relaxed PIANO moods, 1955

In 1950, her show came to an abrupt end when she had to face McCarthyism. “We should not be written off by the vicious slanders of little and petty men,” she said to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. That did not help her and she moved to France from 1957 to 1967.

Two days ago, we were listening to Fables of Faubus, the original version, with lyrics. And as iconic of Mingus’s music this song is, it was to be played by other groups of musicians. So it’ll make some good to listen to it a few more times. For tonight, it’ll be a version by the pianist Ran Blake. This is a 1969 solo recording, with a funny title — Blue Potato & Other Outrages. It seems to start smoothly, but in the end the irony and rage emerge too.

“Fables of Faubus”, Ran Blake, Blue Potato & Other Outrages, 1969

I would like to propose yet another version of Fables of Faubus. Those of you who are attentive might have discerned the rule that I follow for choosing interpretations and pardon me for slightly diverging from this rule today. Still, this will be a big band version.

Eleven musicians, ten horns and an accordion, revisit Mingus’s music and kind of free it from the arrangements that now sound familiar, too familiar maybe since most of the recordings of Fables of Faubus are built on the original Sy Johnson’s arrangement.

“Fables of Faubus”, Tá Lam 11, Mingus!, 2011

No bass, then, and no drums neither. The whole band is lead by Gebhard Ullmann (on bass clarinet), but I had been attracted by Daniel Erdmann’s name on the cover — he his a member of the astonishing trio Das Kapital (saxophone, electric guitar, drums).

I am certain this will lead you to unsuspected places.

For tonight, that’ll be a live recording of Mingus’s quintet, one evening of January 1959. John Handy and Booker Ervin play alto and tenor saxophones, Richard Wyands is on piano, Dannie Richmond on drums, and Charlie Mingus on piano.

The tune has almost the same title as a lively 1951 waltz by Fain/Hilliard that I love pretty much, and of which Bill Evans’s trio (with Scott LaFaro and Paul Motian) made a thrillingly melancholic version in 1961.

But this “Alice’s Wonderland” is a Mingus composition, whose title has also been “Diane” — but don’t confuse with the beautiful (and equally melancholic) Rapee/Pollack tune recorded by Paul Bley and Chet Baker in 1985.

Mingus wrote in the liner notes for his live “Wonderland” recording : “It may be the prettiest thing I ever wrote—a girl trying to make it in this big rough world, like I am. I try to show her sadness (the alto on top) but also her strength in her art and in her conviction in what she believes in (the tenor on the bottom) even if there are harsh, unresolved parts of her life. She was a painter I knew. It was written for her because I loved her at one time.”

“Alice’s Wonderland”, Charles Mingus, Wonderland, 1959

Today, let’s listen to a 1930 composition of Johnny Green, with lyrics by Heyman, Sour and Eyton : Body and Soul. A wonderful ballad, one of my favorite tunes.

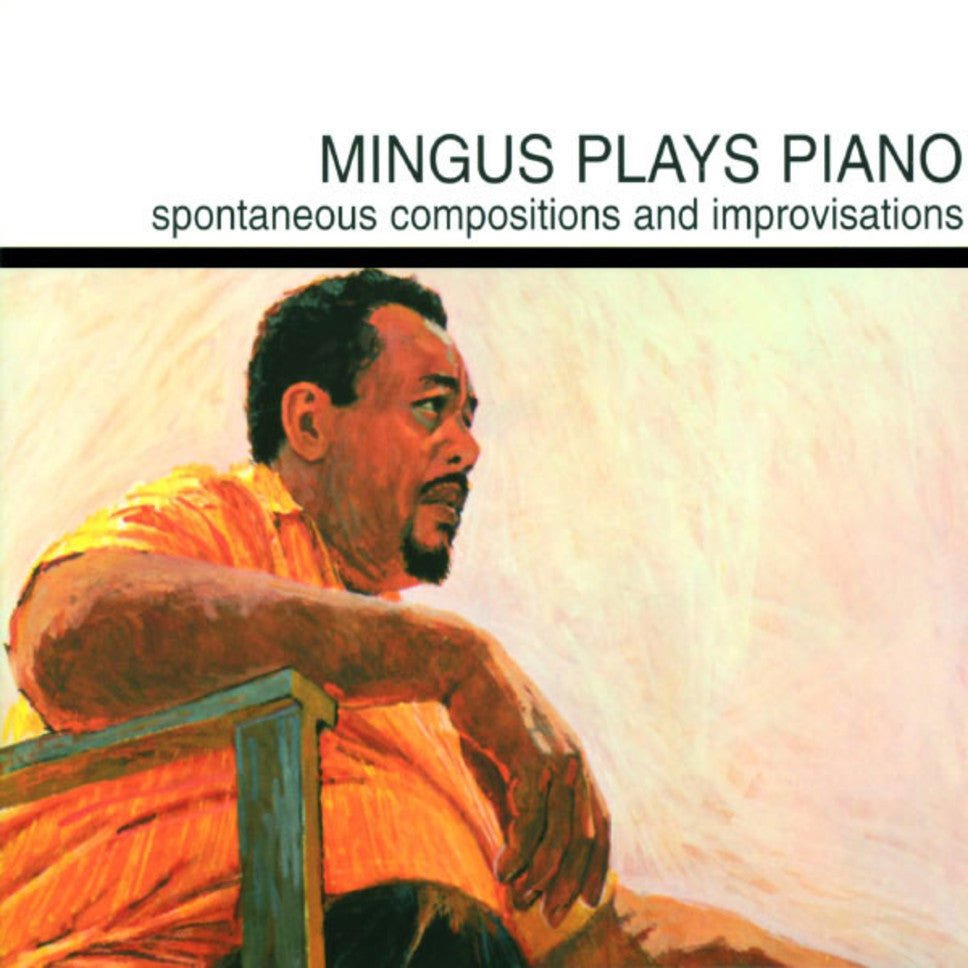

This version is definitely unique in Charles Mingus’s discography. — No large ensemble, no bass neither : he’s alone at the piano. That was recorded in 1963.

