February-March 2022

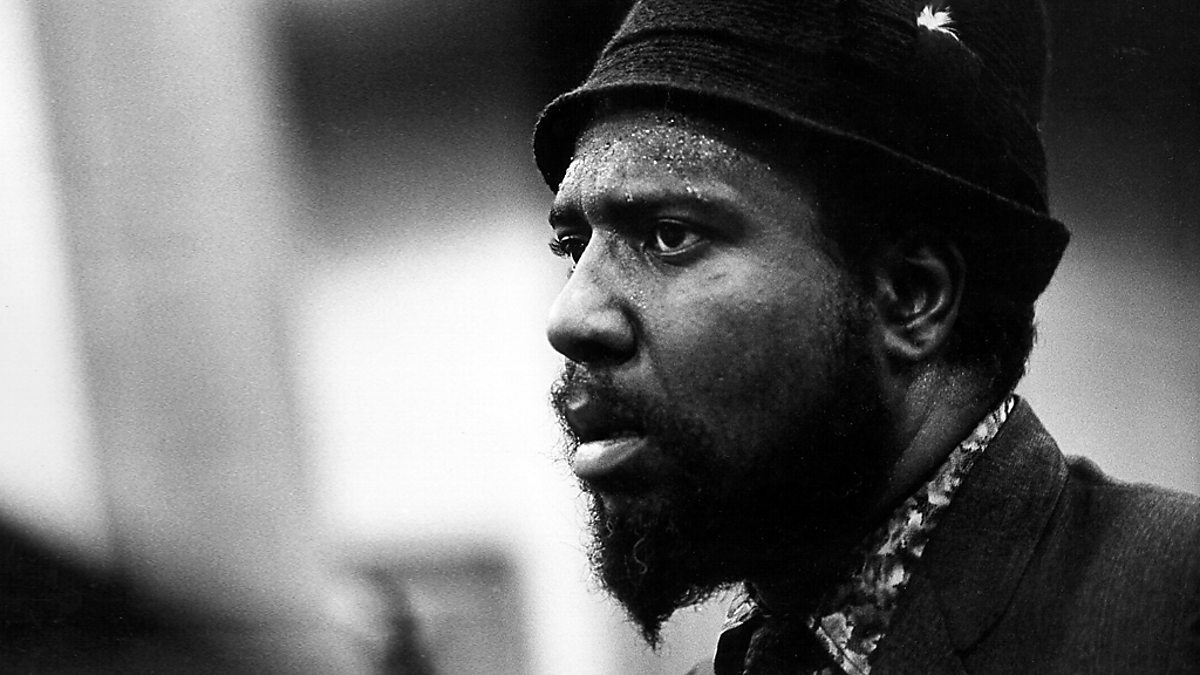

The pianist and composer Thelonious Monk died on February 17th, 1982 – 40 years ago. During the next 40 days, I propose you to listen to 40 compositions of this great jazz master, either by/with him or more recent interpretations.

The first theme I propose you to listen to is Blue Monk. Thelonious Monk is on piano, with Charlie Rouse on saxophone, Ben Riley on drums, Larry Gales on bass. Recorded in Norway, 1966.

Thelonious Monk quartet, Blue Monk, 1966

On this second day, it will be Round midnight, performed by Miles Davis’s quintet, Miles Davis on trumpet, Herbie Hancock on piano, Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Ron Carter on bass, Tony Williams on drums. It was recorded in Sweden, 1967. Like many of Monk’s tunes, the original version was a kind of twisted dance, but Davis’s interpretation turned this theme into an unforgettable ballad.

Miles Davis quintet, 1967, Round midnight

From the “Underground” recording (1967). Same nice quartet as two days ago: Monk (p), Charlie Rouse (ts), Larry Gales (b) and Ben Riley (d).

Thelonious Monk quartet, 1967, Boo Boo’s Birthday

Family was important for Thelonious, his wife Nellie (we’ll hear about her later), who supported him all his life, and his children Thelonious Jr <@tsmonkofficial> (who became a drummer) and Barbara — Boo Boo. Barbara was also the name of T’s mother.

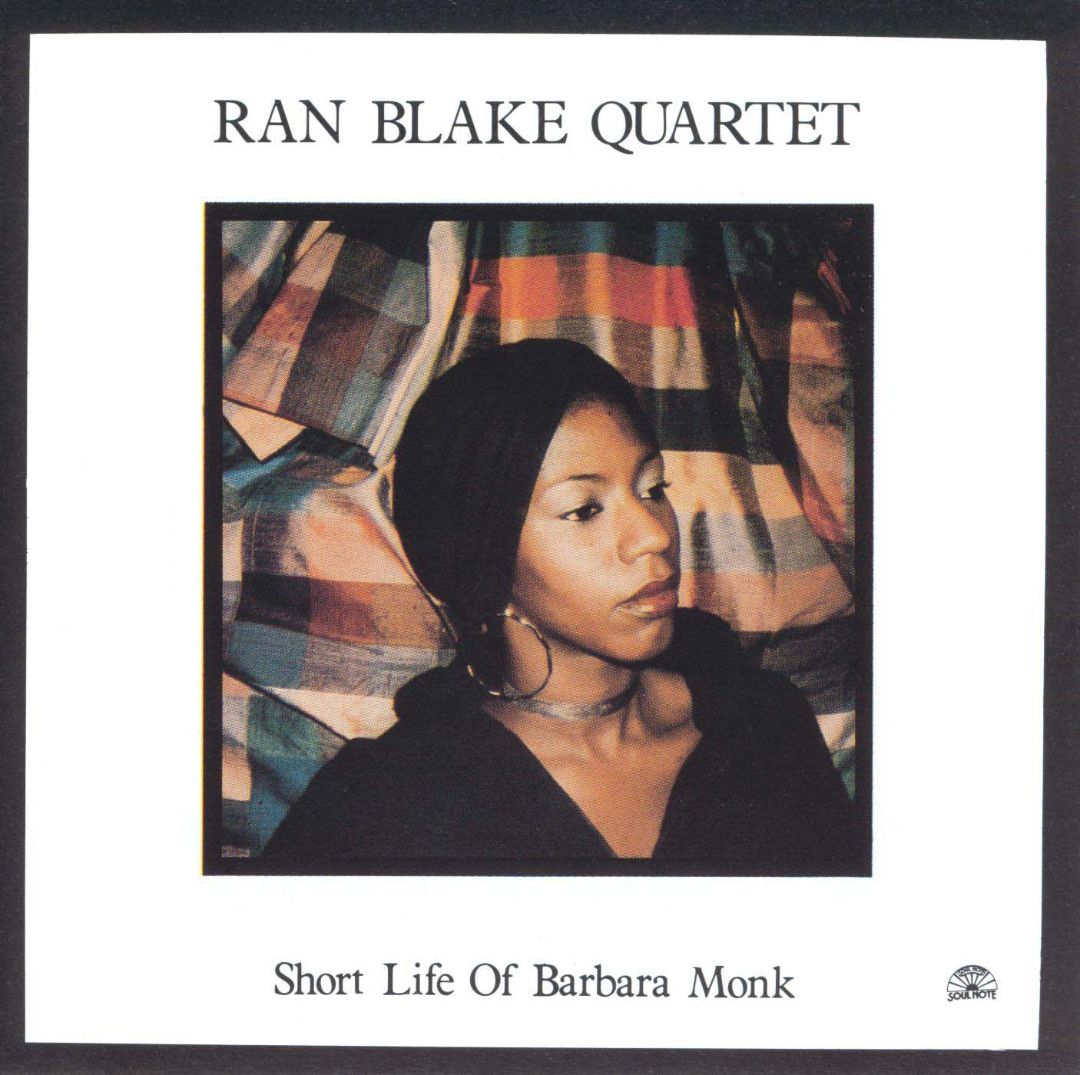

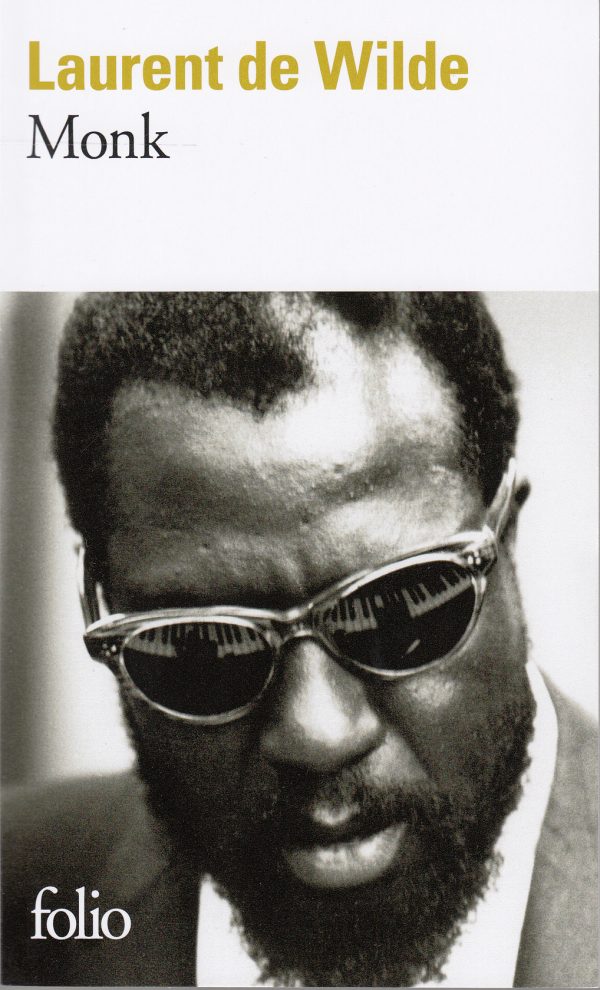

Boo Boo was also a pianist and composer — she died too young (1984, at 31). In his biography of the pianist, Laurent De Wilde says her compositions show a real talent, with a deep personality. Pictured, a recording that the pianist Ran Blake did in her honor.

Since this is a family birthday-day at home, I thought this relatively unknown song would be a nice fit. Whatever it is at your place, celebrate!

Today, I invite you to listen to Dianne Reeves’s interpretation of a beautiful song composed by Thelonious Monk, with lyrics by Jon Hendricks: Reflections.

She’s alone, with Peter Martin on the piano.

This melody had been first recorded in trio by Thelonious Monk in 1952, with Max Roach on drums and Gary Mbapp on bass, first issued in 1956, at a medium tempo. Thelonious recorded it alone in Paris, 1954, and André Francis gave it the title “Portrait of a heremit”.

In any case, you’ll certainly observe, as in the case of Round midnight 2 days ago, how Monk’s music can be interpreted in much softer ways than what Monk himself proposed in his first recordings.

On his website, Matthieu Marthouret <@Matt_Marthouret> suggests other beautiful interpretations. Of course, Motian’s trio — drums, guitar, saxophone, proposed a wonderful version, and we’ll have to listen to them more than once.

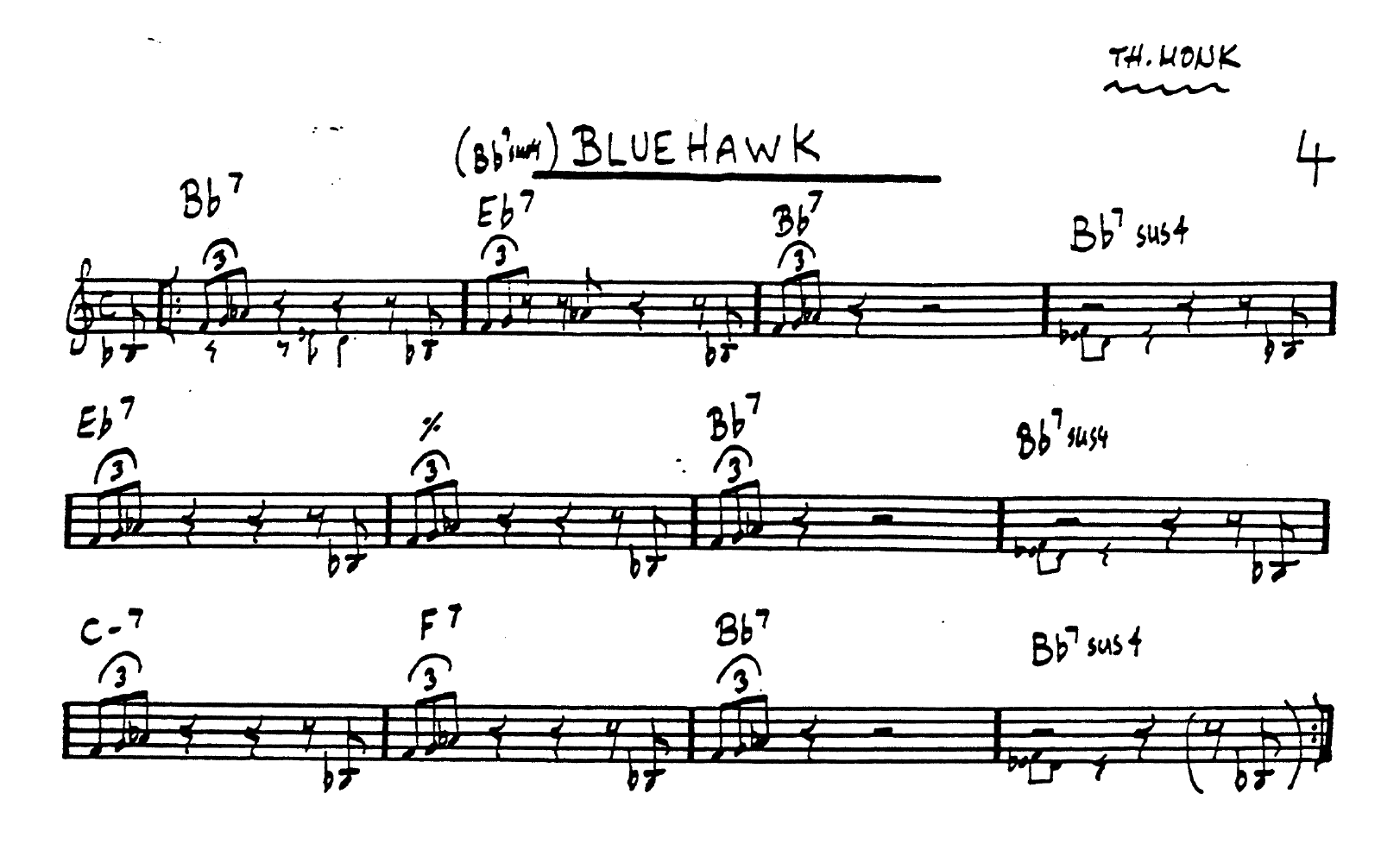

This is a blues made out of 4 syncopated notes: Bb F G Ab, starting just before the 1st beat, and ending before the 2nd one.

While Monk had played regularly with all the founders of bebop since 1941, he sounded differently from them. In 1944, the saxophone player Coleman Hawkins was the first one to hire Monk as his regular pianist, and it seems this song refers to him.

It does not seem to have been recorded very often, apparently even just once — for the famous 1959 Alone in San Francisco recording.

Thelonious Monk, Blue Hawk, Alone in San Francisco, 1959

Interpreted by Paul Motian’s electric bebop band : Steve Swallow on electric bass, Kurt Rosenwinkel and Brad Schoeppach on electric guitars, Chris Potter and Chris Cheek on tenor saxophones, and Paul Motian on drums.

Paul Motian and the electric bebop band, Pannonica, Flight of the Blue Jay, 1997

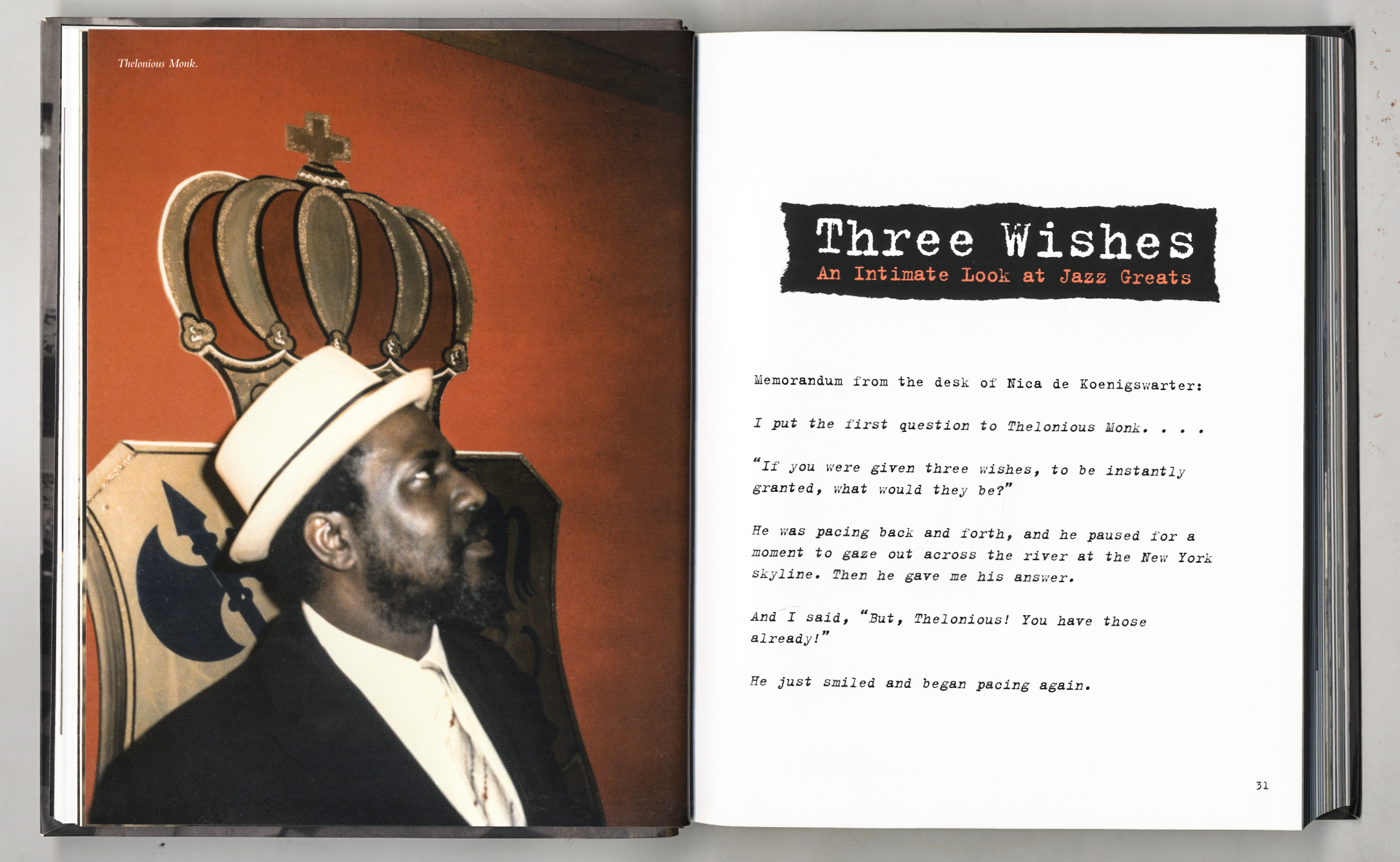

Born 1913 in London, Pannonica de Koenigswarter was a prominent figure in the life of Thelonious Monk and of many jazzmen, such as Charlie Parker who died in her hotel room.

n 1951, Monk was arrested on drug charges and his cabaret card was taken away for 6 years, in which he wasn’t allowed anymore to play in clubs. (Then his wife, Nellie provided.) It is Pannonica who paid for the lawyer that ultimately would have him recover his card in 1957.