The quietness of this version should not abuse you. In his biography of Mingus, Gene Santoro tells us that this happened at quite a troubled time of Mingus’s life. The big loft he was trying to set up to host musicians — and music — had to close, because “fire department inspectors wanted the floor reinforced, which would cost six to eight thousand dollars. And the neighbors complained about noise!” Nevertheless, “he was up every night, playing the piano. He told Bob Thiele he wanted to record a solo piano disc, but he was nervous. It wasn’t like being onstage, or at home. On July 30, 1963, he recorded eleven tunes at RCA Studios.”

That recording became Charles Mingus plays piano, spontaneous compositions and improvisations, a combination of free interpretations of jazz standards and of compositions.

It seems the first recording of this song, “Eclipse” was 1953, in a vocal version sung by Janet Thurlow.

Mingus wrote he had sent the tune to Billie Holiday, but didn’t know whether she received it. He says he figured she could sing it because he had heard her sing Strange Fruit.

Here, in a free interpretation by Judy Niemack and Mal Waldron, from a 1994 recording dedicated to the music composed by Mingus, Monk and Waldron himself.

“Eclipse”, Judy Niemack and Mal Waldron, Mingus, Monk and Mal, 1994

Another version of “Eclipse”, this time recorded in 2002 by the Mingus Big Band, so without lyrics, but a much richer orchestration and a latin feel.

“Eclipse, Mingus Big Band, Tonight at noon…, 2002

This was a recording of Mingus I didn’t know anything until Thomas R. told me about it last friday. So let’s listen to something from it. Oh Yeah !

Charlie Mingus is with a band of fellow musicians, Book Ervin on tenor saxophone, Jimmy Knepper on trombone, Dannie Richmond on drums, the great Rahsaan Roland Kirk on a lot of horns (flute, siren, tenor saxophone, manzello and strich), Doug Watkins on bass… what?

Yes, Watkins on bass. Because Mr Charlie is on piano and vocals. You’ll see he is a great pianist, and his deep raucous voice makes great intros for this recording which is infused with the soul of blues.

Devil Woman

“Devil Woman”, Charles Mingus, Oh Yeah, 1962

Now’s the time to listen to some recording of Charlie Mingus. And standing next to Mingus, on that night of 1953, Art Taylor on drums and John Lewis on piano, as well as 4 trombones ! — J.J. Johnson, Bennie Green, Kai Winding and Willie Dennis.

Composed by Charlie Parker, this tune has become a standard.

“Now’s The Time”, Charles Mingus, Live at Putnam Central Club, 1953

(Order of the trombone choruses : J.J. Johnson, Bennie Green, Kai Winding and Willie Dennis)

Charlie Parker — Bird — is an anchor for every modern jazz musician. Initially a devotee of Duke Ellington’s music, it is apparently to Mingus’s wife Celia that we owe his recognition of Parker’s music. Remember the title of that disc, “Pre-Bird”, Mingus had recorded, with music that was composed before he had ever listened to Parker’s music ?

So that title, “Reincarnation of a Lovebird”, is really about reviving Charlie Parker’s music, in Mingus’s own style.

“It has a little bit of what Charlie Parker did, but usually when I write something about Monk or Bird, I’m not trying to write the way they write, I just write my interpretation of my feeling for them and their feeling for me. As for the name, I was doing a benefit for Bird at Carnegie Hall and somebody said they saw a feather fall. I wrote a poem about that.”

We shall listen to Mingus’s original recording once, with its introduction built up from many Parker’s phrases, but for tonight, I propose this melancholic version by Steve Lacy on soprano saxophone and Gil Evans on electric piano.

“Reincarnation of a Lovebird”, Gil Evans/Steve Lacy

Yes, this is the Gil Evans, pianist, composer, arranger, band leader, who worked with Miles Davis and many other musicians. He was born 1912, just ten years before Mingus, and coincidentally died in Cuernavaca (Mexico), the same place as Charlie Mingus.

Born in 1934, the saxophonist Steve Lacy was younger. Initially into dixieland, his meeting with Cecil Taylor pushed him to free jazz, and to Monk’s music. This recording was made in Paris, 1988, where the saxophonist Steve Lacy was living since the beginning of the 70s.

This is a 6/4 piece, six beats per bar, which Mingus composed for Columbia in 1959. He wanted to give this tune the same feeling of a former piece which Atlantic hadn’t published.

Around the same time, Cannonball Adderley released “This Here”, which had eventually more success.

Today’s version is not by the Mingus Big Band (like I had planned to—the version on YouTube seems to be another tune), but by the Woody Herman Big Band. It was recorded in 1979 at Monterey, a few months after the death of Mingus.

Here it goes!

One, two, three… One two three…

“Better Get Hit In Your Soul”, Woody Herman Big Band, 1979

The style is not as round as it was 10 years before, jazz-rock influences can be felt, it may be a bit too fast for my taste, but with Stan Getz, Dizzy Gillespie, Slide Hampton on the horns… I thought you had to listen to this! Let you energize by it!

An homage to Thelonious Monk built on a syncopated descending phrase and a puzzling 8-bar collective improvisation passage in section A.