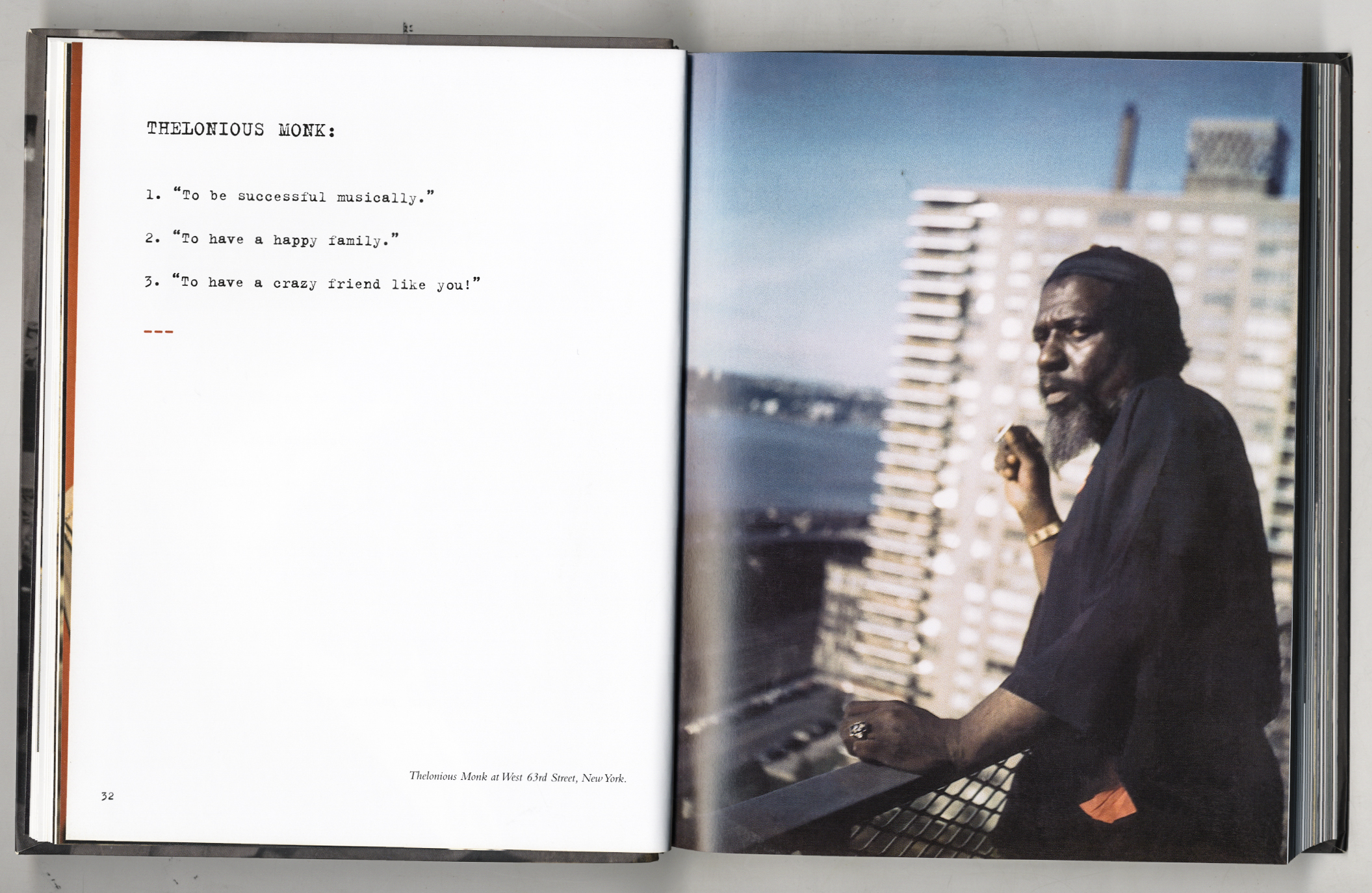

From all jazz musicians she supported, Nica collected their “three wishes” — Here are Thelonious’s:

To be successful musically

To have a happy family

To have a crazy friend like you

The last 10 years of his life, Monk recluded in almost silence with his wife at Pannonica’s place, in Newhawken, New Jersey, where he died, 1982.

Most of Thelonious Monk’s recordings involve small formations (trio, quartet…), but in 1959, the musician Hall Overton set up big band arrangements of Monk’s music.

Thelonious Monk Orchestra, Thelonious Monk, 1959

As often, Monk starts a piece by a 4/8 bar statement which is strongly reminiscent of the first phrase of the theme, if not the very first phrase. The arrangement of the song Thelonious shows very clearly how Overton dispatches notes among the brass section.

The whole recording is a gem. I hope you will find the time to enjoy it in full, for his reinterpretation of Monk’s music is absolutely beautiful. By the way, Hall Overton was born yesterday, 1920, and died 50 years ago (from liver cirrhosis).

Four years later, Hall Overton would set up a second big band concert, this times at the Lincoln Center, Philharmonic Hall, New York. Another extraordinary recording that we’ll have to listen to during these 40 days of celebration of Thelonious Monk.

When Monk plays his own music, it always has an unmistakable taste of awkwardness, sometimes it sounds out of tune, out of time (although he has a perfect sense of time), out of nowhere… Like his dreams maybe.

However, his music can be reinterpreted in all styles, sometimes in a very lyrical and soft way, and sometimes bands convey a bit of the twisted dance pieces that Monk wrote for us.

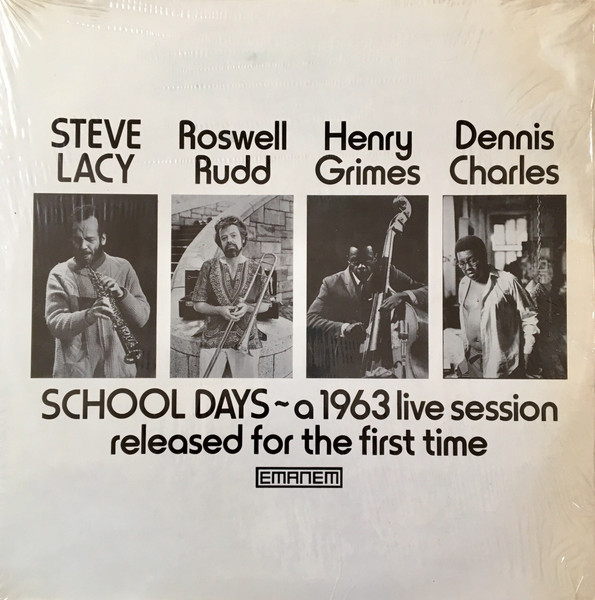

Although it has no piano, it seems to me that today’s band is faithful to Monk’s style. Roswell Rudd is on trombone, Steve Lacy on soprano saxophone, Henry Grimes on bass and Denis Charles on drums. This is Monk’s Dream !

[Steve Lacy—Roswell Rudd Quartet, Monk’s Dream, School days, 1963]

This recording has been made during a 1963 live performance at the Phase Two Coffee House in New York City.

Excellent trading in fours by Dennis Charles and his companions at the end of the solo parts, go listen how this prominent free-jazz drummer still plays with the codes of bebop, bringing sentences of 3 beats that spread over the 4 bars…

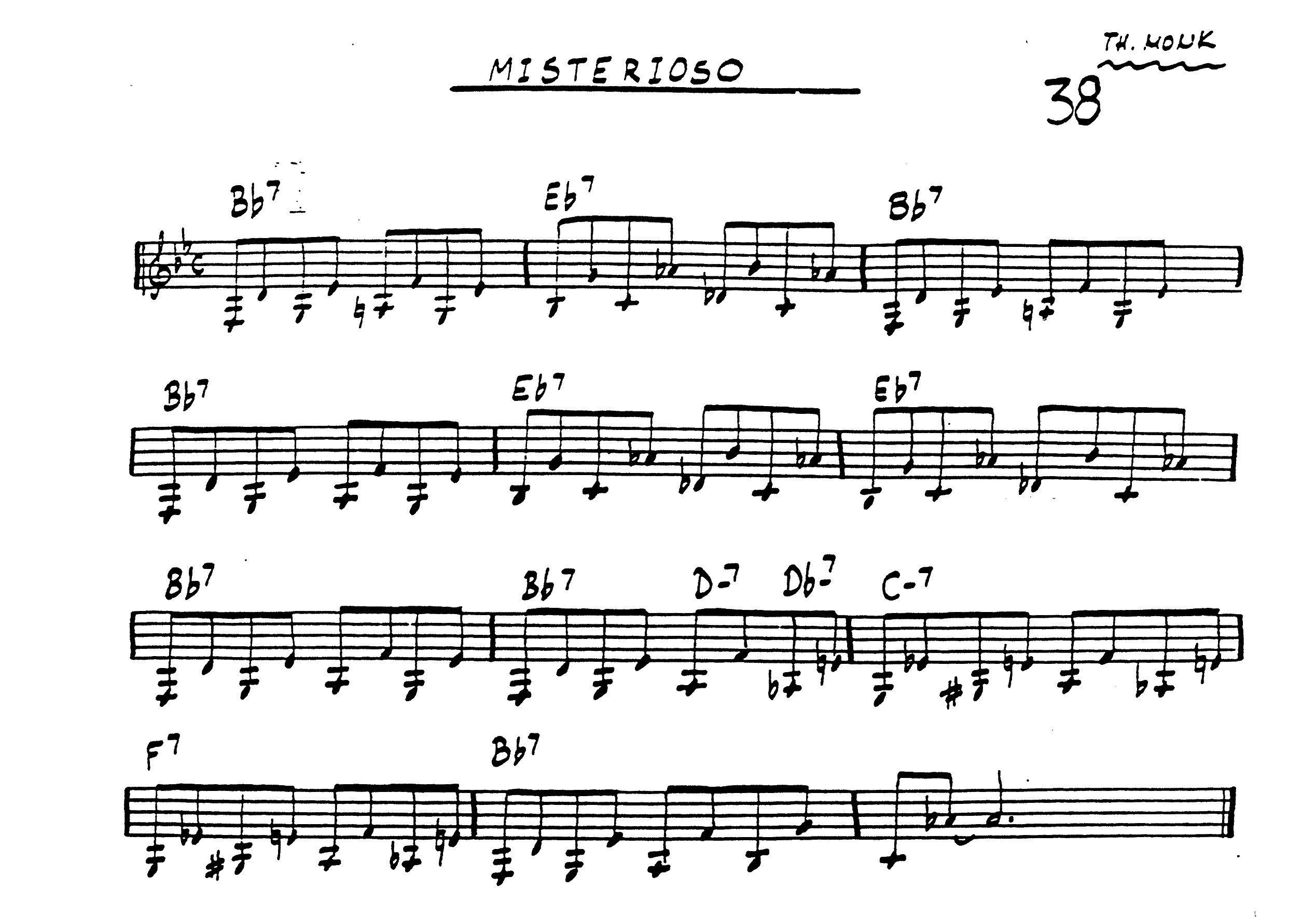

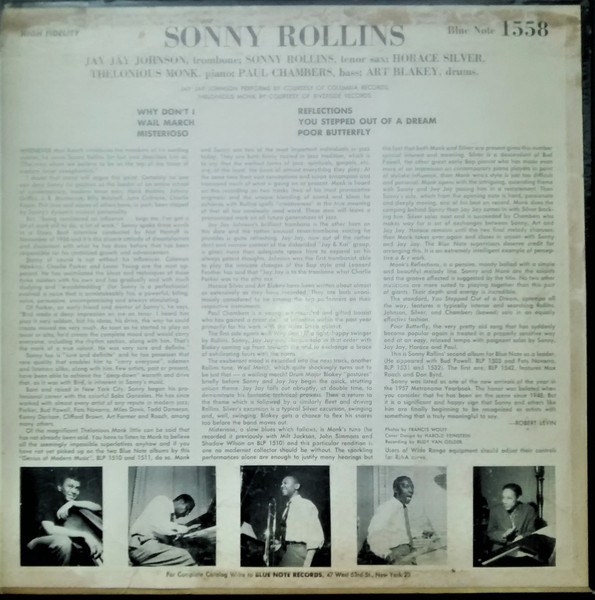

Today, we’ll listen to Misterioso. A 1957 recording under the name of Sonny Rollins (tenor sax), with Thelonious Monk on piano, Art Blakey on drums, Jay Jay Johnson on trombone and Paul Chambers on bass.

Sonny Rollins, Misterioso, 1957

Take Monk outside of this line-up, and you have a wonderful pure hard bop band, Art Blakey starts with a thick fat drum roll that launches the music, and plays all sort of drum calls, Johnson’s trombone is deep and swinging, and Chambers’s bass sings marvelous lines.

Of course, there’s Sonny Rollins on saxophone. At the age of 27, that’s his 5th recording, the second one with Monk who,at 40, is definitely older. Here, a picture of the two guys.

But, remember, this is a Monk’s theme. Misterioso. Mysterious. A blues whose melody is written like it only plays the chords as for the left hand of a Mozart piano sonata. And this is not the only trace of bizarrerie that this piece exhibits.

On the first exposition of the theme, there’s only Monk’s piano and Blakey’s swing on a riveted ride cymbal, but pay attention to the rim shots on the snare — he plays uneven triplets. On the second one, the saxophone comes in, and the triplet feel is stronger, as if Blakey wants this tune to be sound like a fast waltz. But this is the time of Rollins’s chorus, and it seems we’re safe into hard bop again. Are we? Listen to the way Monk sets the chords on the piano. Is it a piano or is it a car honk?

Around 3:00, a small piano chorus starts, and Monk unfolds his own version of the theme. Back into hard bop with Johnson’s chorus, it seems the piano will pleay reasonably — apparently, this is when Blakey wants to add some twists to his play, only for a few bars.

5:00 Piano chorus again, with Blakey hard hitting simple quarter notes, a few triplets to launch the second turn, and switches to a simple swing. Sextuplets on rim-shots to launch the bass chorus. OMG, this is so perfectly done!

After that, a trading-in-fours sections, shared between saxophone, trombone and drums. What do you think of Rollins playing this completely incongruous Camptown Races (in French, le port de Tacoma) at the end?

It’s time to go back to playing the theme. Once on the piano (with Blakey playing triplets), once again with the saxophone, piano and sax playing each other note. And we’re done! I hope you enyoyed this theme and even had some laugh at the final piano note!

A simple swinging ballad, like a simple walk in a forest or along the seashore. At least that’s what I feel from this amazingly “simple” interpretation by the Peter Bernstein Trio.

Peter Bernstein Trio, Let’s Cool One, 2008

The whole 2008 recording is titled Monk and consists in 12 renditions of Monk’s music, and we’ll listen to the first track. Peter Berstein is on guitar, Doug Weiss on bass and Bill Stewart on drums.

The theme is 16-bar, AABA form, in Eb. The A part is mainly organized in quarter notes, the B has more syncopation. But if you look at the score and compare the notes with the indicated chords, you’ll probably notice some fun stuff — that the melody does not play on the ground notes of the chord, but on the 6th or 7th! Even when he writes something seemingly simple, Thelonious Monk cannot help adding his twist.

When he states the theme, Peter Bernstein plays the melody with a welcome simplicity — this is a cool one. Bill Stewart, playing brushes on the drums, adds some punctuation at the hi-hat and Doug Weiss’s bass is quiet and solid. The musicians put in more energy in the chorus section. Stewart takes his sticks and the walking bass is more present. After two choruses on the guitar, Doug Weiss plays a beautiful one on the bass, then Bernstein and Stewart trade fours—listen how the drummer plays in colors.

Oh sure I needed to have you listen to this now standard tune by Monk, with his incredible septet, himself on piano, Wilbur Ware on bass, Art Blakey on drums, three saxophones and a trumpet — Gigy Gryce on alto saxophone, Coleman Hawkins and John Coltrane on tenor saxophone, and Ray Copeland on trumpet. You will listen how the two tenors join their forces making Monk’s music a kind of bridge between original bebop and more modern jazz.

Thelonious Monk septet, Well You Needn’t, Monk’s music, 1957

Interestingly enough, the cover picture of this 1957 recording mentions Hawkins, Blakey and Gryce, but not the other three. You’ll probably appreciate the irony of picturing Monk sitting in a child cart…

The tune featus a 32-bar AABA form. The A is built from a repeated syncopated 2-bar motive, with a slight modulation on the second repetition (playing different notes of the same Gb7 chord). The bridge is also made of a repeated syncopated pattern of four eigth notes, 4 bars of a kind, and a 4-bar chromatic progression from Eb7 to C7, 2 chords per bar, until the final C brings us back on the melody (starting with A#-A-C-F-C).