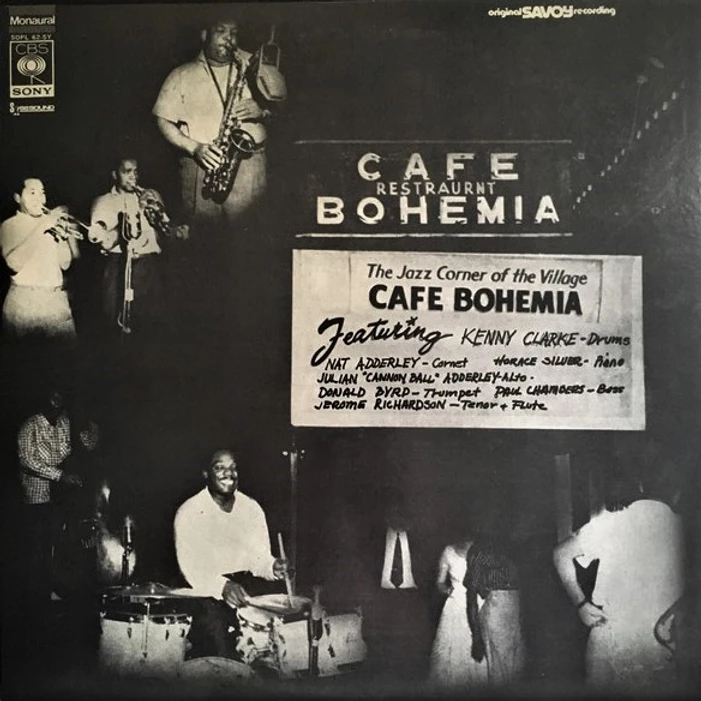

It was recorded live at the Cafe Bohemia on Dec 23, 1955. (There are two discs made from this session.) George Barrow is on tenor sax, Eddie Bert on trombone, Mal Waldron on piano, Charles Mingus on bass and Willie Jones on drums.

“Jump Monk”, Charles Mingus at the Café Bohemia, 1955

“It’s not supposed to sound like Monk. I liked him. I don’t think it sounds like anything he’s ever done. The reason I called it ‘Jump’ is because Monk was always moving around.”

The Cafe Bohemia was a bar and restaurant place in New York City who became a jazz place for a few years (1955-1960), after Charlie Parker proposed to play in exchange of drinks he hadn’t been able to pay. However, he died on March 12 and didn’t made the gig.

This website has some history of this club and the music that it gave birth to, thanks to its “progressive jazz only” policy. Basically all big cats of that era, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Cannonball Adderley, Oscar Petitford, Kenny Clarke…

In the Dec 23 1955 gig at Cafe Bohemia where Mingus’s band played that Jump Monk, they also played some standards.

That one is a composition of Tadd Dameron : “Lady Bird”.

The exposition of the theme sounds like if it is a Mingus theme, with large changes in the dynamic, but the choruses are closer to the hard bop style. You’ll note the drums chorus by Willie Jones, with added spice from the horns.

“Lady Bird”, A night at Café Bohemia, 1955

Tadd Dameron (1917-1965) was a pianist, arranger, composer in the bop style. We owe him many standards, such as this “Lady Bird”, “If You Can See Me Now”, “Hot House”, “Good Bait”…

A few days ago, we had listened to a track from the 1962 Oh Yeah album. And as Thomas R. had told me, one of the tracks of that album has a terrible title

Definitely a blues.

Today’s version acknowledges that blues, rythm’n blues and rock’n roll are sisters in faith (to the Lord of Music). It is extracted from a recording produced by Hal Willner: Weird Neightmare — Meditations on Mingus.

Bill Frisell is the main guitar player in that recording, but the track I have chosen goes further afar since this is Charlie Watts on drums, Keith Richards on guitar and vocals, Chuck Leavell on piano. Oh Yeah!

By the Mingus Big Band, in their Blues and Politics recording. (special dedication to all antifascists)

The tune starts with a spoken text, only accompanied with heartbraking horns.

One day they came and they took the communists, and I said nothing because I was not a communist. Then one day they came and they took the people of the Jewish faith, and I said nothing because I had no faith. Then one day they came and took the unionists, and I said nothing because I was not a unionist. They burned the Catholic churches one day, and I said nothing because I was a Protestant. One day they came and they took me, and I could say nothing because I was as guilty as they were of genocide, destroying the rights of any man to live.

As you may have guessed, the lyrics are inspired by a famous predication of Martin Niemöller, a German pastor who survived the nazi concentration camps and devoted his life to peace. However, the exact text is kind of lost.

Mingus had first performed that song at the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1965. We still have to fight so that racism, violence and hate do not happen here, nor anywhere.

“Don’t Let It Happen Here”, Mingus Big Band, Blues and Politics, 1999

A strange tune, mostly swinging, with small passages in 6/4 with a latin feel. It was first played at the Village Vanguard in 1973, under the title “No Name”, and published in the album Mingus Moves.

Don Pullen is on piano, George Adams on tenor saxophone, Ronald Hampton on trumpet, Dannie Richmond on drums, and Charles Mingus on bass.

“Opus Four”, Charles Mingus, Mingus Moves, 1973

Sometimes, the composition is credited to George Adams, who started to work with Mingus at that time. After Mingus’s death, Adams, Pullen and Richmond would be part of a quartet (with Cameron Brown on bass).

I should add a thread someday about the drummer Dannie Richmond whose collaboration with Mingus encompassed more than 20 years. Clearly, all the variations of rhythm and tempo which are prevalent in Mingus’s music wouldn’t have worked without a drummer like him.

This 1941 song is often played in a very romantic mood. In today’s version, recorded at Antibes in 1960, the Mingus sextet plays it quite fast, with dissonances and rhythmic variations…

Bud Powell is on piano, Dannie Richmond on drums, Booker Ervin and Eric Dolphy on saxophones, Ted Curson on bass, and Charlie Mingus on bass.

“I’ll Remember April”, Charles Mingus, Live at Antibes, 1960

The very long piano chorus of Powell is interesting, of course, listen him singing what he plays with a raucous voice… And pay attention to Ervin and Dolphy trading fours without any rhythmic section, then twos, then ones…

You can also try to catch the rhythmic variations I had evoked in the first exposition of the theme. The structure is 48 bars, A B A, and on the first A, Richmond plays a latin rhythm, and on the second he plays 3 over 4.

A beautifully tender ballad that has been recorded under different names, “Weird Nightmare”, “Pipe Dream”, “Vassarlean”… This version is intepreted in 1994 by Mal Waldron on piano and Steve Lacy on soprano saxophone.

“Smooch”, Steve Lacy/Mal Waldron, Communiqué, 1994

Mal Waldron (1925-2002) played with Mingus in the years 1954-1957 in the Cafe Bohemia recording, then with Booker Little and Dolphy. He is also known for his work as the accompanist of singers — Billie Holiday, of course, but also Abbey Lincoln or Jeanne Lee.

He did many recordings in duet with saxophonists, Archie Shepp, Steve Lacy, Marion Brown, David Murray… and all of those I’ve listened to are superb.

There’s no reason not to listen to a good song twice, so let’s go back to “Nostalgia In Times Square” — we had listened to a version by Patricia Barber on day 3.

This 1993 version by the Mingus Big Band features an exceptional trumpet chorus (Randy Brecker?), followed by as good sax (Ronnie Cuber, I’d guess), piano (Kenny Drew Jr), bass (Michael Formanek) choruses. The spoken prologue adds a kind of hip hop feeling to the natural energy of that tune.

“Nostalgia in Times Square”, Mingus Big Band 93

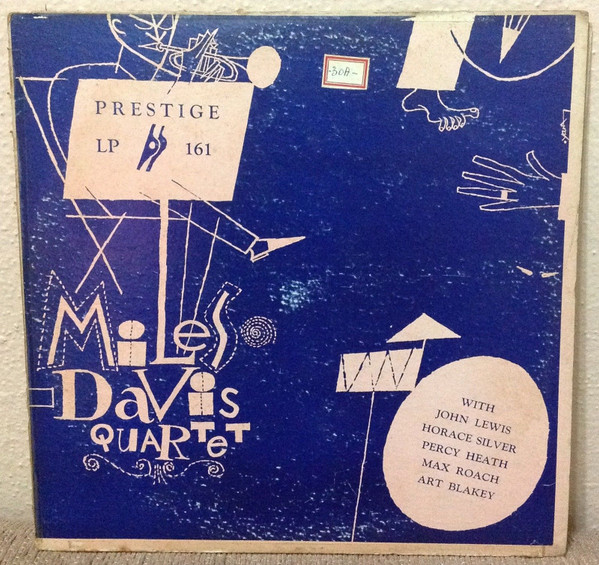

We’ve listened to that tune a few days ago, played by Mal Waldron and Steve Lacy, but upon general request, here is another version where Charlie Mingus is on piano, within the Miles Davis Quartet : Miles Davis, trumpet; Charlie Mingus, piano; Percy Heath, bass; Max Roach, drums.

“Smooch”, The Miles Davis Quartet, 1953

The 1954 album Blue Haze which features this track is a compilation of two recording sessions, in May 1953 and May 1954. For the other tracks, the pianists are Horace Silver and John Lewis. One learns on the back cover that John Lewis had to leave the session because of an emergency, and Charlie Mingus — who apparently was present, because he had composed the piece — could replace the pianist.

Maybe the apex of the bebop repertoire, a Ray Noble tune based on the harmonic progression of another one (“Indiana”), at high speed: this is “Cherokee”.

Charlie Mingus recorded it a few times, even in late concerts, but this is an early trio version, from the 1953 Massey Hall concert. Mingus is on bass, Bud Powell on piano and Max Roach on drums; A pure gem.

“Cherokee”, Charles Mingus Trio, Live At Massey Hall, 1953

All three gallop at an incredible speed, as if all horses came out from hell to pursuit them. Max Roach is on brushes, and he punctuates his fast swing (it almost sounds like a cavalcade) with bass drum “bombs”. His chorus at 3:00 is astounding of virtuosity and musicality.

I wouldn’t be so affirmative about its beginnings, but since the 30s, jazz is mostly a music of the modern city, immediately associated with New York City, although many other have seen the birth of important (r)evolutions of that music: New Orleans, Saint Louis, Chicago… Paris and Stockholm as well…

Recorded only once by Charlie Mingus in 1957, “Scenes of the City” is viewed by its composer as a musical sketchbook. “I got the idea because one of the girls I was living with was a painter. She had a B.A. in art.”

This a short (10 bar) and simple melody, mostly descending, which serves as a support for a spoken text, with variations in tempo, rhythm, mood.

This 1985 version by Branford Marsalis is shorter than Mingus’s original (5 min vs 11) and adds a bit of end-of-20th-century modernity.

“Scenes of the City”, Branford Marsalis, 1985

“I wrote it at Peggy Hitchcock’s house. We were friends. She wanted to take the blue plastic shield of the cockpit of a fighter plane and replace her skylight with it, so the sky would always be blue. The governement wouldn’t let her do it.”

I leave you to discover who Peggy Hitchcock was, and what kind of hospitality she offered to artists such as Charles Mingus, Maynard Ferguson, Allen Ginsberg. (Hint: Tim Leary is not far at all…)

So today’s tune is “Peggy’s Blue Skylight”. Interpreted in 2018 by the Mingus Big Band at Ronnie Scott’s Club (London). Wayne Escoffery is on trumpet, Helen Sung on piano, Boris Kozlov on bass, and guessing by the cap, it should be Donald Edwards on drums.

“Peggy’s Blue Skylight”, The Mingus Big Band, Live at Ronnie Scott’s Club, 2018

I’ve already evoked a few times in this thread the influence and admiration of Charles Mingus towards Charlie Parker. The present tune is kind of Mingus’s musical anthology of Parker’s music.