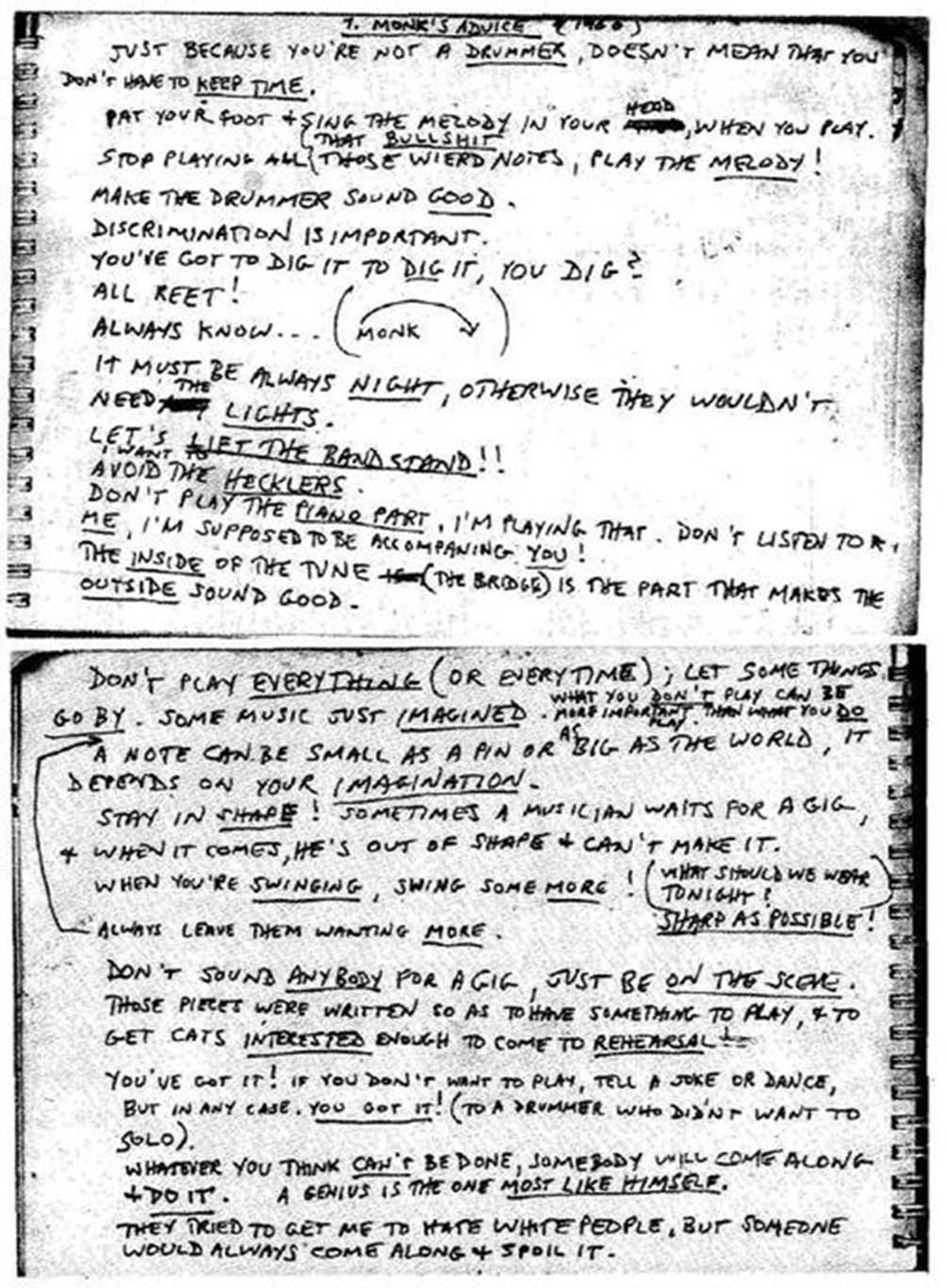

Did I tell you about Monk’s recommendation about a bridge, the inner part of a tune (as transcribed by saxophonist Steve Lacy)

THE INSIDE OF THE TUNE (THE BRIDGE) IS THE PART THAT MAKES THE OUTSIDE SOUND GOOD.

(Yes, Lacy wrote that in block letters!)

After some introductory notes, the theme is exposed by the brass sections, and Monk only plays some bizarre notes on the only space that the melody left available. Then a piano chorus, sounding a bit distant, only accompanied by bass and drums. And, at 2:20, he orders — Coltrane! And we’re off for two very coltranesque choruses on tenor saxophone, with Monk playing fun stuff to accompany him. Then two choruses on the trumpet, in a more classical style, and without accompaniment. One bass chorus. Two drums choruses, Blakey is so good! And two for Hawkins as well, but listen how he sound differently from Coltrane. Then Gigy Gryce takes his two, there’s more space I feel. Monk takes another chorus that is more like a close variation around the melody, with more intensity from the bridge on. And everybody sings the melody once more, two As ending with a piano call, the bridge, with musical sheets on brass, and the final A, and a few final notes which tell us that this is over, but that we can take our time to leave if we wish.

Thelonious Monk’s music, how awkward it may sound, is often joyful, like a pun you’re not sure you understand, but find funny anyway. And today we will be facing such a thing . Ladies and gentlemen,

Evidence

Paul Motian Trio, Justice (Evidence), Monk in MOTIAN

From a 1988 version by a wonderful trio, Paul Motian on drums, Bill Frisell on electric guitar, Joe Lovano on tenor saxophone.

No piano, no bass section. Three marvelous improvisers confronting the music directly. The title of the recording is Monk in MOTIAN. With a pun. Only Monk tunes, as Monk is a composer-of-choice for this trio, as for many bands that the drummer Paul Motian set up. I also find some Monkesque spirit in some compositions of Motian, such as his Mumbo Jumbo, go listen to that if you’re curious!

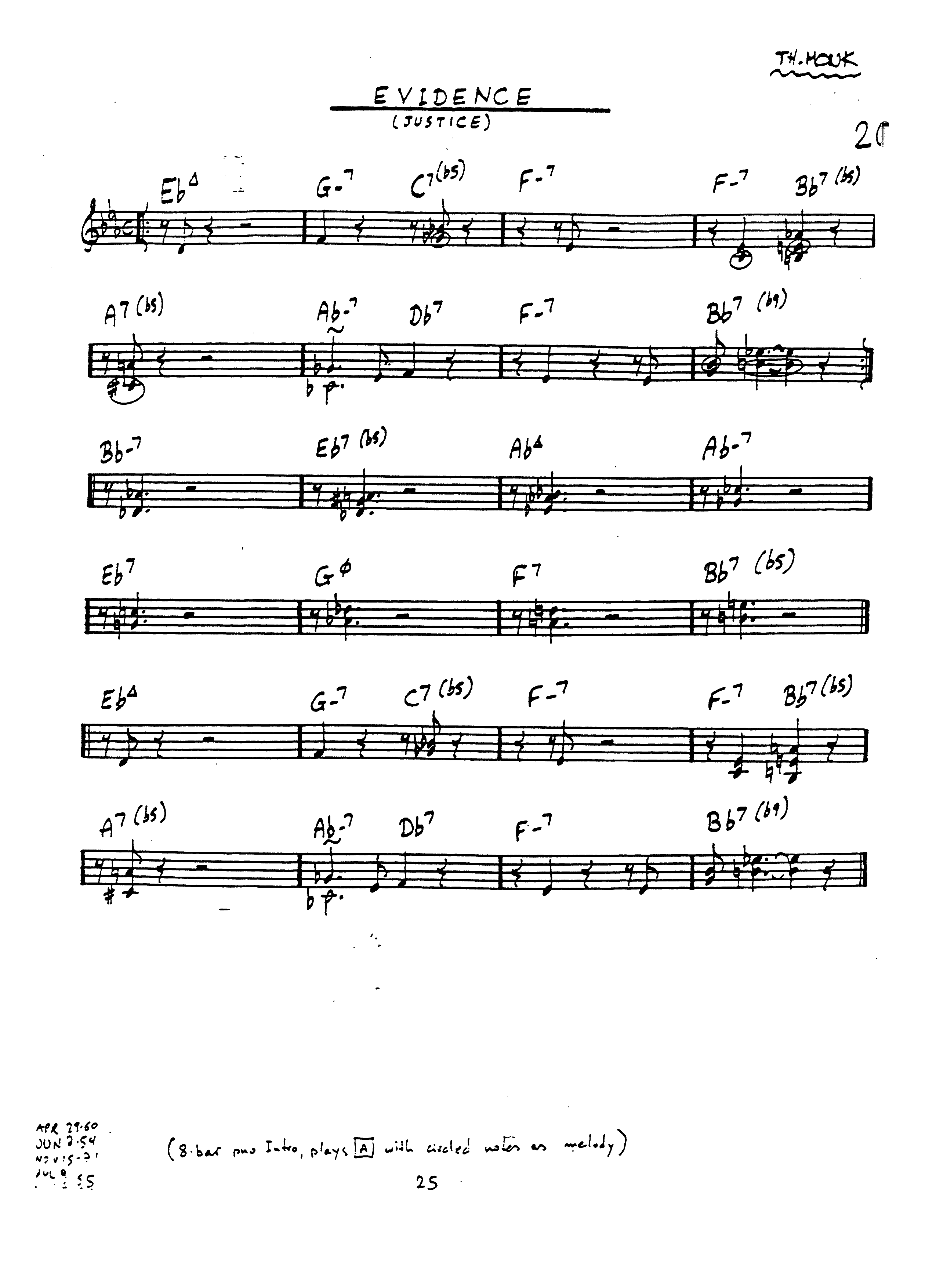

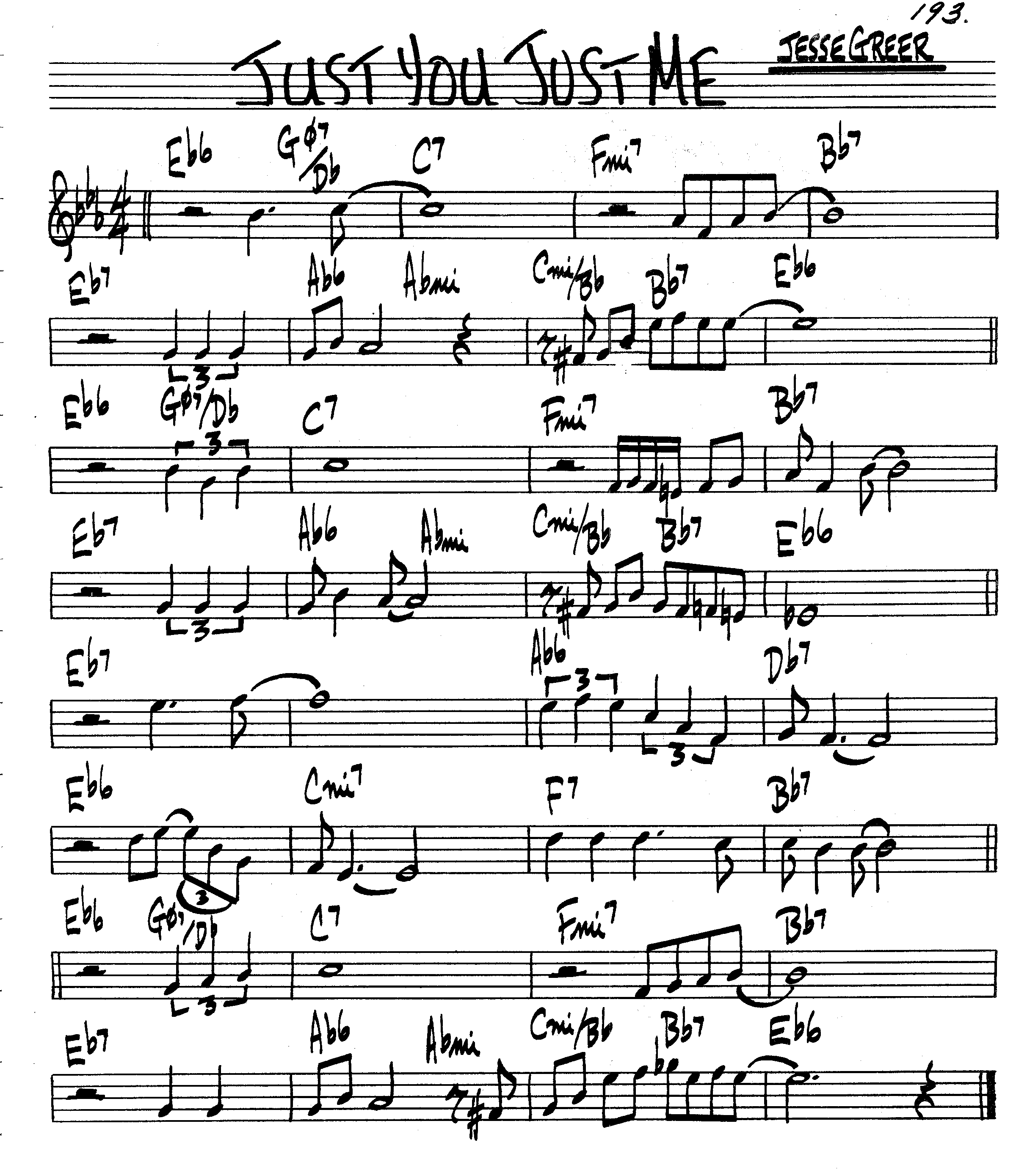

But today is Evidence. This is a 32-bar theme, AABA form, which is built on the same harmonic progressions than a 1929 standard, Just You Just Me. As you can see, it’s pretty similar. Using the chord changes from a theme to make another one was pretty standard in the bebop era, this is for example how Charlie Parker turned the classic Indiana into the furious Cherokee.

There are many interpretations of Just You Just Me, if you wish, go listen to Monk’s own — Thelonious Monk Trio, Just You, Just Me.

So, back to the pun. Remember the title of today’s theme? Just You Just Me — Just Us — Justice — Evidence.

That’ll be all for today, I leave you with Monk’s music — the urge for justice. The comments in the video above, uploaded by the Jazz Guitar Comprehesice website suggests some other versions, especially one Monk recording by the Wynton Marsalis Standard Time project, which combines the feeling of extremly well prepared arrangements with a deep sense for modern music.

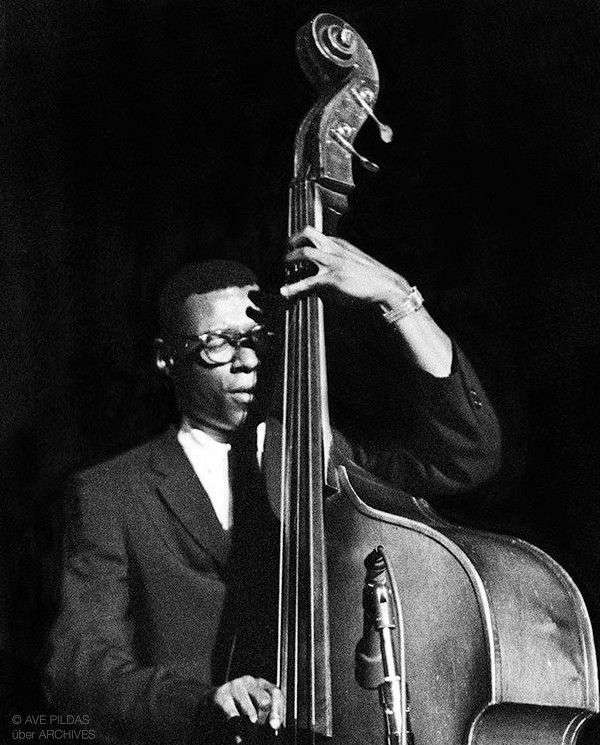

Ahmed Abdul-Malik is on bass, Johnny Griffin on tenor saxophone, Roy Haynes on drums, and Thelonious Monk is on piano. Recorded at the Five Spot Café, New York City.

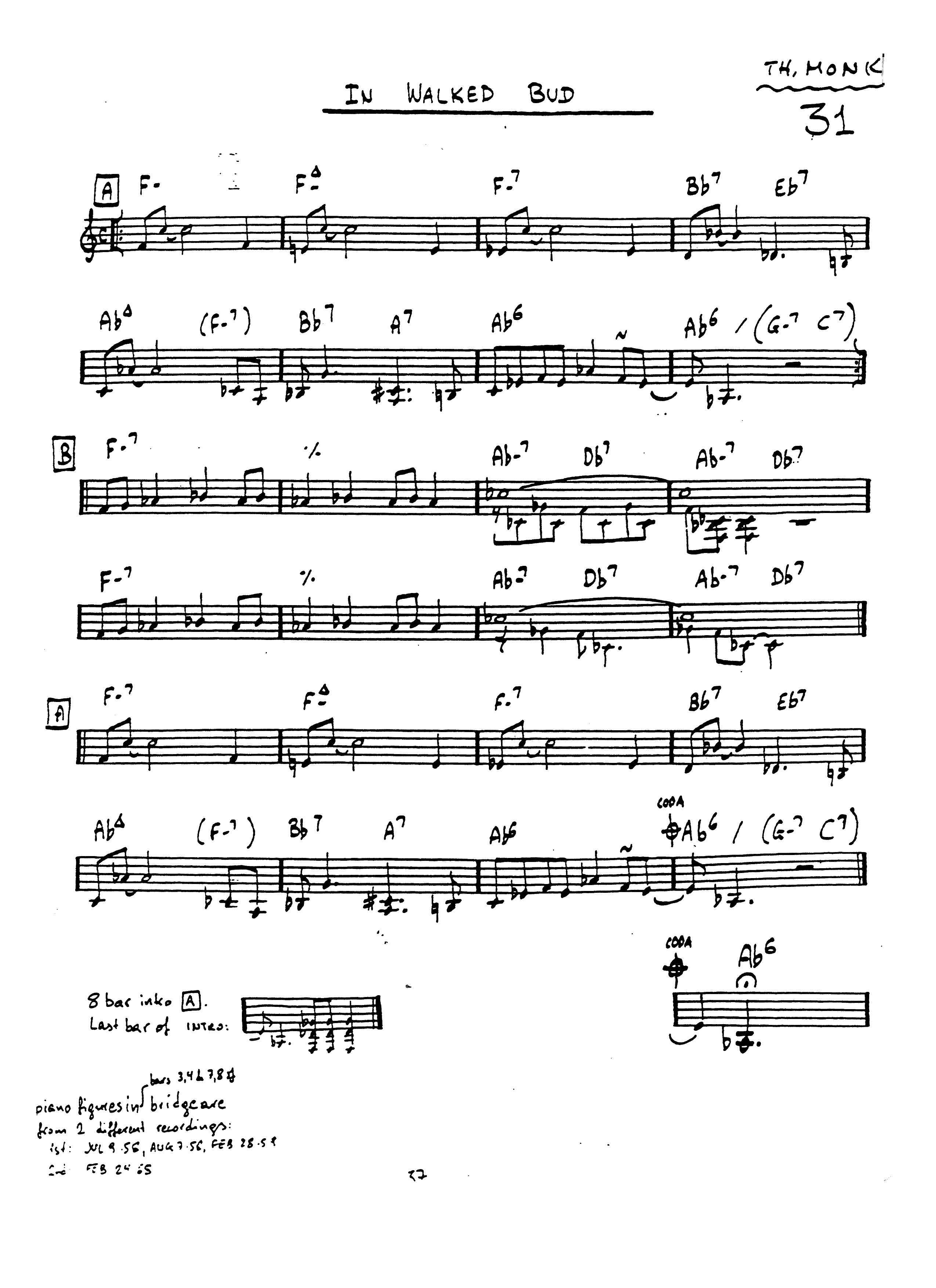

Thelonious Monk Quartet, In Walked Bud, 1958

32 bars, AABA form, with syncopated phrases that spring their step on the beat rather than on the previous 8th note, so that the relevant note (these C on measures 1 2 3) floats in the air.

The structure of the interpretation is classic for all Monk tunes. Monk alone states the first 8 bars as an intro, and then the melody starts again with piano and sax. Listen how the sax plays these C notes.

Johnny Griffin plays 9 choruses; Monk is quite present on the As of the first 3 ones, but always leaves more space on the B. From chorus 4 on, the sax is alone with the rhythm section, and gradually Haynes uses the space left by Monk to put more accents on the drums. At each turn, one hears Monk shouting at him, requiring for one more chorus. During the second part of Griffin’s choruses, it seems that the speed increases, from 170 to 200 beats per minute… So much energy!

Then come Monk’s choruses. It seems that he starts by forgetting to play one of the As, or maybe I couldn’t keep track of the beats during the transition between Griffin’s and Monk’s choruses. Anyway, it seems I’m the only one that this disturbs. Around 7:30, you’ll listen to somebody snapping fingers in rhythm, either Griffin or Monk himself to keep everybody’s rhythm in track.

Abdul-Malik takes two choruses on the bass, the first one has a straight rhythm, almost only quarter notes, and the second one is rhythmically more involved. And then comes Haynes’s solo. t is remarkable how the first chorus makes the melody so apparent — you can follow the tunes from what Haynes plays on the drums, not only the distinction between the A and B parts. Melodic drumming at its best. In the second chorus, Haynes puts in more chops.

It’s time for a final telling of the theme, and we’re gone with this hearing of In Walked Bud by Thelonious Monk’s 1958 quartet.

But who’s that Bud ?

Of course, it’s Bud Powell, one of the prominent pianists of the bebop era and a good friend of Monk. There are slightly contradictory versions of why Monk dedicated this tune to him but most of them converge to a 1945 police raid at the Savoy ballroom in which Monk and Powell have been arrested in force. “Stop, you don’t know what you’re doing. You’re mistreating the greatest pianist in the world.” Powell had said to the police before being fiercely beated. Brutalities that are said to have led to Powell’s institutionalization and future health issues.

This is the only waltz that Thelonious Monk ever composed, in 1967 or, to be safe, the only that we have a trace of. According to pianist Ethan Iverson, it was Ben Riley’s idea to have it played as a waltz, see Thelonious Sphere Monk Centennial, Primary and secondary document

In 2017, Denny Zeitlin gave a solo concert around Monk’s music, including this very tender version of that tune.

It’s hard to tell what could make this tune ugly, actually, especially when it is played so beautifully like Denny Zetilin does…

… unless you’re versed into chords reading (which I’m not) and you watch out this DØ chord that opens the theme : D-F-Ab-C. Two minor 3rd, and a major 7th.

If you rewind the above video and listen to what Zeitlin says during the first minute, the one that I had you skip, you’ll have the same explanation — “Monk heard an”ugly beauty" in the interval of a major seventh (minor second), and it colors his only waltz.”

“It was a new song.” said W.E. Dubois in 1935 about black music, quoted by Adam Shatz in his review, Blues To Come of a Harriet Tubman recording. Let’s read the quotation further:

“And its deep and plaintive beauty, its great cadences and wild appeal wailed, throbbed, and thundered on the world’s ears with a message seldom voiced by man… They sneered at it—those white Southerners who heard it and never understood. They raped and defiled it—those white Northerners who listened without ears. Yet it lived and grew… and it sits today at the right hand of God, as America’s one real gift to beauty; as slavery’s one redemption, distilled from the dross of its dung.”

There are many other interpretations, some of them even have lyrics, written by Mark Ferro, which were beautifully sung by Carmen McRae.

“Dim the lights and let’s go on pretending that this time its real … and still we dream of love.”

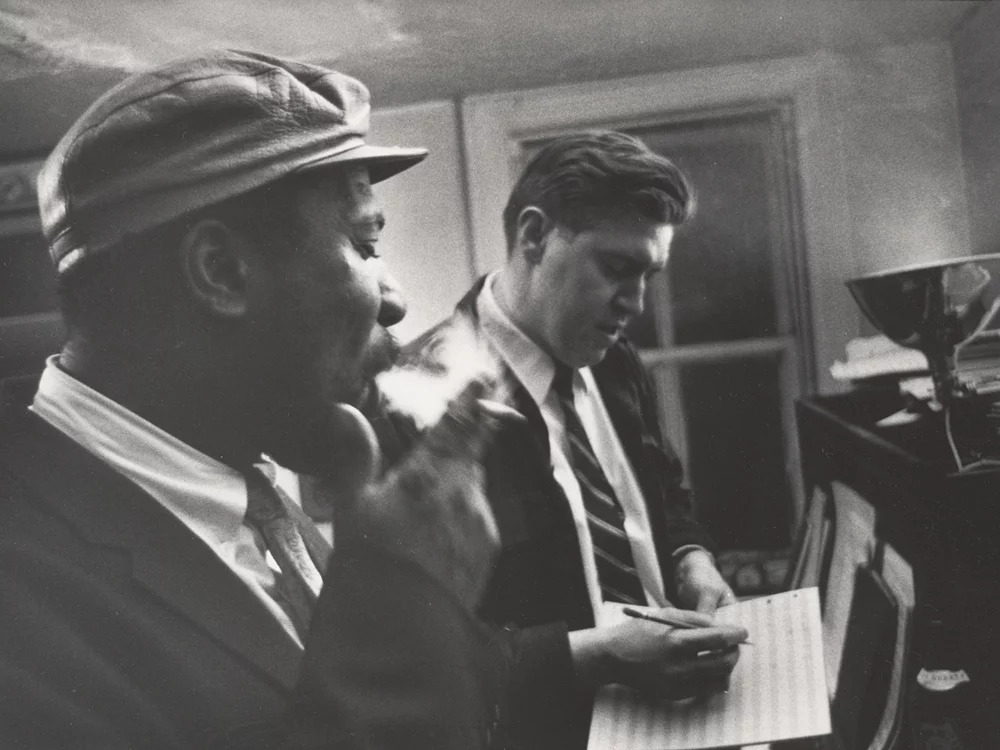

From a 1961 recording with two names on the cover : Thelonious Monk is on piano and John Coltrane on tenor saxophone. They are accompanied by Wilbur Ware on bass and (for this tune) by Shadow Wilson on drums.

Ruby, My Dear, Thelonious Monk with John Coltrane

That dear Ruby is supposed to be Ruby Richardson, Monk’s girlfriend when he was a teenager. Presumably he had composed this tune then.

The recording Monk’s Music, from which we already listened to Well You Needn’t also featured Coltrane, but only Hawkins was credited on the front cover. In any case, both musicians are on peer on this recording of this superbly sweet and tender ballad.

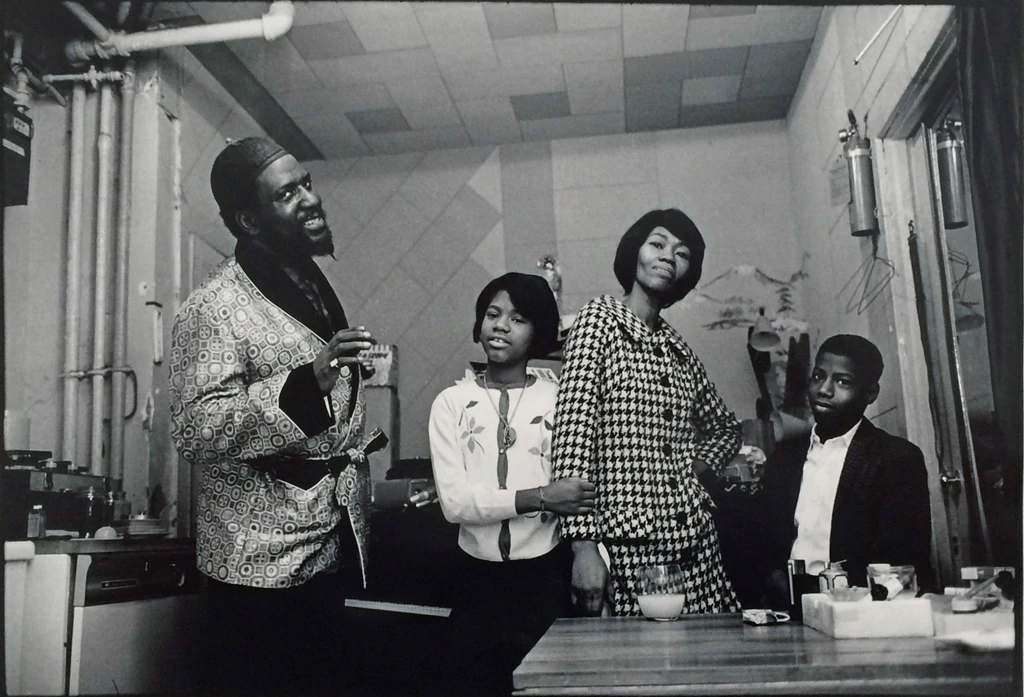

This recording was actually recorded in July 1957. Miles Davis had just fired Coltrane because of his drug addiction, and Coltrane and Monk happened to play together a lot, in particular many sessions at the Five Spot Café as on the picture below, where Wilson is on the drums, but Ahmed Abdul-Malik is on bass. They would also play at the Carnegie Hall in November of that year. The disc has only been issued in 1961, when Coltrane was a star.

John Coltrane, Shadow Wilson, Thelonious Monk, Ahmed Abdul-Malik. 1957 at the Five Spot Café

Regarding the arrangement, it is really a dialogue between piano and saxophone. On brushes, Wilson brings a homogeneous texture with few — if none — cymbals, and Ware’s bass often plays quarter notes along with the piano, or shorter intervals in the silences left by the melody.

Two bars of introduction on the piano, and the melody starts. A classic 32 bars, AABA structure. Listen how the melody, a very simple phrase on the saxophone, is reinforced by a chord progression on the piano.

After one exposition of the theme, Coltrane plays a chorus, staying quite close to the melody, especially for the bridge, and Monk takes a chorus on the first two As. Then, Coltrane comes back for the bridge and the final A, a coda on the piano, a final note and thats it!

Here, performed in 2021 “at Emmet’s Place”, by Emmet Cohen on piano, Joel Ross on vibraphone, Yasushi Nakamura on bass and Kush Abadey on drums.

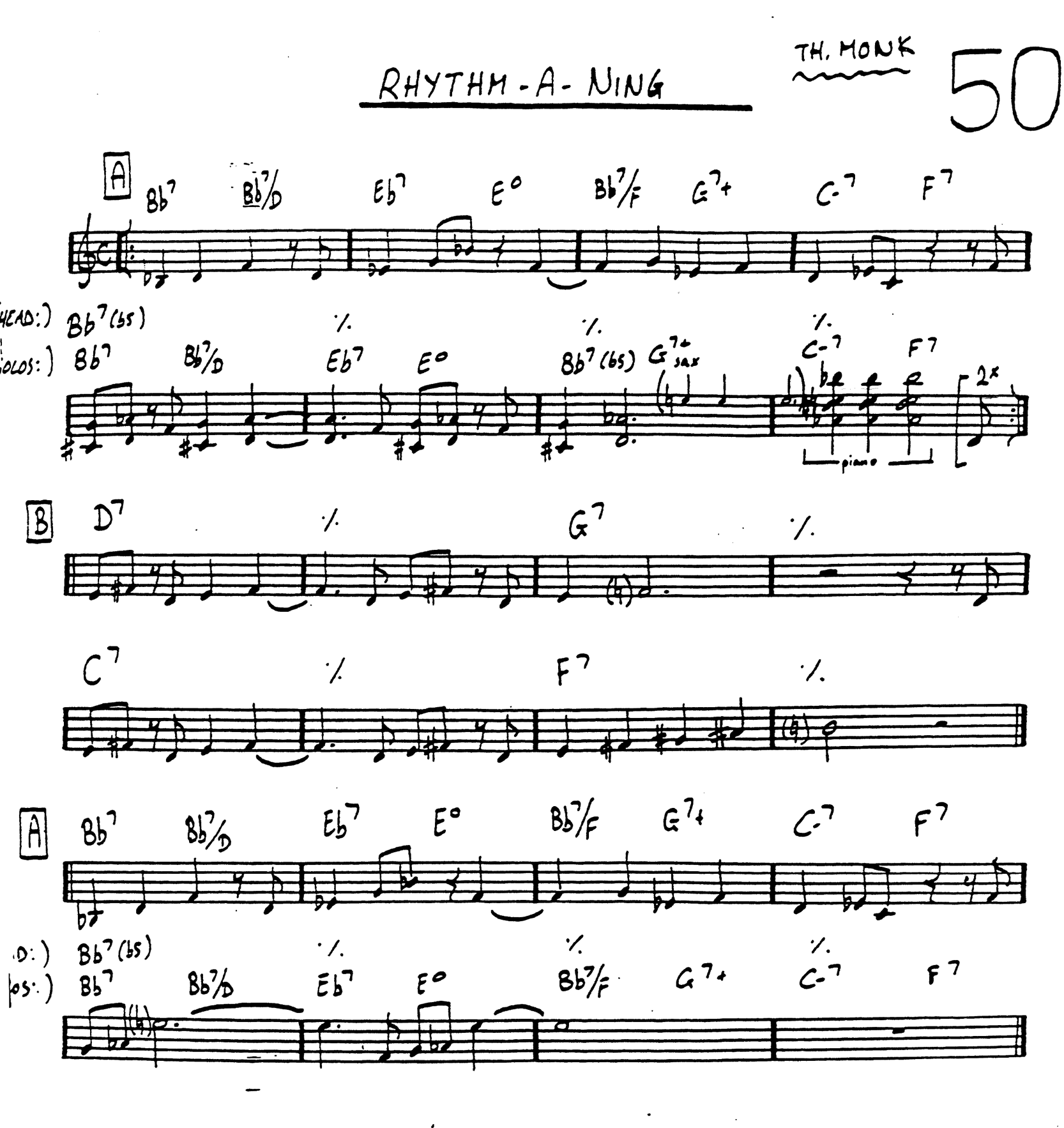

Rhythm-A-Ning, Emmet Cohen with Joel Ross, 2021

Among all forms of jazz tunes, this one is a classic among classics. 32 bars, AABA, “Rhythm changes”, meaning it borrowed the chords from Gershwhin’s 1930 tune “I got rhythm”. Hence the title, of course.

For the exposition of the theme, piano and vibraphone share the lead, A for vibes, B for piano. Then comes a first vibraphone chorus where you can clearly distinguish the A and the B (this is where the piano puts in the chords, every 2 bars). At start, bass and drums accompany very freely, but from the 3rd chorus on, they’re swinging like in hell. I lost count. Anyway, the piano gets in, putting some chords, like if it were Monk’s car honking — this modern post-bop is so exciting! At the end of Ross’s chorus, we clearly hear the melody again and, all of a sudden, at 4:44, the music stops for a piano chorus in a totally transformed atmosphere! Space… silences… quietness… Progressively, Cohen will put in more and more energy…

Solo bass chorus at 8:40 with only a few chords on piano. (I can’t comment on this, sorry…) The bass chorus ends with the melody and it is time for a drums solo. Abadey plays melodic lines — at 11:40, you can even recognize the melody! He plays it once more to announce the end of his chorus. Ross goes back to his vibes, everybody sings the melody once more, and that’s it!

Thelonious Monk is on piano, Al Blakey on drums, Milt Jackson on vibraphone, Sahib Shihab on alto saxophone and Al McKibbon on bass.

An early recording from the time where music was issued in 2-track 78 RPM discs.

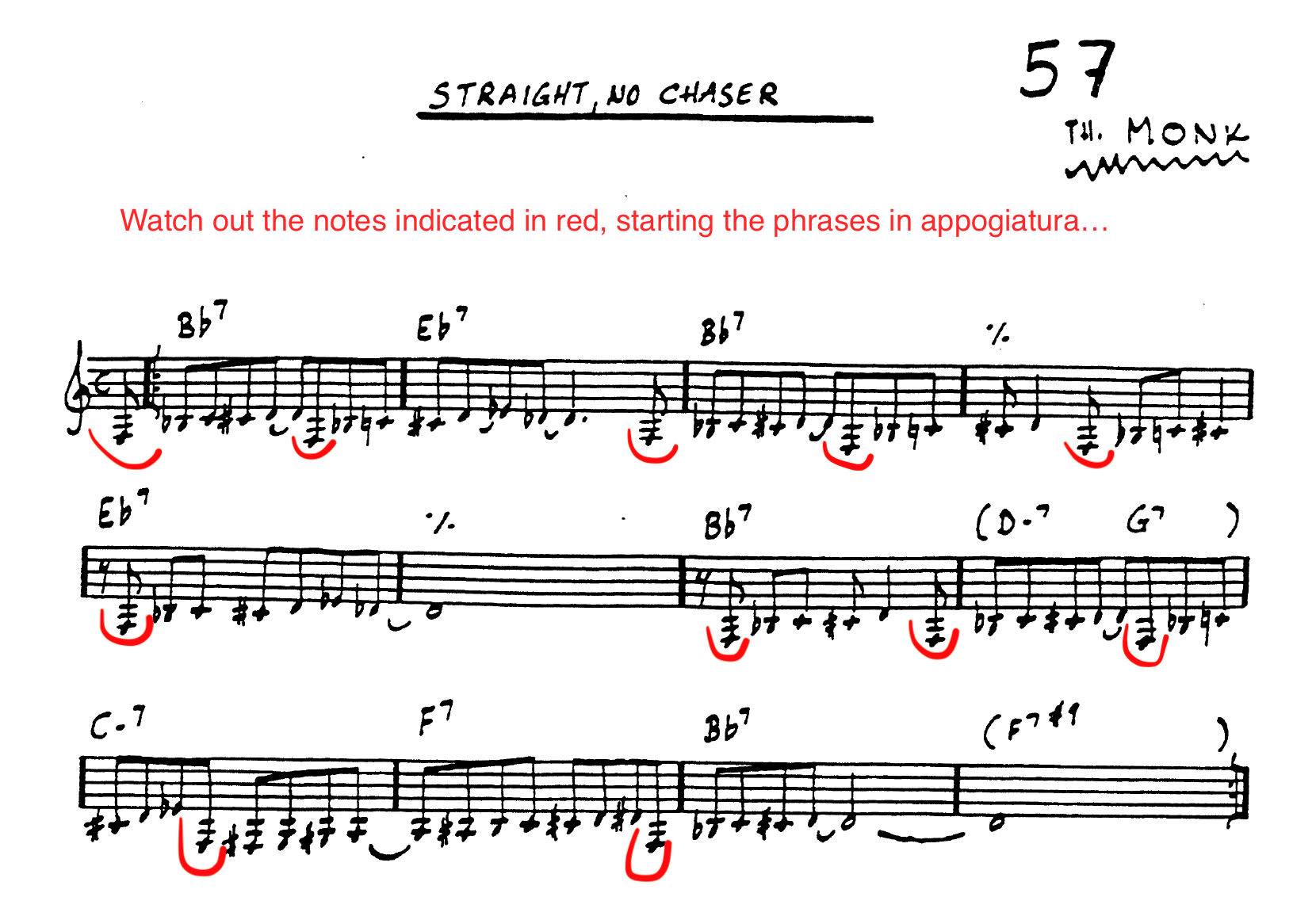

Straight, No Chaser, Thelonious Monk Quintet, 1951

This title is an iconic Monk one, and it will serve as a title for many recordings (by Monk himself in 1967, Joe Henderson in 1968), and for a documentary movie by Charlotte Zwerin in 1988.