Mingus played it at many European concerts in 1964. I initially intended to share the version from the Norway concert which has a video, and a surprisingly long (and unprepared) introduction by Mingus, but it ends abruptly to “Take the A Train”.

So maybe the longer version at Bremen, also in 1964 is a better one. Take place comfortably on the couch, with something nice to sip, and enjoy these 21 minutes of “Parkeriana” !

“Parkeriana”, Charles Mingus, Live at Bremen, 1964

Yesterday, we listened to Mingus honoring Parker’s music, and today he plays the bass in a recording by vibraphonist Teddy Charles which honors Parker — Word From Bird.

The choice of the song is motivated by Dizzy Gillespie’s chorus in the song that I’ll offer you next Wednesday, and by some event of woman policing that happened yesterday in France.

A composition of David Raskin for a 1944 Otto Preminger movie: “Laura”.

This is a quartet version : Teddy Charles on vibraphone, Charles Mingus on bass, Hall Overton on piano and Ed Shaughnessy on drums.

“Laura”, Teddy Charles, Word of Bird, 1956

A brand new recording of a politically charged track. I don’t have lyrics for this tune that refers to the 1971 rebellion at Attica prison. But John Lennon/Yoko Onoa have some for their own song:

Free the prisoners, jail the judges Free all prisoners everywhere All they want is truth and justice All they need is love and care

![Inmates of Attica state prison in upstate New York raise their fists to show solidarity in their demands during a negotiation session with state prisons Commissioner Russell Oswald, Sept. 10, 1971. AP, [https://nypost.com/2016/08/20/the-true-story-of-the-attica-prison-riot/]](images/Attica.png)

Nelson Rockefeller was the governor of New York state at that time, and he was the one who ordered the bloody assault of the rebels, with strong support of Richard Nixon. In 1974, he would become Gerald Ford’s vice-president.

Quoted in Wikipedia, Attica Prison riot, the New York State Special Commission on Attica wrote, “With the exception of Indian massacres in the late 19th century, the State Police assault which ended the four-day prison uprising was the bloodiest one-day encounter between Americans since the Civil War.”

This 2022 version by clarinetist Harry Skoler, with Kenny Barron on piano, Christian McBride on bass, Johnathan Blake on drums, Nicholas Payton on trumpet. At the end of the Arrangement by Fabian Almazan you’ll have some recollection of the event.

“Remember Rockefeller at Attica”, Harry Skoler, Living in Sound, 2022

John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s lyrics for their song “Attica State” go on with :

They all live in suffocation Let’s not watch them die in sorrow Now’s the time for revolution Give them all a chance to grow

This is the title of a 1963 recording of Charles Mingus, devoted to a single musical piece in six movements, from “Mode A - Solo dancer” to “Mode F - Group and solo dance”.

Originally 39 min long, and arranged for 11 instruments, this version by the Mingus Big Band is shorter, 16 min, but wider since the band features some 20 people.

“Black Saint & Sinner Lady”, Mingus Big Band, Tonight at Noon, 2002

Last and least is me. Mingus. I wrote the music for dancing and listening. It is true music with much and many of my meanings. It is my living epitaph from birth til the day I first heard of Bird and Diz. Now it is me again.

This music is only one little wave of styles and waves of little ideas my mind has encompassed through living in a society that calls itself sane, as long as you’re not behind iron bars where there at least one can’t be half as crazy as in most of the ventures our leaders take upon themselves to do and think for us, even to the day we should be blown up to preserve their idea of how life should be. Crazy? They’d never get out of the observation ward at Bellevue. I did. So, listen how. Play this record.”

This is from the liner notes for the original recording, written by Mingus himself. But he also gave the pen to his then psychologist Dr. Pollock who wrote: “To me this particular composition contains Mr. Mingus’s personal and also a social message. He feels intensively. He tries to tell people he is in great pain and anguish because he loves. He cannot accept that he is alone, all by himself; he wants to love and be loved. His music is a call for acceptance, respect, love, understanding, fellowship, freedom — a plea to change the evil in man and to end hatred.”

By the way, the subtitle for Mode D is “Stop! Look! And Sing Songs of Revolutions!”.

Don’t you believe that our world is still in need that we all stop ! look ! and sing songs of revolutions ?

How do you say “seum” when you’re a black musician ? Blues, which is all I can feel now. So this week, until I’m better will be about blues, with little comments (even listening to music is painful).

From Charles Mingus’d 1960 album Blues and Roots, this is “Cryin’ Blues.”

“Cryin’ Blues”, Charles Mingus, Blues and Roots, 1960

Devil Blues, from the 1975 recording Changes 1, sung by Tenor saxophonist George Adams. If you’ve never heard a blues before, here is one.

“Devil Blues”, Charles Mingus, Changes 1, 1975

The lyrics are due to the blues musician Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown (1924-2005).

51 .Noddin’ Ya Head Blues

Yet another blues. A composition of Charles Mingus, initially recorded in 1977 for his album Three of Four Shades of Blue.

From her 2006 recording These days, Ellen Johnson sings this “Noddin’ Ya Head Blues” (lyrics seem to be hers), solely accompanied on bass by Darek Holes.

The blues has made this thread slower this week, I’m sorry. This track was first recorded in Mingus’s 1962 Oh Yeah album, but this will be a 1995 version by the Mingus Big Band.