A blues, meaning a very standard 12-bar chord progression built on the following pattern (each letter means 2 bars):

A A

B A

C A

Here, A = [Bb7 Eb7], B = [Eb7 Eb7] (small modulation), and C = [C-7 F7] (modulation that brings back to A).

However, Monk twists the form via the rhythmic phrases he composed. The overall structure of the theme is two 6-bars phrases, each one made by the repetition of a 3-beats phrase that shifts over the 4/4 ryhthmic structure. You can watch this on the score, searching for the the lower 8th note that starts the phrases just before a beat (this is called appoggiatura). I’ve marked them in red below, and see how they are each one beat earlier.

There’s one more trick: the second part of the tune, on measure 7, starts almost like the first part, except that it starts one beat later. This makes a difference between the two parts, but it is also extremly tricky to play if you don’t know the piece well.

This version is played in a quite straightforward way. It opens with a 12 bar chorus on the drums where Blakey makes you already feel the rhythm of the melody. (This makes a difference with a lot of the later recordings that apparently almost start with Monk on piano.)

A first exposition of the theme with piano and rhythm section, and a second one with saxophone and vibes. Two piano choruses (ending with something reminding me of Misterioso), one sax chorus, two vibes choruses, and two expositions of the theme to have it done.

It had to be short, because 3 minutes was the max that fitted on one side of a 78-rpm disc! And enjoy how Sahib Shihab’s sax solo is concise, but so articulate.

It’s hard not to feel that the title’s theme, Straight, No Chaser, when you want your whisky pure, without soda, is appropriate to this version.

The barytone saxophone player Claire Daly dedicated a full recording to Monk’s music and that version launches the festivities.

Mary Ann McSweeney is on bass, Peter Grant on drums and Steve Hudson on piano.

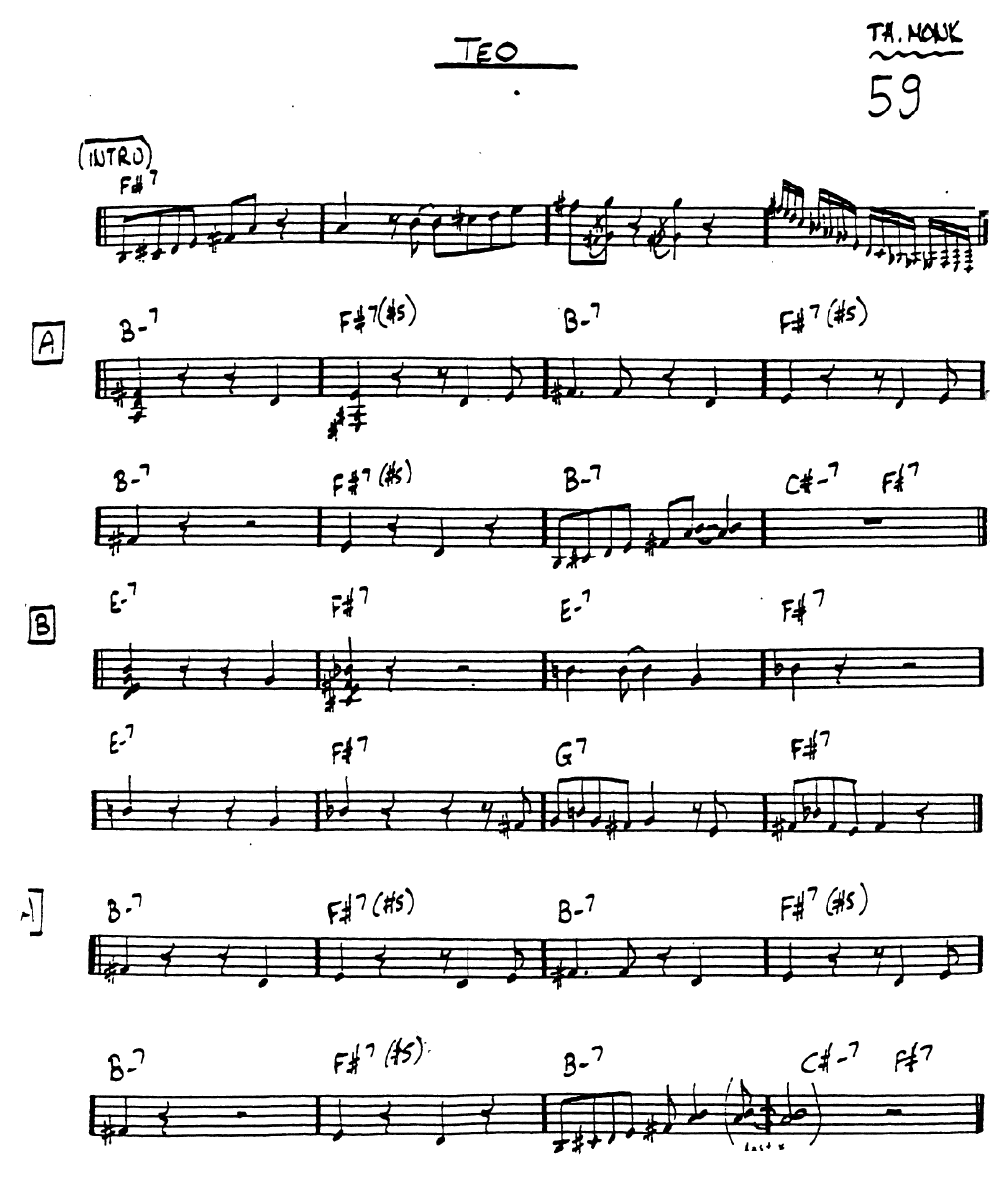

Teo, The Claire Daly Quartet, 2012

A less classic form, this tune has 24 bars, 3 phrases of 8 measures, ABA (the As are B minor, the B is played in E-).

Here, Claire Daly skips the introduction and starts right away with the melody, accompanied by her rhythm section. It works quite well, the mood is more “swingy” than what Monk has us used to. She goes on with two choruses on barytone, the first one stays close to the theme and the second one adds more variations. Listen how the rhythm section accompanies in a different way the A and B parts. Nice bass chorus then, where Mary Ann McSweeney starts from the melody, with little piano accompaniment (the drums are quieter too). After a piano chorus, piano and drums trade in 8 — 8 measures on the drums, 8 measures on piano, etc. 6 times so that the whole game covers the theme twice. Then it’s time to listen to the melody again.

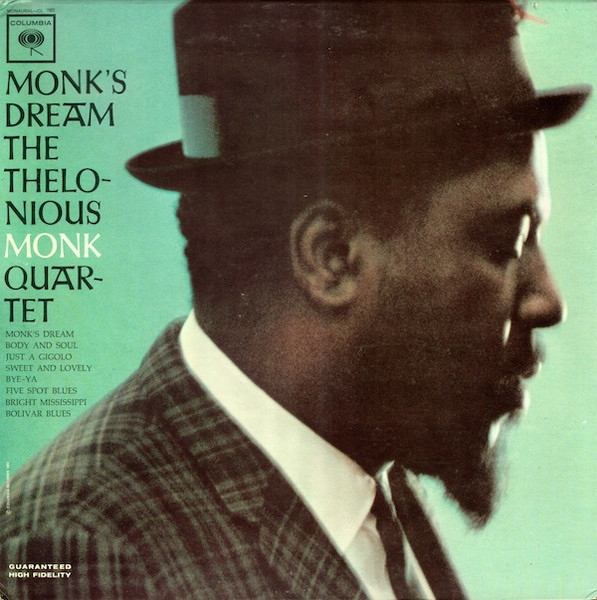

Although this song of Thelonious Monk does not seem too well known to me, the name of Teo is a very important one in the history of jazz recording — It is the first name of the composer Teo Macero, also a long time arranger and producer for Miles Davis. One can also find his name as the author of the liner notes for some recordings of Thelonious Monk, such as Monk’s Dream (recorded for Columbia, 1963).

From a live recording at Lincoln Center, 30 December 1963 with big band and quartet, arrangements by Hall Overton.

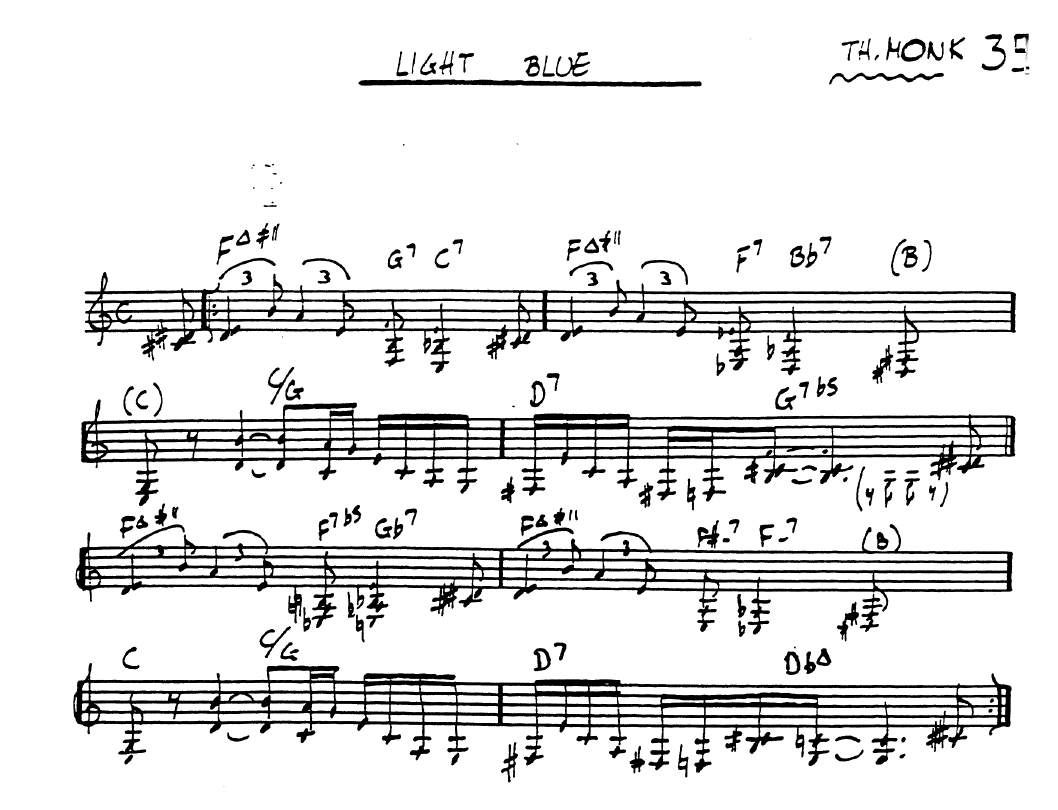

Light Blue, Monk Big Band and Quartet in Concert, 1963

Besides Thelonious Monk on piano, you can listen to Phil Woods, Gene Allen, Charlie Rouse on saxophones, Thad Jones on cornet, Nick Travis on trumpet, Eddie Bert on trombone, Butch Warren on bass, Frankie Dunlop on drums.

That tune, which was omitted from the first release of the concert, is a simple 4-bar phrase in F that is repeated twice. The first time, it ends with a G7b5 chord to relaunch, and ends in F-. There are small additional variations in the harmony.

It’s hard to know what to do with such a tune, and all these great guys seem a bit awkward. That won’t swing much and interactions will be scarce except when specifically arranged. Monk plays the first theme alone, then the band comes in for 2 themes. 5 choruses of saxophone (I don’t know which, probably Rouse), you can listen how Monk’s accompaniment switches progressively from playing the melody to playing nothing. 6 choruses of cornet (or trumpet?), I hear some phrases on clarinet around 3:48, the last chorus starts by recalling the basic melody. And we’re in for 6 sax choruses in which one every two choruses is accompanied by a big band arrangement of the melody (written by Overton).

At 8:24, it’s up to Monk to improvise for 3 choruses that will stay close to the melody. At the beginning of the 4th one, it seems that Monk will play something different, but then the bass player starts his chorus and Monk will leave him the focus. The 2nd bass chorus sticks to the melody, the 3rd one deviates, and the 4th one will end up with the melody again. It’s time to tell the melody a few more times, first on the piano, then the big band twice. At the end, the piano only honks some chords, and the tune finishes with an applause and a drum roll…

The Hudson river is the river which is flows west of Manhattan island, between Manhattan and New Jersey where Thelonious Monk ended his life, at Nica de Koenigswarter’s place where she happened to live after 1958, when her NYC neighbors were absolutely fed up with the noise and music of all the night-birds she hosted generously. You have to imagine that place, full of cats — because the baroness had many of them.

And, at the end of his life, a big cat - Thelonious - who reportedly hated the smaller ones, nevertheless is shown here holding a Siamese.

Monk first recorded this song in 1957. I like to imagine he wrote it about this new place that Nica bought for all the musicians who were her guests, but I can’t be sure. And certainly he wouldn’t know yet that he would live there from the mid 70s on.

It is a complicated tune, because nothing is standard in its the form. If you look at it from far away, you imagine , seing these 3 even lines, that it can be a blues. But let’s count the bars: A has 5 bars, B has 3½ bars (see this 2/4 measure at the end?) and A 5 bars again. So 13½ measures, while blues is 12.

The harmony is not that of a blues, neither.

And the melody starts on beat 2.

A pretty awkward form on which it is difficult to improvise.

The version I propose you to listen today is a modern one, by the New Monk trio of Laurent de Wilde on piano, with Donald Kontomanou on drums and Jérôme Regard on bass. Recorded in 2017, on the occasion of the 10th birthday of Thelonious Monk.

They take this tune from the 50s and use their natural time machine to move it to a radically different place so that it is even difficult to recognize the initial melody. I don’t dare proposing a detailed analysis.

Laurent de Wilde, Coming on the Hudson, New York Trio, 2017

Just enjoy the groove of the piano, the extraordinary melodic bass lines, and the inventive accompaniment on the drums. The time signature has switched from a swinging 4/4, with emphasis of weak beats 2 and 4 to kind of march that emphasizes beats 1 and 3. You will also observe, maybe, and if I’m not wrong myself, how De Wilde plays with parts of the melody that don’t look so important, beats 3-4 of measure 3 and 1-2 of measure 4, and repeats this pattern all over the drum solo, putting the focus on a negliged part of the melody.

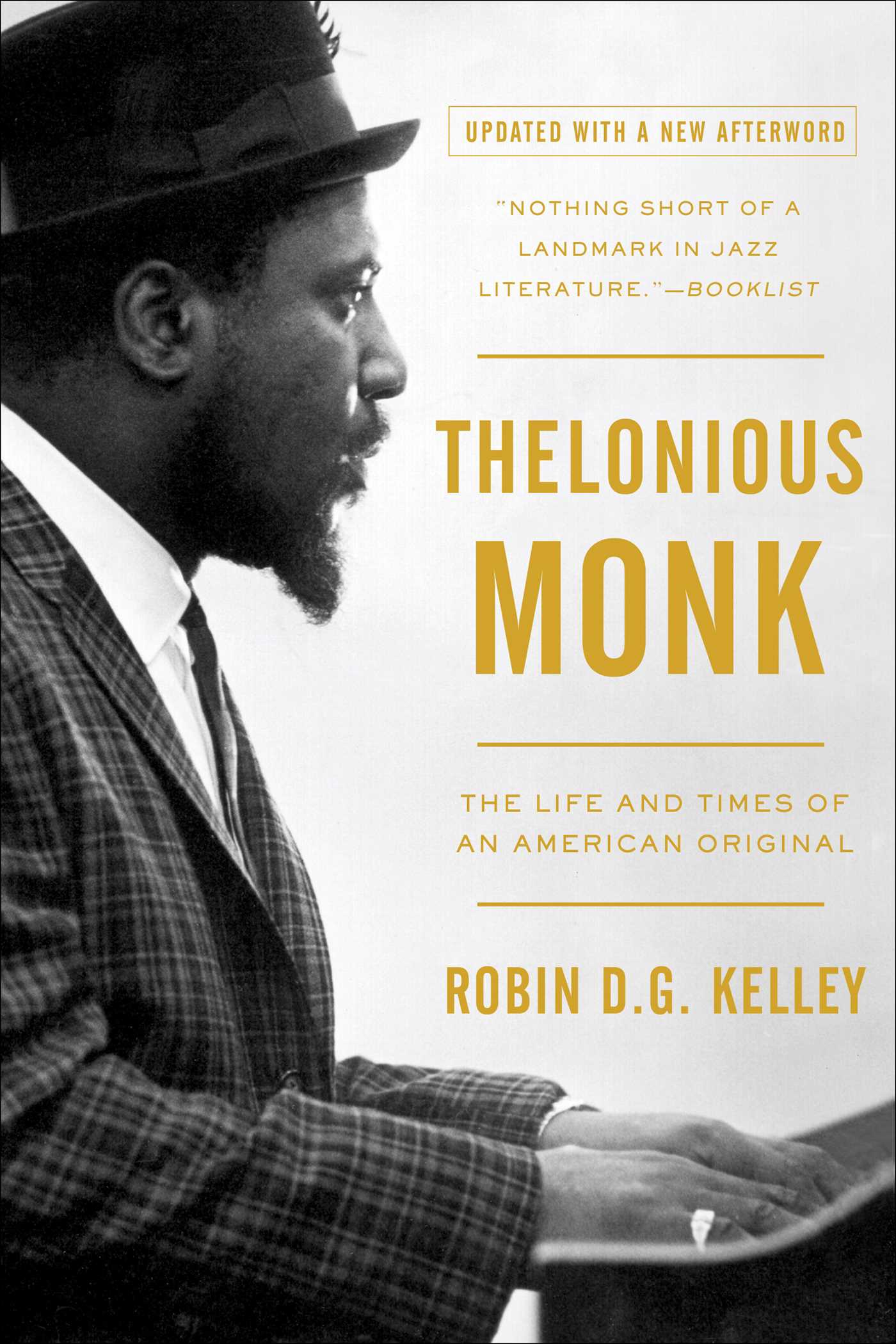

Finally, recall that Laurent De Wilde is not only an excellent piano player and improviser, but also a superb writer. His biography of Thelonious Monk — simply entitled “Monk” — is extremly interesting. With enlightening reflections on music and what it meant to be Monk.