“Hog Callin’ Blues”, The Mingus Big Band, Gunslinging Birds, 1995

The arrangement is a long chorus of John Stubblefield on tenor saxophone, with many quotes from other tunes of Mingus, and this incredible riff from Haitian fight song, recognizable among all…

John Stubblefield (1945-2005) was trained in Chicago with AACM musician Richard Muhal Abrahams. Besides his work for the Mingus Big Band for 13 years, he played with the World Saxophone Quartet, Nat Adderley, Kenny Barron or McCoy Tyner…

Published as a leader, his recordings Prelude (1977), Bushman Song (1986, with Geri Allen on piano!), Countin’ on the Blues (1987) are really good albums, but I don’t like the “disco” esthetics of his Sophisticated Funk (1990).

Just a short message for tonight, it’s election night in France, and I was wondering what tune would fit the results (good or bad, they’re certainly below what social justice and climate change demand).

Because a certain number of them will nevertheless leave politics, for good, let’s listen to this “Farewell” tune.

“Farewell, Farwell”, Charles Mingus, Something Like A Bird, 1978

While the album bears his name, it is as a composer and arranger that he contributed to the music recorded by this large ensemble on Jan 23, 1978. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis he was suffering of would take him a bit less than one year later.

While the album bears his name, it is as a composer and arranger that he contributed to the music recorded by this large ensemble on Jan 23, 1978. The amyotrophic lateral sclerosis he was suffering of would take him a bit less than one year later.

One joyful blues composed by Duke Ellington, recorded live at Carnegie Hall, January 19, 1974

“C-Jam Blues”, Mingus At Carnegie Hall, 1974

At 9:35, Roland Kirk takes a fabulous chorus. Peter Keepnews wrote in Downbeat : “Kirk a notorious scene-stealer, pulled out all the stops in his solos, to the audience’s delight. Mingus grinned like a rotund Cheshire cat through the whole thing.”

Kirk starts quietly, with a bluesy phrase, and suddenly, he starts growling, shrieking, as a parody of the preceding chorus by George Adams. Alternating between soulful melodies and continuous sound for 5 minutes, the energy will never quit him.

At 12:30, he quotes A Love Supreme ! The crowd erupts when he finishes his chorus, and I wonder how Jon Faddis dared starting a trumpet chorus after that ! In any case, the tune will end in a total musical chaos.

It’s time for some music of Charles Mingus played by somebody whose musical fame is unrelated to jazz. On electric guitar, welcome Mr Andy Summers, playing “Tonight at Noon”.

“Tonight at Noon”, Andy Summers, Peggy’s Blue Skylight, 1999

Mingus recorded that song in 1957 but it was only issued in 1964. In 1999, the former guitarist from the rock group Police devoted a whole album to Mingus’s music.

A poem by Langston Hughes put into music by Charles Mingus for a 1958 album entitled The Weary Blues.

In this 2015 version by the Mingus Big Band, the poem is recited by band member Frank Lacy.

“Consider Me”, Mingus Big Band, Ku-Umba, 2015

Langston Hughes’s musical album The Weary Blues is made of two parts, one played by Leonard Feather, the other by Mingus.

The track “Double G Train” puts into music various poems of Hughes, most of them referring to dreams, childhood, hope. It ends with the poem “Democracy”.

A 1930 song by Eubie Blake, with lyrics by Andy Razaf, recorded in August 1957 by Charles Mingus in his album East Coasting (the rest consists in Mingus’s compositions).

This may be the only recording where Charles Mingus and Bill Evans play together. It is said that Mingus called Evans at 4am to make this recording, and that he sight read the whole session.

“Memories of You”, Charles Mingus, East Coasting, 1957

Two years later, in 1959, Miles Davis would hire the pianist to record the legendary Kind of Blue. And two more years later, 1961, Bill Evans would change the sound of jazz trio with Scott La Faro and Paul Motian.

We already listened to that song on day 5, in Mingus’s 1957 version. To quote Brian Zimmerman, “he wrote [it] as an ode to the triumph of freedom in the face of persecution. The song, one of the bassist and bandleader’s most enduring compositions, features some classic Mingus tropes: an intensely brooding solo bass opening, an urgent burst of call-and-response, and, of course, a round of raucous, blues-tinged solos.”

Charles Mingus – “Haitian Fight Song”, by Brian Zimmerman

Ready for today’s version ?

Founded by a sound engineer/drummer and a trombone player, this band has 12 brass plus drums. “Trained in the conservatory and hardened in the garage”, this is the No BS! Brass Band.

“Haitian Fight Song”, No BS! Brass Band, Live recording, 2013

It’s the fourth version of that song, I think, that I propose you to listen to. Unfortunately, it might not be enough to kick those fascists out. Interpreted by the 1995 Mingus Big Band, in their album Gunslinging Bird, this is “Fables of Faubus”, in an arrangement by the alto saxophonist (and band member) Steve Sagle, who also plays a chorus. (Trumpet chorus: Philip Harper.)

“Fables of Faubus”, Mingus Big Band, Gunslinging Bird, 1995

For more info about the context of that song, a link to the day 21 of this thread.

A bit of tenderness for tonight. Recorded in 1961, published in 1964 in his album Tonight at Noon. Jimmy Knepper on trombone, Charles Mingus on piano.

“Invisible Lady”, Charles Mingus, Tonight at Noon, 1964

Peace to you all.

Tonight’s track is taken from a trio album of three leaders : Duke, Charles and Max. The album’s name is Money Jungle, a pure gem, mostly consisting of compositions of Ellington.

In this relatively unknown track, the three musicians share a relative equal part of the cake. If you’ve ever wondered how a drummer can play a melody, just open your ears.

“A Little Max (Parfait)”, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Max Roach, Money Jungle, 1962

By the way, there are two quasi-covers of this album that certainly deserve to be listened to : one is a solo recording by the pianist Aki Takase, the other is by the drummer Terri Lyne Carrington with a full hard bop band!

Let’s listen to a modern version of “Peggy’s Blue Skylight”, a song that we had listened to on day 44.