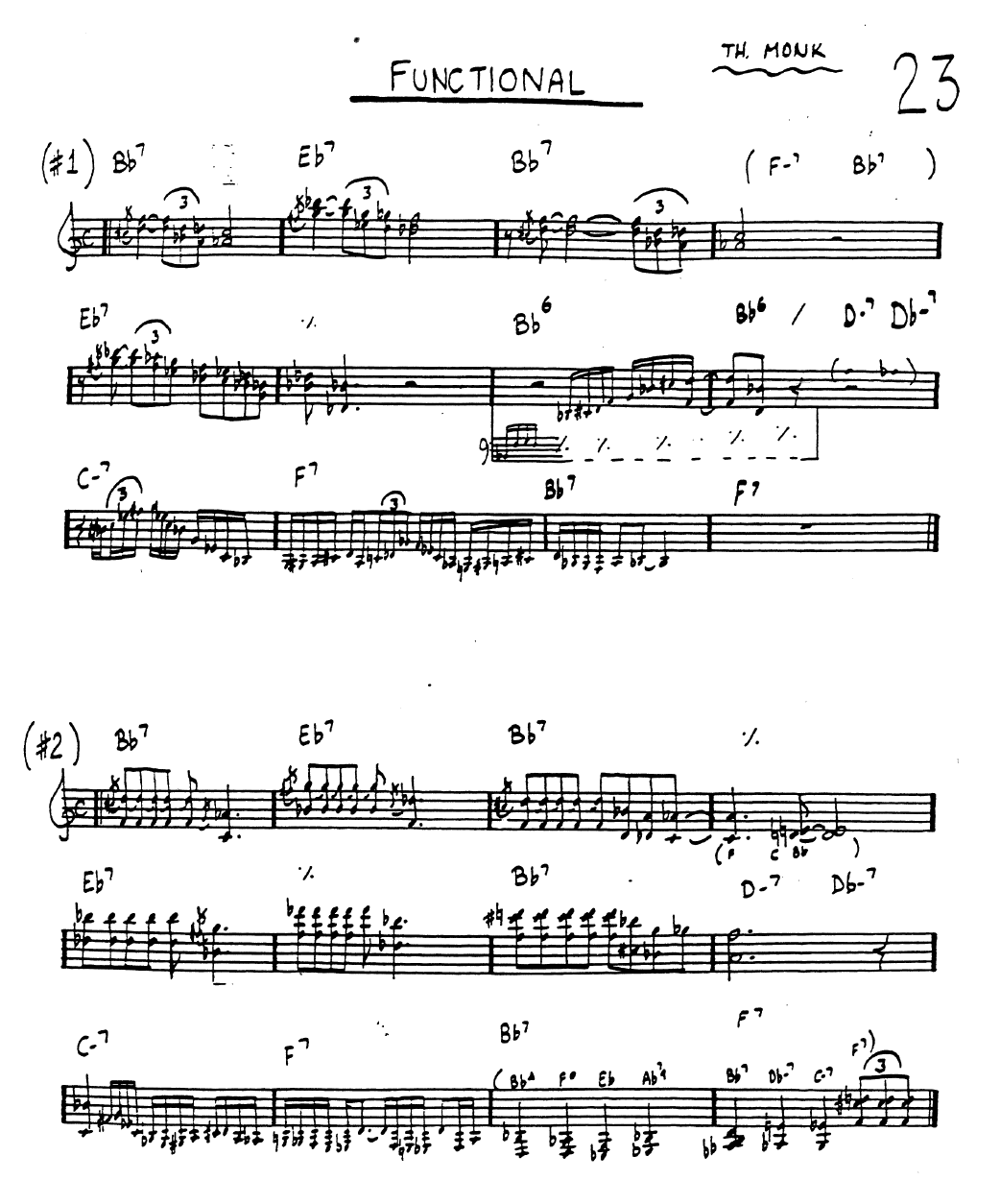

In 1957, Thelonious Monk recorded a full solo album, “Himself” that contains this nice and quiet blues.

Functional, Thelonious Monk, 1957

It is actually two blues that the fake books describe as this tune. In this version, Monk starts with #2, the second theme he plays incorporates some of #1.

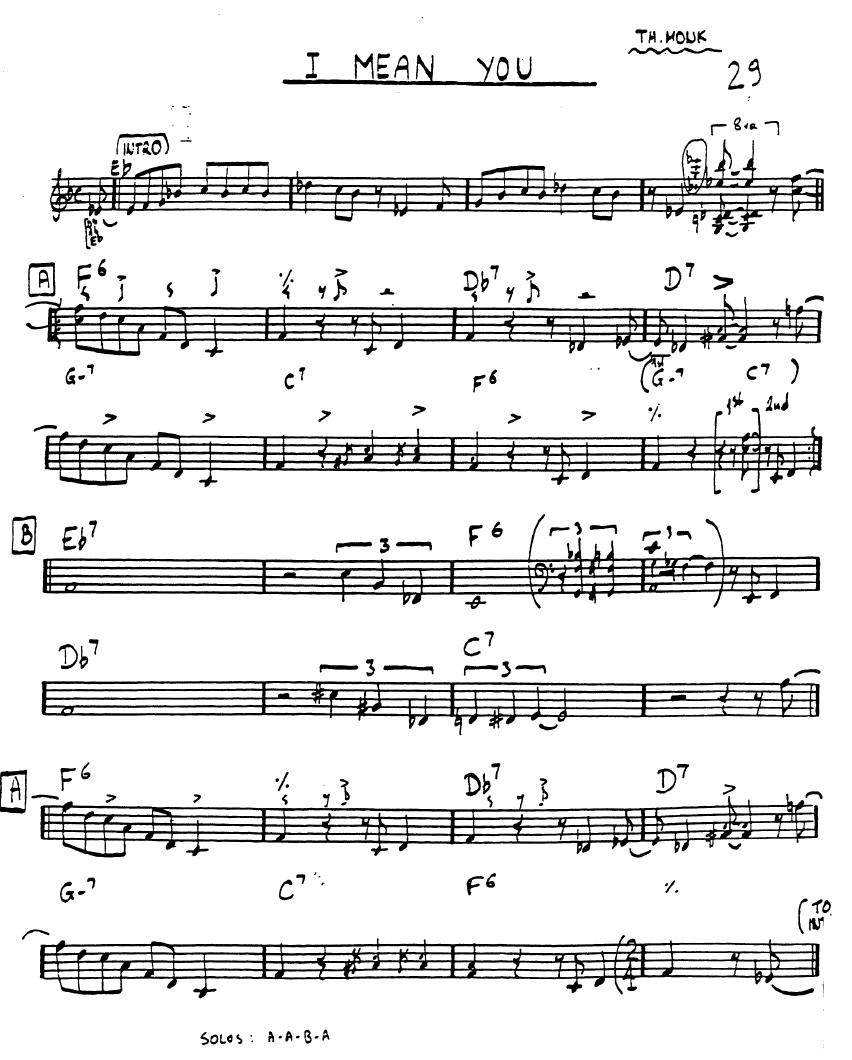

A wonderful trio : Kenny Barron on piano, Kiyoshi Kitagawa on bass, Brian Blade on drums.

Kenny Barron Trio, I Mean You, 2006

There’s something very nice that can be felt even before the music starts: The pulse will be given by Kitagawa, who snaps his fingers, and I find incredible how he manages to make us feel the time in such a crisp and precise way.

32 bars, AABA, with a 4-bar introduction, that’s what is written. Funnily, while the main melody goes down, the one of the introduction goes up.

In their introduction, they start by repeating the introduction 4 times, with each time a 4-bar answer by Brian blade. Exposition of the theme by the band, introduction phrase again, piano choruses and bass choruses — very melodic ones. They go on by trading eights between piano and drums, and retake the melody again, and they conclude with the introduction phrase !

Once again, a Thelonious Monk tune whose structure has a standard form, 32 bars, AABA, in which Monk will surprise you by his rhythmic phrases.

Thelonious Monk (piano) and John Coltrane (tenor saxophone) share the lead, Ahmed Abdul-Malik is on bass, Shadow Wilson on drums. This was recorded live, 29 November 1957, at Carnegie Hall, NYC.

Bye-Ya, Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, 1957

As often, Thelonious Monk presents the first phrase of the melody alone, and then the band starts by exposing the theme. Listen how the melody takes its leap by these two notes A-Db placed on beats 4 (appogiatura) and 1, and then another syncopation, but then Monk displaces this figure of two quarter notes by one half-beat at measures 5/6 and 6/7, and falls back on the beat at measures 7/8.

Thelonious Monk, Bye-Ya, score

It is up to John Coltrane to take the first four choruses. Although it is only a few years later that he will become definitely famous, his sound, the fluidity of his dense phrases can already be felt.

Then Monk takes three choruses. The first one is astonishingly full of silences, borrows some phrases from other tunes, at a point where it is a bit difficult to keep track of the pulse. The second chorus is closer to the melody, and the third one goes to yet somewhere else.

The band gives a final exposition of the theme. You can note, if you hadn’t already, how Wilson accompanies the tune: on part A, he only plays on tom-toms, with a kind of afro-cuban drumming, while part B is pure swing — and well thought-of transitions !

At the end, the final 2 bars are repeated once more, and Coltrane repeats the closing movement C-Eb, the drum rolls, and that’s it! Bye-Ya!

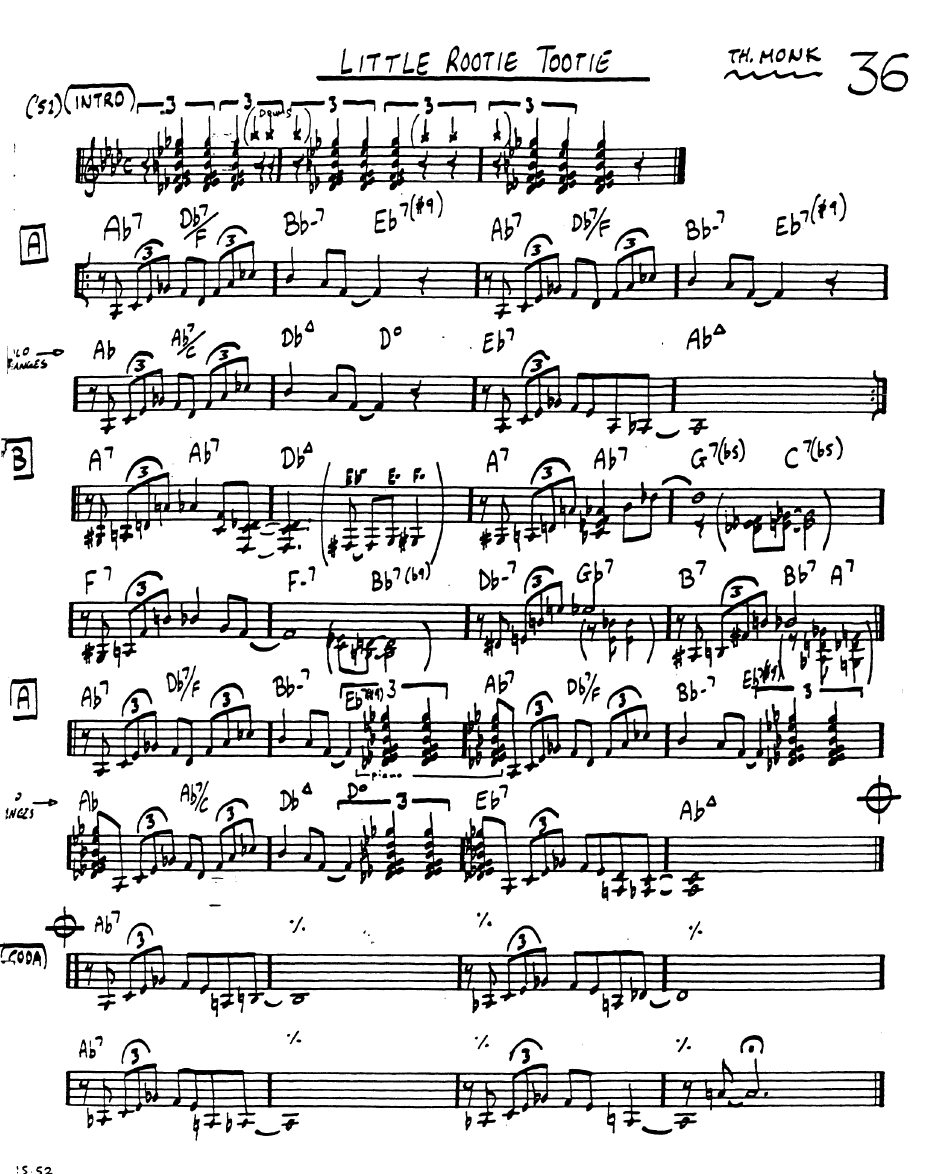

It’s Monk’s son, T S Monk, on the drums, with an incredible big band, Ron Carter on bass and Danilo Perez on piano.

Little Rootie Tootie, T. S. Monk, 1997

hat was recorded 1997, the recording’s name is “T S Monk on Monk”.

This tune Little Rootie Tootie was first recorded on October 15, 1952 and was named for Monk’s son, Thelonious, Jr., who was two years old at the time. He earned the nickname “Toot” after “Little Toot the Tugboat” from a favorite Walt Disney cartoon; young Thelonious learned to whistle-like “Little Toot” before he learned to talk. (I owe this information to the Thelonious Sphere Monk website.)

Borrowing the classic AABA form, the song strikes at once with the dynamic rhythmic figure that is repeated again and again along the theme.

It also features a cheerful introduction, made of displaced half notes triplets (ending on the beat), and which the brass section will make you hear to sustain the energy of the thee band. On the A parts, TS Monk uses an afrocuban clave, while he swings on the B. After the theme, you are blessed with three long solo sections, by Danilo Perez on piano, Grover Washington Jr on saxophone, and finally Roy Hargrove on trumpet, accompanied by rich arrangements of the brass section. A final theme, they play the coda and it’s done!

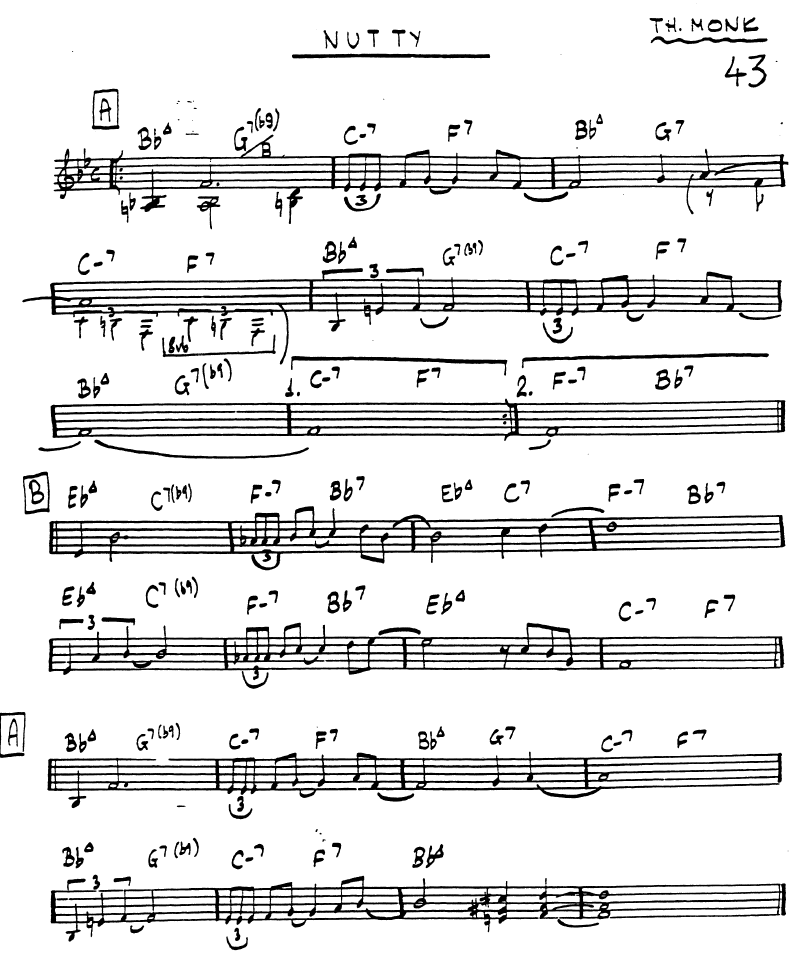

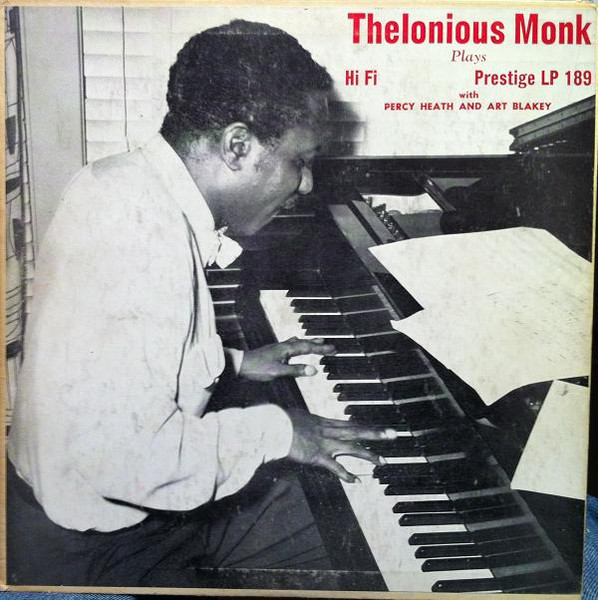

A 1954 trio recording with Thelonious Monk on piano, Percy Heath on bass and Art Blakey on drums. This take had been reissued in the 1956 Prestige recording that indicates Thelonious Monk and Sonny Rollins on the cover, but it also contains trio and quintet pieces.

Nutty, Thelonious Monk Trio, 1954

This is a simple AABA form, modulating from Bb to Eb on the bridge, and Monk performs it, I feel, with more bluesy intonations than what he would do a few years later.

Introduction at the piano with some notes on the bass, and then Monk exposes the theme. Listen how the figure that Heath plays on bass gives a dancing atmosphere — on Monk’s chorus, he will switch to straight walking lines. Monk plays 2 choruses and one half, and Heath does the second half. Then comes a nice drums chorus, where Blakey plays a lot of toms, without the strand that gives the snare drum its metallic sound. He regularly indicates 2 and 4 on hi-hat during the A part, and triplets on B. After that comes a new piano chorus, and a final theme that ends all by itself, without the need of a coda.

Paul Motian and the electric be bop band, with Paul Motian on drums, Anders Christensen on bass, Steve Cardenas (left) and Ben Monder (right) on guitar Chris Cheek (left) and Pietro Tonolo (right) on saxophones

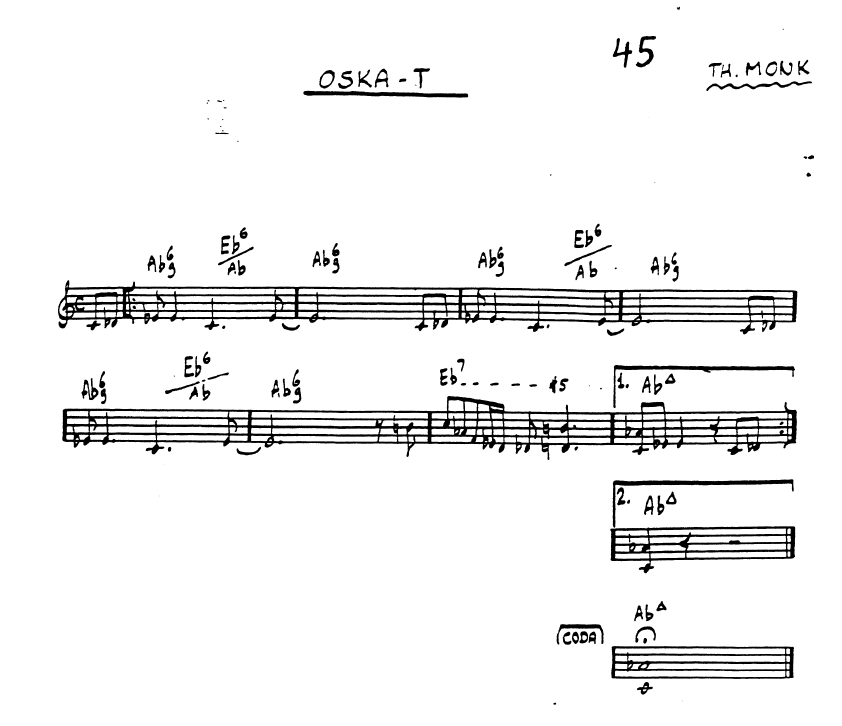

Paul Motian and the e.b.b.b., Oska-T, 2001

There isn’t really a melody, just an 8-bar riff which the band will play many times. Twice on guitars, then the saxophones come in and play it twice. And twice more one octave higher. And twice on drums only.

There are two explanations for the title’s song. One is a hommage to Oscar Treadwell, a Cincinatti DJ and radio host to which Charlie Parker at written a tune — “An Oscar for Treadwell”. See what the WVXU radio wrote for him 10 years after his death in 2006.

Another explanation might be that it’s a contraction for “Ask for tea”.

In any case, the tune was composed in 1963 (for the Carnegie Hall big band concert, with a 9:21 version!) and, pianist Ethan Iverson says, this one-chord tune might be Monk’s answer for the then everywhere modal jazz.

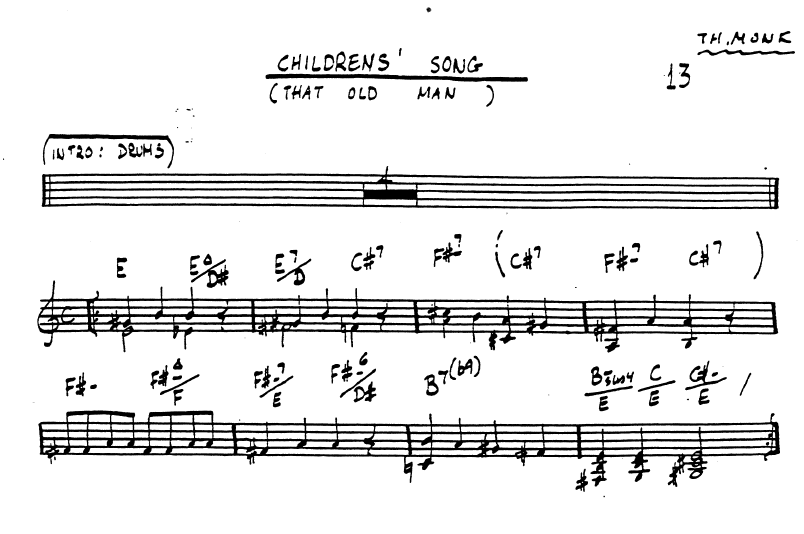

Here, performed by Thelonious Monk, Ben Riley on drums, Charlie Rouse on saxophone and Larry Gales on bass.

Thelonious Monk Quartet, Children’s Song (That Old Man)

Rareley enough to be noted, the tune begins with an intro on drums. And then the melody begins. A small “children’s song” on 8 bars (played twice) which is played in an overly childhood manner. Inspired by an children’s song called That Old Man.

Donny McCaslin on tenor saxophone, with John Swana on trumpet, Steve Cardenas on guitar, Scott Colley on bass, Gene Jackson on drums.

Donny McCaslin quartet, Eronel

I was introduced to Donny McCaslin by another route than jazz, namely Bowie’s final album Black Star. You may have recognized Cardenas’s sound at the guitar, for we already listened to him in Paul Motian’s ebbb. Of course, Jackson sounds less free than Motian.

Here, the band plays it in a quiet mood, syncopation and dissonances are freed of all aggressive intention. The structure is clear. Introduction/Theme/Sax, guitar, bass choruses (with many quotes from the theme)/Theme, ending with the Introduction.

Wikipedia says that this 32-bar AABA composition is not due to Monk alone, it is based on a composition of pianist Sadik Hakim and trumpet player Idrees Sulieman, two bop jazzmen. Eronel is Lenore — the name of Hakim’s girlfriend — written backward.

Of course, Monk changed a lot of things, added the bridge, and put his name on top of the score.

This is a 16-bar AABA tune (hence its title), preceded by a 4-bar intro of one bar piano solo, one bar drums solo and 2 bars bass solo (played twice).

The version I propose for today was recorded in 1952, in the middle of the bebop era, with Thelonious Monk on piano, Kenny Dorham on trumpet, Lucky Thompson on tenor saxophone, Lou Donaldson on alto saxophone, Nelson Boyd on bass and Max Roach on drums.

Sixteen, Thelonious Monk quintet, 1952

The melody is extremly simple, with essentially one noticable figure, syncopated, that is announced in the introduction, and played on the first bar of the A part, and hinted to on the second bar of the B part. (The rest is made of arpeggios…)

After the introduction, the melody is played once. Then the various solists sing a few choruses (Donaldson, Dorham, Thompson, Monk), and we’re back to the theme which ends abruptly in the middle of the last bar.

It’s the weekend and we need a beautiful ballad to bring us rest and peace. That one is taken from a slightly unusual duet recording by two avant-garde improvisers, Dan Tepfer on piano and Ben Wendel on saxophone.

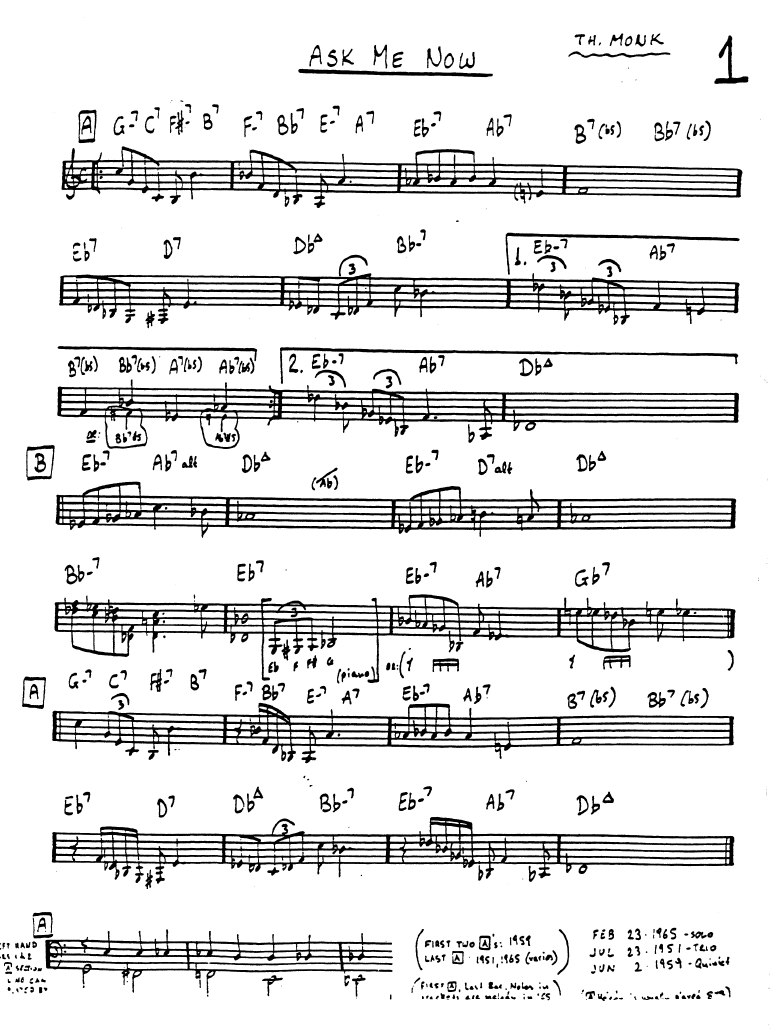

Ask Me Now, Dan Tepfer & Ben Wendel, Small Constructions, 2013

If you look at that album cover, called Small constructions, you’ll see a bunch of other instruments, a guitar, a bassoon, a few saxophones and a melodica… Because these two guys used recording techniques to play all of this.

Both instrumentists are particularly fond of duets. From Ben Wendel, please listen to his Seasons, twelve tunes, one for each month, that get their inspirations from the season, but also from the jazz repertoire, and each one recorded with another musician. The original work is to be listened to on YouTube, although he published a quintet version of it later on.

As for Dan Tepfer, his duets with Lee Konitz were absolutely fabulous.

But back to today’s tune, Ask Me Now. 32 bar, AABA form, what makes it relatively unusual is his first two bars of the A — whose harmony goes down from G- to F- (using classic II-V-I movements) until it reaches the Eb- at which the rest of the piece will remain.

The theme is exposed calmly on the saxophone, at a very slow tempo, that is sometimes wonderfully stretched, with a few variations and a simple piano accompaniment. Then Tepfer plays a chorus on the first two As, the harmony is played on the sax (and possibly a rerecording of a piano accompaniment). Sax chorus on the second part of the tune. They play a final A and conclude. This is so beautiful…

A quintet recording : with Thelonious Monk on piano, we have Thad Jones on cornet, Charlie Rouse on saxophone, Sam Jones on bass, and Art Taylor on drums.

Jackie-Ing, Thelonious Monk Quintet, 1959

Recorded in 1959 for Riverside, the recording’s title — 5 by Monk by 5 — refers to the fact that it contains 5 Monk’s titles played in quintet.

This tune was named after Monk’s niece, Jackie Smith. There’s an 2004 interview of her by the Bronx African American History project of where she tells the origin of it:

RG: I have a question for Jacque. Thelonius Monk wrote a tune called Jacque-ing.

JSB: Yes.

RG: Was it named after you and dedicated to you?

JSB: Yes.

RG: How did that come about?

JSB: I don’t know. I was at his house at 248 West 63rd Street and he played it a little — would play something he was writing. He didn’t have a title and then on a page — half of an 8 by 11 piece of paper he – in a spiral book – he wrote in a pencil Jacque-ing and that’s how he did it. Yes, yes.

RG: That’s very interesting.

MN: So you have a famous piece of music named after you.

RG: That’s right [laughs].

JSB: I always felt humbled by it.

It’s a 16-bar tune, almost in Bb, with a 2-5-1 progression on bars 7-8-9. It has a kind of lively march tempo (178 bpm on this version) and was used by Monk’s bands to make the opening of many concerts.

Thelonious Monk, Jackie-Ing, score

This take starts by 8 bars of Art Taylor, who plays a rigorous swing on the ride cymbal, with syncopations on the snare. Then cornet and sax play the theme (twice). On the second time, we start hearing some piano chords (esp. that on bar 4!). Charlie Rouse and then Thad Jones both take 6 choruses. Monk plays the theme once, plays no chorus and the band redo the theme twice as at the beginning, ending in fermata (point d’orgue) and that’s it !

Ravi Coltrane - Tenor & soprano saxophone David Virelles - Piano & Keyboard Dezron Douglas - Bass Johnatan Blake - Drums

This is a 32-bar piece, in ABAC form built on successions of ii-V-I movements with rapid scales that go up and down.

When I say rapid, you may be dubious, since it’s only a bunch of 8th notes. But they play that tune at the monstrously high tempo of 274 bpm… And they’ll play at that tempo for 13 minutes !

The introduction is kind of rubato, it’s hard to know what will happen until at 00:12, Ravi Coltrane takes the last 4 bars of the tune. And then you can hear the theme, but you’ll have it only once.

David Virelles takes 8 choruses. Honestly, I can’t understand what he does, chorus after chorus. At various points, one gets a hint at the theme, but they play with the time which gives me pain at keeping a precise count of the bars. But they do.

8 choruses by Ravi Coltrane. At various points, roughly every two choruses, he clearly marks the end of the chorus.

And then 6 choruses on the drums, or so it seems. Maybe one day I’ll be able to understand and transcribe this, but for the moment, that’s pure mystery to me… Except that from time to time, Johnatan Blake plays something that makes us hear the melody. And the last chorus is maybe the clearest (around 10:41, it’s obvious that Blake plays parts AC).

Then comes yet another incredible stuff, when Coltrane takes a bit of the melody and, again stretching the time, leads us to another few choruses, and then he plays the C, and that’s it!

You can’t imagine how much I cry of having to choose 9 compositions out of the remaining 37, for this 40-day challenge… So it will be a relatively unknown one for today

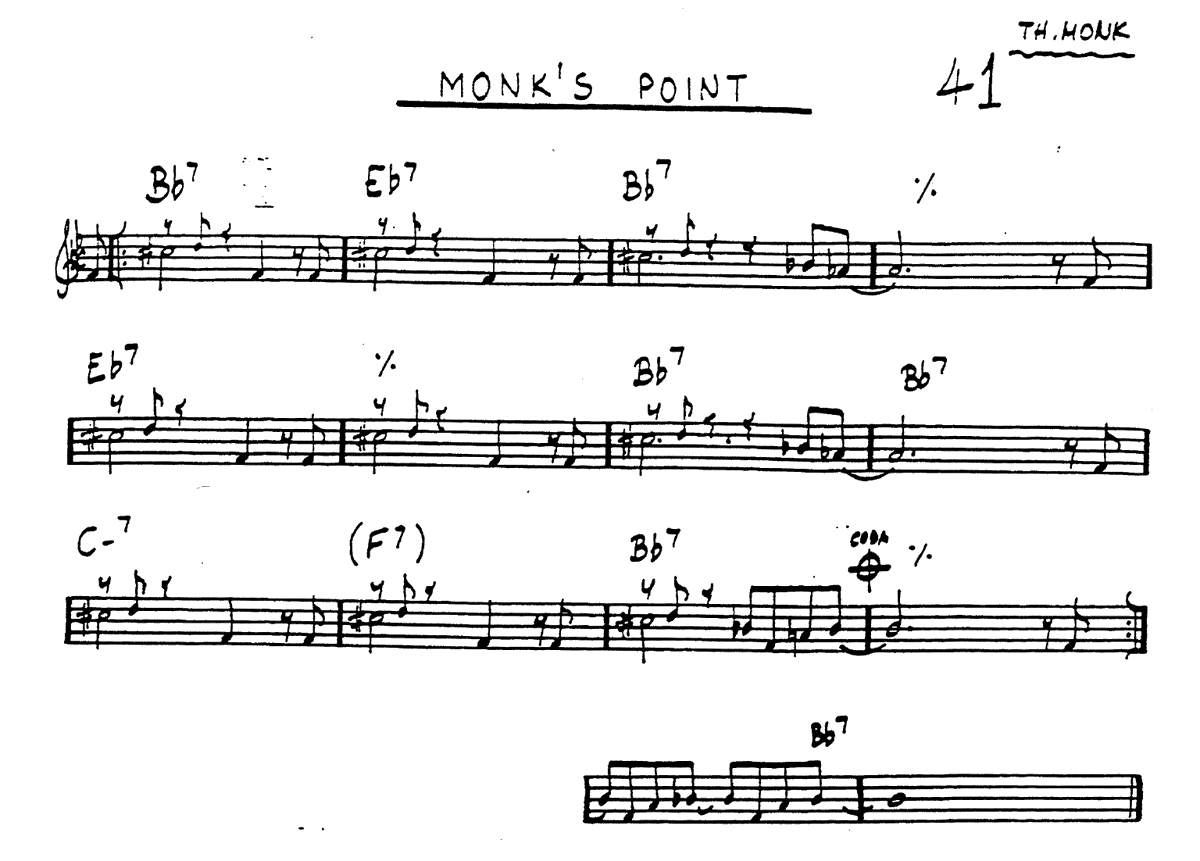

That’s a Bb blues, 12 bars whose harmony oscillates from Bb to Eb7 and resolves in a bluesy way through this ii-V-I movement of the last 4 bars. Very little notes, some syncopations, but it could really be some bland stuff…

Here, it is arranged for big band by Oliver Nelson, with Thelonious Monk’s quartet and Oliver Nelson’s musicians. Recorded in 1968, lively tempo (170bpm), east-coast sound guaranteed…

Monk’s Point, Thelonious Monk with Oliver Nelson’s orchestra, 1968

Oliver Nelson is a saxophonist, composer and arranger. His master piece may be The Blues and the Abstract truth, a recording with an extraordinary line-up.

The musicians play a 2-bar intro and the full band plays the theme twice, with energetic riffs on the second time. Then come 4 choruses by Monk where he plays the theme, but spreads 1 bar over 2. After a very present starting, this creates space and even quietness. One more theme by the brass section and Monk goes on with 2 more choruses, with brass riffs.

At 03:16 come 5 trumpet choruses (I don’t know who plays), Monk adds the melody on choruses 2 and 3, and the brass section adds riffs on choruses 4 and 5. At 04:43, it’s time for the sax chorus, presumably Charlie Rouse. The first chorus has a lot of drums, buut from the second one, the sound becomes distant, with a lot of reverb (I mean, a lot), the piano comes back, then the brass rifs. 06:43, two bass choruses by Larry Gales. Monk adds a few notes on the first one, plays the melody on the second one. (But that melody is minimalistic, so it doesn’t disturb the chorus at all.)