Joe Lovano assembled a large orchestra which is somewhat closer to a classical orchestra than a traditional jazz big band, with strings, harp, french or english horn. The arrangement is due to Gunther Schuller.

“Peggy’s Blue Skylight”, Joe Lovano, Rush Hour, 1995

Another version of “Invisible Lady” which we listened to 3 days ago. This version has lyrics, written and sung by Elvis Costello, accompanied by the Mingus Big Band.

“Invisible Lady”, Mingus Big Band, Tonight At Noon… Three Or Four Shades Of Love, 2002

One of the emblematic compositions of Charles Mingus, built on a few seemingly simple movements, and yet so rich.

This version is the initial one, recorded in 1956 within Mingus’s Jazz Workshop. Mal Waldron is on piano, Willie Jones on drums, Jackie McLean on alto sax, J.R. Monterose on tenor sax, and Charles Mingus on bass.

“Pithecanthropus Erectus”, Mingus’s Jazz Workshop, Pithecanthropus Erectus, 1956

An Ellington composition, by the one-shot trio of Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, from their album Money Jungle. Within a post-bop album where the musicians impose a forceful presence, this track is kind of an exception. A slow ballad; Max uses mallets, and his drumming is understated; Mingus doesn’t play a bass line, but converses with the piano.

“Fleurette Africaine”, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach, Money Jungle, 1962

This is a simple but beautiful melody whose original arrangement inspired many other ones. For more presence, you can go listen to Gary Burton, Larry Coryell, Bob Moses and Steve Swallow, in their recording “Fleurette Africaine”, Gary Burton Quartet, Lofty, 1968 or even Terri Lyne Carrington, in her project Provocative in Blue, where she revisits the full album, incorporating more modern influences: “Fleurette Africaine”, Terri Lyne Carrington, Money Jungle - Provocative in Blue, 2013. In a slightly softer direction, listen to the quartet of the pianist Laurent De Wilde. On drums, Lewis Nash stays faithful to the understated approach of Roach, but the pianist shares part of the melody with the trumpet of Eddie Henderson: “Fleurette Africaine”, Laurent De Wilde Quartet, Colors of Manhattan, 2011.

A few days ago, we listened to Mingus’s original version. Today’s one is interpreted by the quartet Dok Wallach. (Daniel Erdmann, tenor sax; Michael Thieke, saxophone/clarinet, Heinrich Köbberling, drums; Johannes Fink, bass).

Their version begins with a very free interpretation (especially on drums) with an understated melody. At some point, the theme emerges to turn into a clarinet chorus. Then a bass chorus, and the melody.

“Pithecanthropus Erectus”, Dok Wallach, Live in Lisbon, 2010

Yet another version of “Pithecanthropus Erectus”! Unfortunately, it does not seem that the Mingus Big Band recorded any version, so I’ll have to resort to another big band version. Sonando is a Seattle-based jazz band — For you tonight, they offer you an afro cuban arrangement.

Viva Mingus!

“Pithecanthropus Erectus”, Sonando, Live recording, 2012

Is there a stranger title than the one of this song?

This rarely played song has a bluesy mood. It consists of several different sections that allow for many changes in tempo, rhythm (from swing to latin), color… and of course long and imaginative choruses.

Initially recorded as a piano solo (in 1963), this version was recorded 10 years later at the Strata Gallery, in Detroit. (Bass – Charles Mingus; Drums – Roy Brooks; Piano – Don Pullen; Tenor Saxophone – John Stubblefield; Trumpet – Joe Gardner)

As noted in the Rolling Stone review, by Hank Shteamer, this is an unusual lineup, which gives this version a different sound from the classic bands assembled by Mingus.

Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus, Max Roach play this famous tune by Juan Tizol. There’s some irony since when both Mingus and Tizol were members of Elington band, a fight between them led to the firing of the bassist, a story I had already told you on day 2 of this 100-day celebration of Mingus’s music. (Already invoking irony…)

Here is this trio version of Caravan by Duke, Charles and Max, from their recording Money Jungle. (There are two parts in this theme, listen how Roach accompanies both of them, the first one on toms only, and the second on the ride cymbal and snare.)

“Caravan”, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Max Roach, Money Jungle, 1965

With its multifaceted influences, from classical music to blues to free jazz, Mingus’s music allows to be reworked. Today’s version is sung by Julie Christensen, with lyrics of her own.

Christensen and her musicians emphasize the blues aspect of that song, but you’ll hear how well it works!

“Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Dress”, Julie Christiensen, Something Familiar, 2006

On AllMusic.com, Thom Jurek writes: “One of the tremendous surprises here is her reading of Charles Mingus’‘Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blue.’ Led by Karen Hammack’s gorgeous piano playing, and the subtle, in-the-pocket bassline of Mary Ann McSweeney, she finds the bluesy swing bump right away and lets her voice swoop and swoon with just enough of an erotic acknowledgement—like the jazz singer on the bandstand who can see it all and sings to egg on the gentlemen toward the unattainable lady sitting alone at table four—o bring the imperceptible hip twitch out of the tune.”

This is a truly beautiful interpretation. Moreover, since it is quite rare, it is important to have it played and sung by women.

Yet another hearing of that song. Today’s version is a big band one (that’s the rule), but not a Mingus Big Band’s for it did not record it.

The arrangement is due to Gil Evans, and is reworked by the French pianist and band leader Laurent Cugny for his Gil Evans Workshop. Recorded at Jazz à Vienne in 2015, the soloists are Martin Guerpin on saxophone and Olivier Laisney on trumpet.

An uptempo (288 bpm) swing in homage to Bradley Cunningham, the owner of the jazz club Bradley’s, based on a famous spiritual.

The song has ben first played in 1975, but this seems to be the only recording that Mingus did, in March 1977. Two bass players are credited, Charles Mingus and Ron Carter (and George Mraz for other tracks), but I can’t tell if the two of them play.