After that, the brass section gives one more theme, and a second one punctuated with riffs, a final riff, fermata!

From a 2009 recording, with Marc Ribot on guitar, Don Byron on clarinet, Nicholas Payton on trumpet, this is Allen Toussaint on piano!

Bright Mississippi, Allen Toussaint, 2009

Allen Toussaint was born in New Orleans in 1938 and is probably more known to you through his work with the New Orleans funk band called The Meters, those guys whose music set Fire to the bayou! This recording is in a more classical New Orleans jazz style, and you’ll see how well it fits Monk’s music. To be honest, I should tell you that this song, Bright Mississippi, is built on the rhythm changes of a very classic 1925 song, but I’ll let you guess which for a few tweets.

16 bars, played twice, with chords that go down in fifths: F7 - Bb7 - Eb7 - Ab. But this also gives the same harmonic bluesy 2-5-1 movement we’ve often heard: the F7 of the 1st line is the 5th degree of the Bb7 of the second line. This Bb7 can be viewed as the 2nd degree of Ab7, of which Eb7 is its 5th degree, and we land on Ab7.

After an introduction, the band plays the melody in a definitely New Orleans style, with guitar, clarinet, trumpet. The drum accompaniment by Jay Bellerose is typical of that style called “second line”. (Have you watched David Simon’s Treme?) If you wish, here is a link to a brief history of the second line brass bands.

After one theme (32 bars) on reeds, with a bit more piano on the second part, Toussaint plays one chorus (rythm’n blues style), Byron and Payton each share one half a chorus, and we get one for David Piltch on the bass. One more theme, with a clarinet improvisation on top of it, and an improvised question/answer conclusion by the clarinet and trumpet.

That was Bright Mississippi, a 1961 composition of Thelonious Monk played in New Orleans-style by Allen Toussaint and his band.

And if you found yourself humming Sweet Georgia Brown, cheer up that you recognized (and hopefully enjoyed!) this contrafact!

From a 1957 recording with the same title, with Sonny Rollins on tenor sax, Ernie Henry on alto sax, Oscar Pettitford on bass, Max Roach on drums and Thelonious Monk on piano.

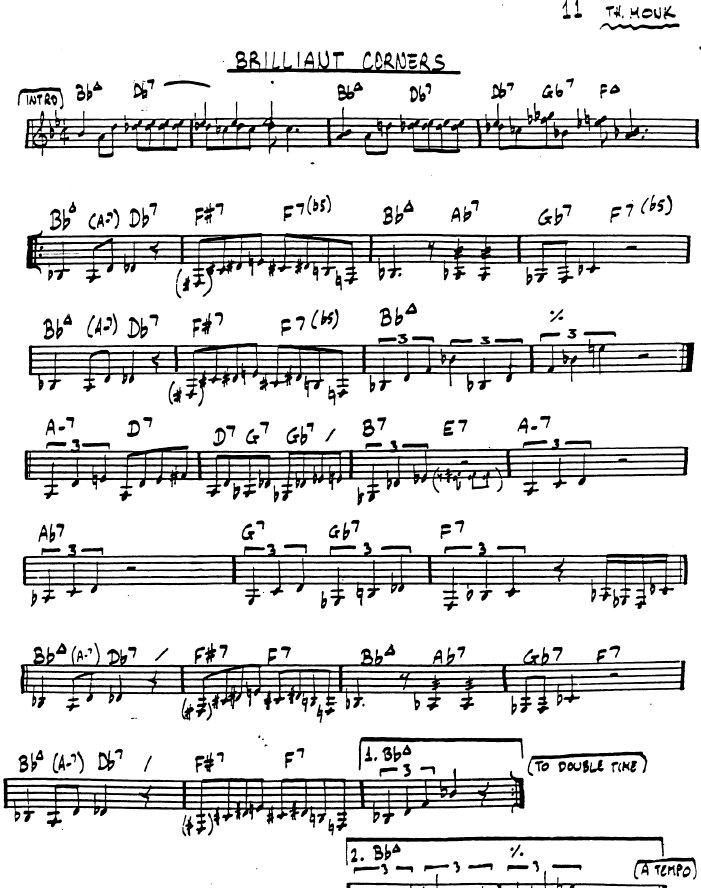

Thelonious Monk, Brilliant Corners, 1957

Melodically, the structure of the theme is ABA, played twice, but A has 8 bars, B has 7, and the second A has only 7 bars, which makes 22/23 bars. The main harmony is Bb for part A, while the bridge modulates…

After a solo piano intro by Monk, the musicians play the theme in a completely straight way, no swing at all, and no systematic rhythm on drums except that Roach uses the silences of the melody for interventions to reinforce this strange melody, especially during the left silences.

Heavy mood, moderate tempo (98 bpm) for the first theme, but the band doubles the tempo for the second one, and play it in a swing style. It is at once much more lively. They will respect this structure all over the tune.

Feet on the brakes, back to the initial tempo for the first chorus, Sonny Rollins on saxophone, and double speed for the second one.

hen two choruses on the piano. (I’m not sure that Roach is on track with Monk on bar 16, where Roach’s notes give a feel of the ending of the bridge, but Monk is already on the first bar of the A!

Alto sax choruses, and a remarkable chorus by Max Roach on the drums at 05:16. He will play on the melody all over his two choruses. No hi-hat on the first one, but you can definitely recognize where the bridge is — on the last 3 bars of it, he plays triplets of 8th notes, with an accent at the cymbal on the first beat. At the end of the first chorus, he plays the triplets of quarter notes that are characteristic of the end of the melody and starts for a second chorus, double tempo.

There, Roach will adds the hi-hat on beats 2 and 4, but his solo is absolutely gorgeous — both creative and faithful to the melody.

After a troubling silence, it’s time to go back to the theme, first time at slow tempo, second time at double tempo. And it ends abruptly.

History says that this complicated tune had been difficult to record and there are 25 takes of it, all on one day, October 15, 1956. Apparently, Rollins had been able to master the piece, but Pettitford and Roach had trouble, Pettitford complained that there were bars missing.

As told by Robin DG Kelley in his book on Thelonious Monk, the producer, Orrin Keepnews remembers that this almost went to fistfight between Monk and his bass player. The point is that Monk didn’t share scores of his music: “Like Duke Ellington, he genuinely believed that the best way to master a song is to learn it by ear”, Kelley writes. So what we just listened to is not one take of the tune but an edited version of those 25 incomplete takes! And I learned in that book that the troubling silence I had noticed after Roach’s solo was a glitch in the editing process…

A duet: Fred Hersch on piano, Will Vinson on saxophone This is taken from a double CD published by Vinson in 2020, one of them duets with pianists, and the other in quartet. That take was recorded in 2017.

Will Vinson, Fred Hersch, Work, 2017

32 bars, AABA. Lively tempo (180bpm). I won’t say much about this tune. What your ears will tell you will definitely be better than my rambling about the structure. You’ll have one theme, 2 choruses on saxophone (with piano accompaniment), 2 (solo) piano choruses, then the sax comes back for one joint chorus, they play the theme again and conclude.

The dissonances that are sometimes characteristic of Monk’s music are kind of softened all over their interpretation. But pay attention to the final chord on piano, that reminds us that it was a composition of Thelonious Monk.

That’s a lively, bouncing, swinging tune written by Thelonious Monk in winter 65/66. This take is from the 1968 recording Underground.

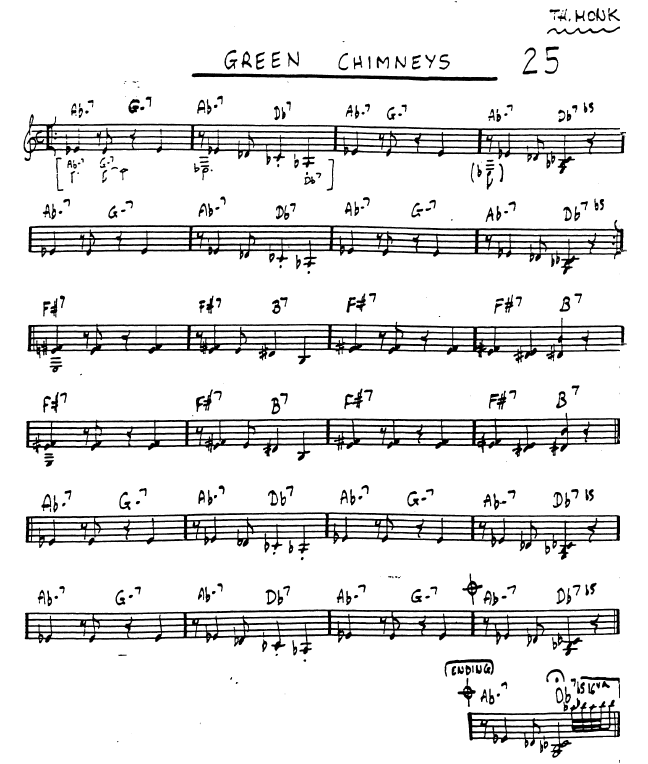

Thelonious Monk Quartet, Green Chimneys, 1968

This song was written in dedication to her children, especially Barbara (Boo Boo) who had been sent to a boarding school “Green Chimneys Farm for Little Folk” where children are taught in a farm setting, with many animals.

This 1968 version of the tune, that Monk apparently did not record many times, features Ben Riley on drum, Larry Gales on bass and Charlie Rouse on saxophone.

32 bars, AABA formThe melody is built on the repetition of a motive that spreads over two bars: four dotted quarter note figure followed by two quarter notes, so that every two note is in syncopation. This gives the tune a characteristic style (and is also reminiscent of claves in South-american music).

There are 2x8 bars of intro, first solo piano and then with the rhythm section. Then the sax tells the theme once and starts with 6 choruses. During the first one, you can hear Monk playing the melody, he will be play chords afterwards.

The chorus of Rouse is made of small phrases, there is a lot of space, and he uses either the rhythmic motive, or the melody. This never sounds as technical or difficult, but is always à propos.

At 05:25, Monk starts his two choruses by repeating twice the last phrase of the saxophone. At 6:46, it is not clear whether we hear a piano chorus or a bass chorus, but at 7:28, the piano stops and we have a bass chorus by Gales — Riley uses brushes.

At 05:25, Monk starts his two choruses by repeating twice the last phrase of the saxophone. At 6:46, it is not clear whether we hear a piano chorus or a bass chorus, but at 7:28, the piano stops and we have a bass chorus by Gales — Riley uses brushes.

The first two bass choruses have a very straight rhythm, quarter notes, a bit of syncopation and that’s it. However, at the third one, the drums stop and Gales explores more varied rhythms for one chorus. He will return to the bass walk for the last ones.

At 10:14, 3 drum choruses. Riley uses a great variety of sounds, toms, snare drum, rim shots, cymbals… Incredibly, he can make us hear the melody.

11:34, Monk and Rouse improvise jointly.

12:14 Back to the theme which ends in fermata, but you can hear that Gales is still playing notes on his bass!

Bill Frisell on electric guitar, Thomas Morgan on double bass. Recorded live, 2017.

Bill Frisell, Thomas Morgan, Epistrophy. 2017

Registered in 1941, Epistrophy is the first composition of Thelonious Monk, jointly written with the drummer Kenny Clarke (who supposedly found the theme by experimenting fingerings on ukulele!). It has an ABCA form, 32 bars.

As you can see on the score, parts A and B consist in a repetition of the same rhythmic motive— 4 eighth notes — starting at different places (every two bars, on the first beat, or on an eighth note later).

The melody of bars 1 and 2, resp 3 and 4 are transpositions while bars 3, 4 respond to bars 1, 2: the first three eighth notes are identical, but in bars 1, 2 it goes up (to the 6th of the chord) and in bars 3,4, it goes down (to a 2nd!)

Part C is interesting: it starts with a half rest (two beats), creating some tension. (The drummer I am is irresistibly tented to play two quarter notes on the bass drum. Those of bar 19 would respond to the two quarter notes of the melody on bar 18.)

Bill Frisell was one third of an incredibly trio, with Paul Motian on drums and Joe Lovano on saxophone. After Motian’s death in 2011, he founded another trio, with Thomas Morgan and Rudy Royston on drums. But he also published with Morgan two beautiful 2016 recordings (Small Town and Epistrophy).

One can find a version of Epistrophy in the recording of the same name, but it is not on YouTube, contrary to that live take I proposed. Listen how the musicians play with the melody. In the first bars, they understate part of it, as if everybody knew it, and dispatch it between guitar and bass.

To conclude this too long thread: Epistrophy is not an english word, but epistrophe is — it is the stylistic figure that consists in repeating something at the end of phrases.

Thelonious Monk, alone on Piano, from a 1970 French TV show.

His concentration, the intensity of his playing are astounishing.

Thelonious Monk, Crepuscule With Nellie, 1970

Nellie Monk was Monk’s wife. In many respects, she has been whom who made him stand upright. Who brought money to sustain the family when he was deprived of his musician’s card. Who collected money from promoters, paid musicians, made sure band members had airline tickets and even helped Monk get dressed. Who take care of him at Pannonica’s place when he seclused in silence until his death in 1982. She died in 2002.

He composed this tune in 1957 when she was undergoing surgery. AAB form, 24 bars, this is however the only tune by Monk which he played as it is written, without any improvised part. Either in this take (we have the tune twice), or in the recording ”Monk’s Music” where he plays it twice alone, and then twice with the reeds.

We had already listened to a few songs in which Monk shares his love for his family, and that one is magnificent above all. A song of devotion and love.

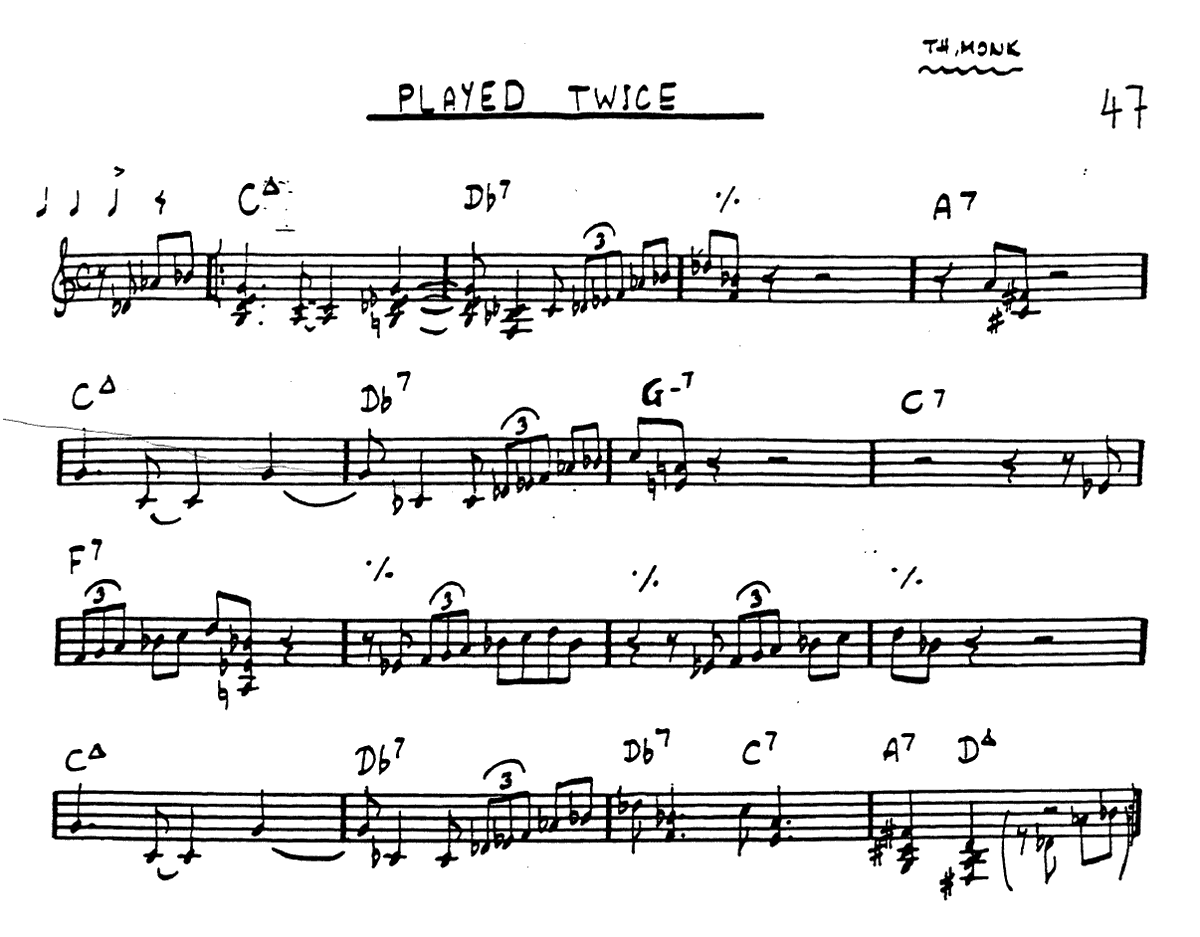

This is a 16-bar tune, AABA tune, built on essentially one motif that is repeated, displaced, transposed, plus another one, very short, which creates tension (on bars 1-2, 4-5 and 13-14).

The main motif is repeated 5 times. Even if you can’t read music, you can spot these “stairs” with a 3 on top, and observe that they start or land at different parts both vertically (different pitch) and horizontally (different time) of the bars.

In this 1993 interpretation, on can hear Brad Mehldau and Jorge (Jordi) Rossy who would later form 2 thirds of Brad Mehldau trio (with Larry Grenadier on bass). Mario Rossy — Jorge’s brother — si on bass and Perico Sambeat on alto saxophone.

Jordi Rossy, Brad Mehldau, Mario Rossy, Perico Sambeat, Played Twice, 1993

It starts with an exposition of the theme on the drums. The two beats on cymbal signal the last bar, and the theme starts again, spelt out by the saxophone who then embarks in a chorus (10, actually…). The tempo is very high, 256 bpm!

We then have 7 piano choruses, until (at 05:00) the musicians embark in trading eigths : 8 bars piano, 8 bars sax, 8 bars drums, but the musicians hide the starting and ending points of their improvisations, so it’s hard to keep track of the bars. In any case, I can’t.

At 06:02, the drummer takes 3 beautiful choruses, where he plays with melody and time (at some point he makes us believe he slows down, but he doesn’t, he just plays longer time values…). We finally have two more themes from the saxophone and it’s done.

This file stems out a Twitter thread, that was unthreaded day after day from February, 18, 2022 on. You can also get it on Markdown or PDF formats.

There is also a YouTube playlist that collects all of these recordings.