“Nobody Knows (The Bradley I know)”, Charles Mingus, Three Or Four Shade Of Blues, 1977

There are 5 choruses: Sonny Fortune (alto saxophone), John Scofield (electric guitar), Jack Walrath (trumpet), Philip Catherine (electric guitar), and Ricky Ford (tenor saxophone). Bob Neloms is on piano and, as often, Dannie Richmond is on drums.

By a trio consisting of Charles Mingus on bass, Hampton Hawes on piano and Danny Richmond on drums

As you’ll hear, it’s very distant from classic Gershwin interpretation, where the heat of the summer prevents us from even talking.

It starts like an African dance, it goes on with an American dance, continues with a drum solo, a bass solo made of a repeated rhythmic pattern, then with a syncopated version of the theme, before the dancers progressively move away…

“Summertime”, Charles Mingus, Hampton Hawes, Dannie Richmond, 1957

“I am three” is a German trio, consisting of Silke Eberhard on saxophone, Christian Marien on drums and Nikolaus Neuser in trumpet. In 2016, they recorded a Mingus album with the explicit title : Mingus, Mingus, Mingus.

Faithful to the spirit of Mingus’s music, even to its sound, but with deliberately freeer influences, in particular from the drums which hold a triple role: rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic—it substitutes the bass! (The whole album is remarkable!)

“Opus Four”, I am three, Mingus, Mingus, Mingus, 2016

I don’t know why Mingus chose this title for a 1972 rearrangement of the tune he had composed in 1965, already with a long title : “Once Upon a Time, There Was a Holding Corporation Called Old America”.

Whatever you understand of this title, remember Mingus’s words: — “The title is signifying. I was always signifying.”

This version by the “Big Band Charlie Mingus” was recorded in June 1988 at the Théâtre de Boulogne-Billancourt, near Paris. (Listen how the band plays the melody below some choruses…)

This band mixed prominent members of Mingus’s bands (Jaki Byard, John Handy, Clifford Jordan) and young cats (Randy Brecker, Billy Hart, David Murray…). Reggie Workman is on bass. A few years later, in 1991, Sue Mingus, Mingus’s window, would form the Mingus Big Band, with those cats and many other jazz lions…

Two days ago, we were listening to “The Shoes of the Fisherman’s Wife Are Some Jive Ass Slippers”, and I had written that it was a rearrangement of a 1965 song: “Once Upon a Time, There Was a Holding Corporation Called Old America”.

So it is appropriate to listen to this earlier song, isn’t it? If you listen to a few bars of the former one, you will immediately notice the shift of keys, but otherwise, they’re pretty similar.

On AllMusic.com, Jeff Tamarkin has some story about this 1965 concert, done one week after a Monterey concert in which Mingus hadn’t been able to play all the music that he had composed for an octet (himself on bass and piano, Charles McPherson on sax, Dannie Richmond on drums, Julius Watkins on French Horn, Hobart Dotson, Lonnie Hillyer and Jimmy Owens on Trumpet, and Howard Johnson on Tuba).

This was work in progress, that Mingus himself labelled as Jazz Workshop, and the full recording includes a lot of false starts that led Mingus to reduce his band to a quartet for some tunes. However, the full octet is back for that version.

A 1960 recording by Charles Mingus and the Jazz Workshop.

Most of the track is a duet between Dolphy and Mingus. At some points, Ted Curson adds a beautiful second voice to Dolphy’s free interpretation.

“Stormy weather”, Eric Dolphy and Charles Mingus, Mingus, 1960

A few years before, Mingus had recorded another version of “Stormy Weather”, with bass, drums, cello, clarinet, saxophone and trumpet. It is beautiful as well, we might listen it in a few days ;-)

That should be our fourth version of that tune in this thread devoted to Mingus’s music, on the occasion of the 100th birthday of this immense musician, composer, band leader…

Today, we listen to a 2002 version by Jessica Williams (1948-2022). She was a masterful jazz pianist and composer. As the house pianist of the San Francisco Keystone Corner Jazz Club, she played with many of the greats, Philly Joe Jones, Tony Williams, Stan Getz…

Here is her version of this tune of Charles Mingus.

“Orange Was the Color of Her Dress Then Blue Silk”, Jessica Williams, All Alone, 2002

Well, she obviously was a great… Dave Brubeck even called her “one of the greatest jazz pianists [he had] ever heard.”

This is taken from a solo album that Jessica Williams recorded in 2002 where she plays standards, more modern tunes, and compositions of her.

If you wish to discover her work, NPR made several interviews of Jessica Williams: Remembering jazz pianist and composer Jessica Williams, by Terry Gross or Jessica Williams on Piano Jazz, with pianist and NPR host Marion McPartland.

One of the titles that Mingus would collect in his monumental “Epitaph”, here is a version by the Mingus Big Band, recorded in 1995.

Please Don’t Come Back From The Moon, Mingus Big Band, Gunslinging Birds, 1995

When France is hit by a disastrous heat wave, special dedication to all of those who believe that technology will save us from the nightmares of necroliberalism, this 1962 tune of Charles Mingus.

In his biographical book on Mingus, Krin Gabbard views such titles as an act of poetry. But remember also what Mingus told Nat Hentoff (about “Remember Rockefeller at Attica”): “I ought to give titles to my music that make people think.”

These informations come from the following two books on Mingus and his music:

– Better Git it In Your Soul - An Interpretative Biography of Charles Mingus, by Krin Gabbard

– Myself When I am Real. The life and music of Charles Mingus, by Gene Santoro

This file stems out a series of Twitter threads, that was unthreaded day after day from April, 22, 2022 on. You can also get it on Markdown or PDF formats.

There is also a YouTube playlist that collects all of these recordings.